Photo Gallery | 156907 Views | May 06,2019

Sep 6 , 2025. By Keun Lee ( a former vice chair of the National Economic Advisory Council for the President of South Korea, is a professor of economics at Seoul National University. )

Financialisation, the growing influence of financial markets and shareholder value over corporate strategy, differs from financial development, which expands access to credit and financial services. In this commentary provided by Project Syndicate (PS), Keun Lee, a professor of economics at Seoul National University, argues that while innovation and financial development can boost growth and jobs, unchecked financialisation may quietly reshape the social contract in advanced and emerging economies alike.

Over a decade ago, Nobel laureates Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, together with their co-author Thierry Verdier, contrasted America's "cutthroat" brand of capitalism with Western Europe's "cuddly" version. The qualities that make cutthroat capitalism more conducive to innovation, they argued, also lead to higher levels of inequality, while cuddly reward structures tend to lead to lower growth and higher welfare. Today, inequality is soaring, notably in the United States.

Do policies aimed at boosting innovation risk make a bad situation worse?

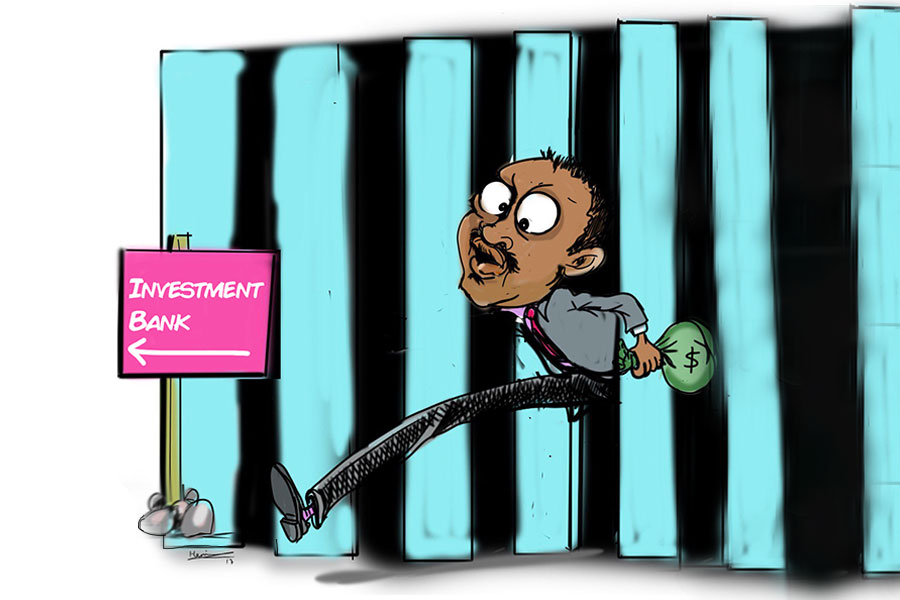

In the economics literature, one can find plenty of support for the idea that technological innovation is a key driver of inequality. But another important line of thinking attributes rising inequality largely to "financialisation," a term that encompasses the financial sector's growing share in the economy, the increasing reliance of non-financial firms on financial activities as a revenue source, and corporate governance focused on maximising dividends for shareholders, rather than investing in future growth.

My co-author Juneyoung Lee and I recently sought to shed light on which factor has a greater role in driving inequality. We grouped countries according to their levels of innovation and financialisation. We found the highest levels of inequality in the low-innovation and high-financialisation group, which includes a range of developed and emerging economies, such as Brazil, Spain, and Turkey. Inequality was also relatively high in the group where both innovation and financialisation were substantial, including most of the Anglo-American capitalist economies, as well as Japan and South Korea.

By contrast, the high-innovation and low-financialisation group, which includes many of Europe's advanced economies, such as Austria, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, and Norway, showed the lowest levels of inequality. The low-innovation and low-financialisation group, which includes most of the emerging economies, such as India, Russia, and some Eastern European countries, has intermediate levels of inequality.

Ultimately, we found no link between innovation and income inequality. This finding challenges those of the French economist Phillippe Aghion, who argues that innovation, as measured by the quality-weighted number of patents, tends to exacerbate inequality, because the profits generated by the associated productivity gains become monopoly rents for the innovators. But, Aghion's approach fails to account for other effects of innovation, such as increased investment in physical capital, which can mitigate negative distributional effects by creating job opportunities and increasing the incomes of workers who work with the new systems or equipment.

These benefits are particularly robust when it comes to "product innovation" (the introduction of a new or updated good), because the new product generates a wave of new demand, which spurs increased investment. "Process innovation" (the introduction of a new method of production) is often labour-saving in the short run, but even here, the effect on inequality is typically offset in the longer term by cost savings.

Using the same measure of innovation as Aghion, but accounting for these factors, I have found that innovation does not affect overall inequality or the income share of the top one to five percent. The monopoly rents associated with innovations tend to be short-lived, as other firms eventually adopt the new technology.

This brings us back to financialisation, which is directly correlated with inequality, specifically, the gutting of the middle class. As the ratio of stock-market capitalisation, or of stocks traded, to GDP rises, income is redistributed from the middle class to top earners. (The incomes of the bottom 50pc are not necessarily affected.)

This effect could be seen in the US after the 2008 global financial crisis, when unprecedented monetary easing caused stock prices to rise, giving the illusion of a robust recovery, even as employment lagged and the real economy struggled. Similarly, in the third quarter of 2023, Japanese stock prices surged to record highs, owing to monetary easing and share buybacks, even though growth had been negative for the previous two quarters.

It is worth noting that financialisation (the influence of financial activities on non-financial firms) is not the same as financial development (the depth, accessibility, and capabilities of financial institutions). Financial development, measured as the ratio of private credit, or of liquid liabilities, to GDP, does not appear to have a significant effect on the income share held by the highest earners.

The message is clear. Policymakers concerned about inequality should not fear technological innovation or financial development, which will lead to growth and jobs in the long run. But they should consider steps to mitigate the distributional consequences of financialisation, such as raising taxes on the financial incomes of the wealthiest households. If they do nothing, the decline of the middle class will continue.

PUBLISHED ON

Sep 06,2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1323]

Photo Gallery | 156907 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 147198 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 135766 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 135287 Views | Aug 14,2021

Sep 13 , 2025

At its launch in Nairobi two years ago, the Africa Climate Summit was billed as the f...

Sep 6 , 2025

The dawn of a new year is more than a simple turning of the calendar. It is a moment...

Aug 30 , 2025

For Germans, Otto von Bismarck is first remembered as the architect of a unified nati...

Aug 23 , 2025

Banks have a new obsession. After decades chasing deposits and, more recently, digita...