My Opinion | 129539 Views | Aug 14,2021

May 11 , 2025. By NAHOM AYELE ( FORTUNE STAFF WRITER )

The second phase of Addis Abeba’s redevelopment stretches across 132Km and affects over 2,800hct, touching myriad lives. With thousands of units handed over and many thousands yet to finalise contracts, the financial burden on residents is substantial. Payments beyond reach and looming deadlines leave many in a precarious balance, raising concerns about long-term social impacts. While seeking to empower through ownership, the underlying financial model places additional stress on families already stretched thin, reports NAHOM AYELE, Fortune Staff Writer.

Tsiriha Biru, 45, had never imagined that her rhythm of life in Adissu Gebeya, a northern Addis Abeba market hub she had known for three decades, could be broken in a single July afternoon. The mother of four paid less than 100 Br a year for a modest public (Kebele) house and counted on familiar neighbours.

Last summer, a city notice told her and 60 other families that the Addis Abeba’s riverside development project would "transform" their neighbourhood. Wereda officials offered two pathways. Stay in similar low-rent public housing or move into a government-built condominium with a sizable down payment. Tsiriha found the choice nothing but a dilemma.

“The houses for low-rent tenants were already occupied,” she recalled. “We're all pushed into condominiums, whether we like it or not.”

She has been living in a one-bedroom unit at Bole Arabsa Condominium Site 3 for seven months without a lease. Her only concern is a required prepayment of 120,000 Br, which is well beyond her means.

“I never wanted to move into a condominium,” she told Fortune.

She relies on what is left of the 85,000 Br the city paid her for transport costs and “emotional hardship.” The money is nearly gone, and a June 7 deadline looms.

“If I could borrow the rest, I’d pay,” she said. “If not, the street will be our home — me and my children.”

Stories like hers echo across the capital as the city authorities press for a redevelopment that is determined to overhaul Addis Abeba's identity. For many who support the project, the city is going through "a remarkable transformation;" for others, it is "losing its soul."

The corridor development project, as it is officially christened, was unveiled by the city administration in February last year. It set out to tear through dense neighbourhoods, replace ageing public rentals, mostly made of mud and tin roofs, with condominiums and re-engineer transport arteries that choke the capital each rush hour. Phase one ran 48Km through Piassa, Arat Kilo, Bole, Megenagna, Mexico and CMC areas, costing the city administration 33 billion Br. It relocated about 11,000 people.

The latest push to modernise the streets promised wide boulevards, better drainage and fresh housing blocks. But, it has also trapped thousands of its longtime residents in financial limbo.

Residents, many paying token rents under the public housing system, were told they could continue as low-cost tenants or buy a flat under the city’s mortgage program where the banks loan 80pc of the equity, after the balance is deposited upfront. In reality, say former tenants, the rentals were full, and officials pressed everyone toward buying condos that millions of low-income Addis Abebans barely imagine covering.

The second phase, now underway, is larger, stretching 132Km across 2,817hct, sweeping Casanchis, Aware and five other districts into the bulldozer’s path. Crowded lanes of sheet-metal shacks and mom-and-pop kiosks have given way to raw earth and half-poured pillars.

According to Tomas Debele, deputy director general of the Addis Abeba Housing Development Corporation, nearly 9,000 units — some for rent, most for sale — were handed over across both phases, but more than 4,000 households have yet to sign sales documents. The Corporation has imposed a deadline of June 7, 2025.

“The residents were given enough time,” Tomas said. “They're now obliged to sign the contract.”

If they fail, he warns, the Corporation may add interest charges on the Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (CBE) loans that financed construction and, in severe cases, repossess apartments.

“These houses were built using borrowed money from CBE through bond sales,” he said. “We expect to return up to two billion Birr from this. That's what is at stake.”

For many families, the sums look impossible. Tenants forced from kebele blocks received compensation, usually 85,000 Br for moving expenses and “emotional hardship.” Like Tsiriha, they have to raise an additional 120,000 Br to satisfy the 20pc deposit. The corridor program let families occupy flats before paying, a break from earlier condominium lotteries that required the advance first. What was intended as flexibility has turned into a mountain of unpaid balances and a second eviction threat.

No one feels that squeeze more sharply than Yitbarek Zegeye, 25, who lives in the same compound as Tsiriha in Bole Arabsa.

He remembers how swiftly the wreckers tore down his parents’ house near Shola, three days after the first notice. The shock triggered a health crisis for his mother, and much of the family’s payout went to hospital bills.

“She never fully recovered,” he told Fortune.

They chose a condominium, yet the required down payment now looks unreachable.

A similar story echoes a few blocks away.

During the project's first phase, Dawit Gebreyesus, a carpenter and father of three, was uprooted from Piassa’s Serategna Sefer. He rented near his old neighbourhood to make his children finish the school term, burning through his compensation. When he finally received keys to a unit in the same Bole Arabsa cluster, he found bare concrete walls, no wiring, plumbing or doors.

“I spent what little I had left to make it inhabitable,” he said.

His income, built on Piassa contacts, has fallen by half, and the sales contract for the condo remains unsigned.

Legal experts say aggrieved tenants have little leverage.

Yared Siyum, principal of Yared Siyum & Associates Law Office, noted that the Corporation still owns the flats without signed contracts.

“They retain full legal rights over the properties,” he said.

He advises families to pay if they can, though he believes the city should offer an administrative fix for those who cannot.

Under the scheme, buyers deposit one-fifth with the Addis Abeba Housing Corporation. The Corporation then transfers title deeds to Addis Abeba Land Development & Administration Bureau which then transfer it to CBE, which collects the remaining 80pc mortgage over up to two decades. Earlier programs barred families from entering flats without paying the first slice. Tomas says relocations under the corridor development are “a special case.”

However, experts who follow this development say the speed at which neighbourhoods are demolished and residents relocate demonstrates a campaign mentality rather than sound planning.

Anteneh Tesfaye, an architect and urban planner, believes corridor makeovers should have been planned over many years, with extensive consultations with residents who could be affected by the process.

“Individuals should have had the opportunity to choose housing options that suited their financial situation and personal preferences,” he said.

He argued that most relocatees are low-income; hence, they should share in the land value unlocked by redevelopment rather than shoulder the cost alone.

The strain is now visible at the biggest lender. CBE's President, Abie Sano, appeared before Parliament in March this year to report on third-quarter performance. He disclosed that the Bank had collected only 1.9pc of the 25.85 billion Br it projected from housing-bond repayments.

City leaders counter that Addis Abeba should modernise to keep pace with its swelling population, now close to five million, and a road network straining under twice-daily gridlock. They tout new asphalt, drainage culverts and landscaped medians already laid in Piassa and Mexico Square as proof that the upheaval will pay off. But critics say the social ledger is in the red.

To residents, development now resembles progress billed by the month, not a shared civic victory.

In the Bole Arabsa area, residents juggle incomplete infrastructure and rising bills. Water flows intermittently, elevators stall, and the absence of corner shops forces trips to distant markets. Dawit’s piece-work earnings have halved; Tsiriha hires a relative to watch her youngest child while she looks for cleaning jobs. Every Birr saved edges toward the deposit.

With the June deadline seven months away, the housing corporation has opened extra service windows and encouraged micro-finance lenders to offer small loans at interest rates above 15pc, terms many see as another trap. Anteneh recommended tapping the jump in land value to subsidise deposits.

“If you profit from their displacement,” he said, “you should also compensate them beyond a one-time allowance.”

The Mayor, Adanech Abiebie, pledged to push ahead.

“Addis Abeba cannot delay modernisation,” she told a recent city council session.

Tomas echoed that voice: “The houses are not free. People should understand that.”

At sunset, Tsiriha stood on her balcony and watched workers pour concrete for yet another block across a dusty field. She has taped the June notice to her wall next to a fading photograph of her old courtyard. Some nights she rehearsed phone calls to friends who might lend money; other nights she wondered where she would stretch a plastic sheet if officials locked the door.

“I've no room for hope,” she said, softly. “Just days on a calendar.”

Whether the corridor project ultimately eases traffic or fuels resentment may depend less on vehicle counts than on the fate of families like Tsiriha, Yitbarek, and Dawit, who find themselves paying the hidden price of Addis Abeba’s leap toward a shinier skyline.

PUBLISHED ON

May 11,2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1306]

My Opinion | 129539 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 125844 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 123855 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 121658 Views | Aug 07,2021

May 24 , 2025

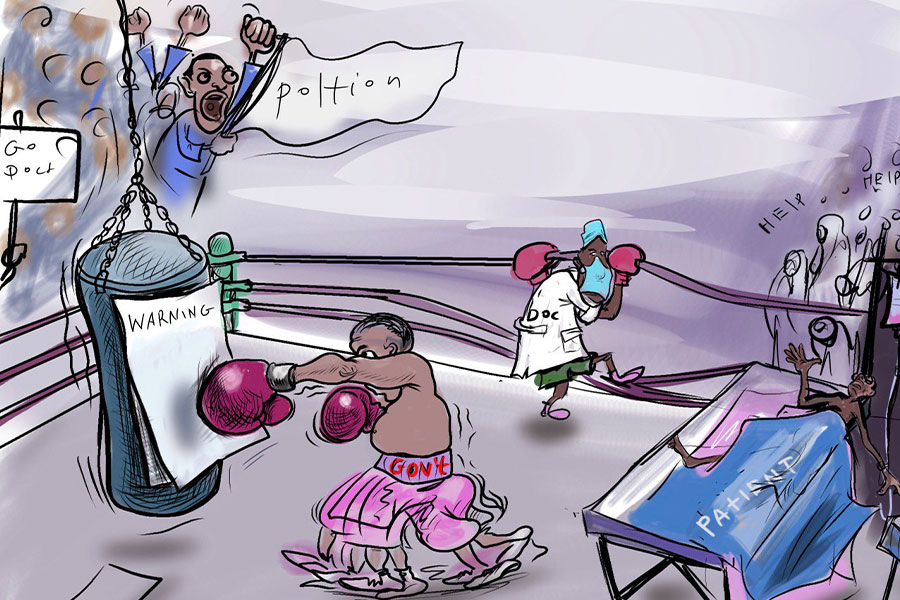

Public hospitals have fallen eerily quiet lately. Corridors once crowded with patient...

May 17 , 2025

Ethiopia pours more than three billion Birr a year into academic research, yet too mu...

May 10 , 2025

Federal legislators recently summoned Shiferaw Teklemariam (PhD), head of the Disaste...

May 3 , 2025

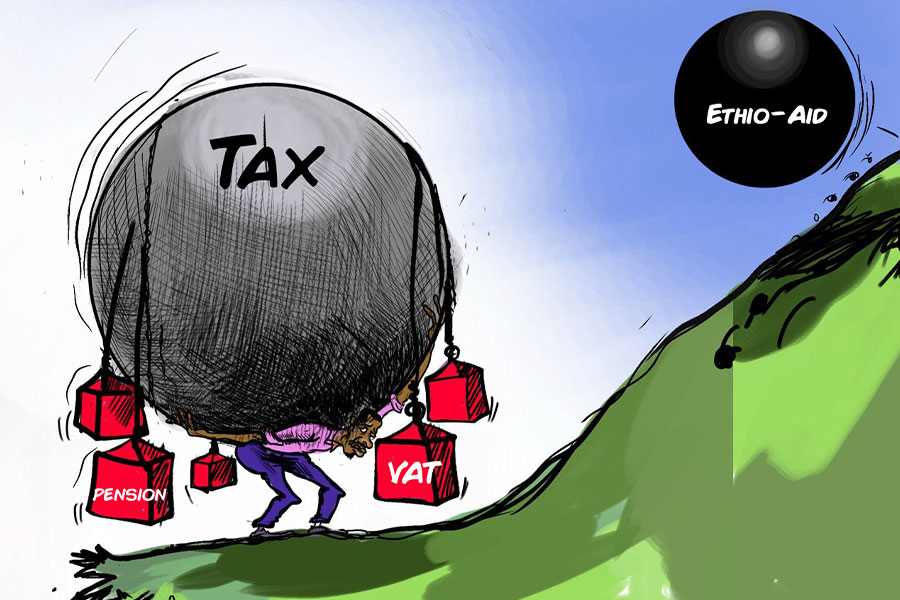

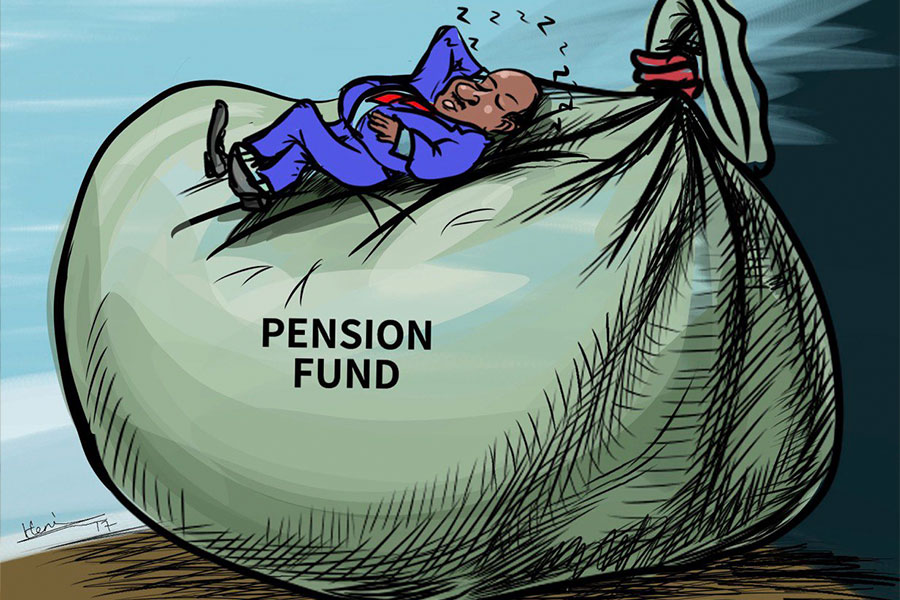

Pensioners have learned, rather painfully, the gulf between a figure on a passbook an...