My Opinion | 130627 Views | Aug 14,2021

Jun 8 , 2025. By RUTH BERHANU ( FORTUNE STAFF WRITER )

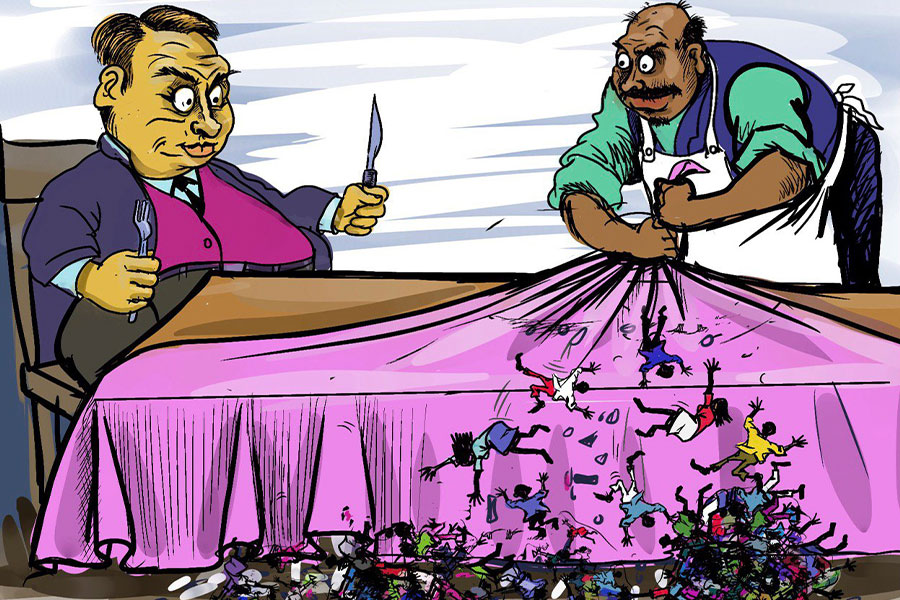

With only 28pc of Ethiopian women having access to the necessary sanitary products, many resort to makeshift solutions. Policies intended to alleviate financial burdens do not always translate to savings for the consumer, as seen with the persistent value-added tax on menstrual products. The disconnect between policy and reality is evident, reports Ruth Berhanu, Fortune Staff Writer

Meseret Mulle rises before dawn in the crowded quarter around Golagol Tower, waking her two sons, aged 13 and eight, in the single “kebele” house they share. At 35, she cleans homes in Gerji, a two-hour walk each way when she cannot spare the fare.

Her monthly wage is about 4,000 birr, or roughly 30 dollars at last week's exchange rate by the Central Bank, and 450 Br a month of that vanishes on transport, even though she often makes the boys walk beside her and pays only for the taxi ride home. The hidden cost is invisible. Meseret bleeds heavily regularly, sometimes going through four packs of sanitary pads.

“It is a constant worry," she told Fortune. "How will I manage today? The bleeding never stops. I can’t afford the pads I desperately need.”

A 500 Br stipend from Bole District Wereda 04’s Women & Social Affairs office lasts less than a week. The rest comes from friends, credit at neighbourhood kiosks and rags at night.

Her dilemma sits at the intersection of a quiet but widening “period-poverty” divide, where the price of managing menstruation often eclipses rent, milk or schoolbooks. Only 28pc of Ethiopian women say they have everything required to manage their monthly cycle, according to the Performance Monitoring & Accountability 2020 survey. A quarter use nothing designed for the task, substituting rags, newspaper or even cloth stuffed with ash.

Pads and tampons carry 15pc value-added tax (VAT), and although import duties on finished pads fell to 15pc and the 10pc surtax vanished in 2022, a directive from the Ministry of Finance in June last year granting VAT holidays on basic goods left menstrual products off the list.

The mismatch between tax policy and lived reality is clear to Kaleab Getaneh, co-founder of "Mela for Her," a social enterprise in Addis Abeba that began selling reusable "MELA Pads" in 2019 and secured full registration by March 2020. The MELA Basic, Premium, and Eco lines are pitched as eco-friendly and long-lasting, but production costs have far outpaced their price tags. Imported fabric now costs seven dollars to 10 dollars a kilogram; plastic snaps cost about seven-tenths of a U.S. cent each; sewing thread is 50 cents a roll.

Local fabric prices have jumped 95pc in the last three years and 60pc in the two years. An increase of roughly 35pc pushed administrative overhead more than 50pc higher; electricity bills have quadrupled; fuel inflation is felt on every truck. However, MELA Basic jumped only to 300 Br from 190 Br in 2001, and MELA Premium climbed to 405 Br from 300 Br, a respective gain of 57.9pc and 35pc.

Mulunesh Weldemariam feels the pressure of the price each payday. The 45-year-old janitor at Haddis Alemayehu Secondary School, on Mickey Leland Street, earns 3,000 Br a month, while her husband works nights as a security guard. Rents in Bole Arabsa, Lemi Kura District, consume a substantial portion of their income. Milk for their year-old son comes next. A single pack of pads costs 75 Br.

“I prioritise my daughter’s needs over my own,” she said of her 17-year-old. “Sometimes, I buy pads for her. However, I use sheets. It’s hard, but what can I do?”

Supply shocks also ripple through the private sector. Ruby, a pad brand launched in mid-2023 by two businesspeople, imports finished goods from Jackson Care Product in Jaipur, India. Ashenafi Zemichael, a shareholder, lists a 35pc import tariff, costlier raw materials, higher shipping rates and compliance fees that drag on every box.

“Despite these difficulties, Ruby remains committed to providing high-quality products at affordable prices," he told Fortune. "It's actively working with partners and regulatory bodies to address these challenges effectively.”

A tax-policy chief at the Ministry of Finance, Mulay Weldu, argues that while cotton cannot receive a carve-out for one item, inputs for pad production already pass duty-free. Yet, officials concede that relief rarely reaches consumers.

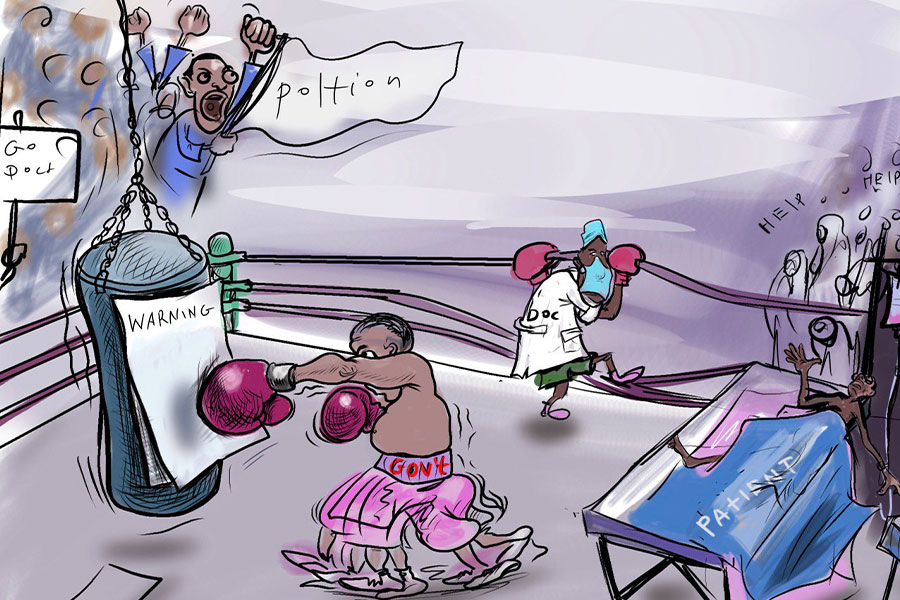

Bezuwerk Atile, deputy principal of Fitawurari Habte Giyorgis No. 2 Primary School in Addis Ketema District, watches the fallout daily. More than 30 girls rely on the school for pads, but there is no dedicated budget allocated for this purpose. The medical-supplies line buys only a single pack of 10 pieces each month. No less than 10 students come to her office every day.

“We give a few pads from the pack, never the whole pack," she said. "Female teachers chip in from their own because we don’t want the girls to miss class.”

Policymakers are trying to ease the squeeze, lest they have paid attention to the problem. Raw-material duties for pad factories dropped to 10pc from 30pc, yet shelf prices still climb. According to Zekariyas Desalegn, a gender-based violence specialist at the Ministry of Women & Social Affairs, they plan a letter-of-guarantee system where a manufacturer requests duty-free status for specified inputs. The Ministry verifies the order, and the Finance Ministry authorises duty-free tax imports.

Parallel talks with the Ministry of Trade & Regional Integration (MoTRI) target wholesalers who hoard pads for price spikes. A high-level meeting set for next month could classify pads as urgently needed medical supplies, obliging importers to seek special permits and, potentially, sell through pharmacies or hospitals.

Officials hope a new association of washable-pad makers, backed by a finance, awareness, distribution and manufacturing task force under the Ministry of Women & Social Affairs, can expand domestic output. Currently, the industry is relatively thin. Rising material costs and slim margins have driven several factories out of business, a problem the committee wants to identify and address.

For many advocates, these efforts are only a beginning, not an end.

Urji Biso, a law lecturer at Haramaya University and project coordinator at the Ethiopian Women Human Rights Defenders Network, believes cutting taxes is only one lever.

“The high cost of sanitary pads is a major driver of period poverty among low-income households,” she told Fortune.

Urji links unaffordable pads to school absenteeism, lost wages, poor hygiene and mental strain. Scaling local production, normalising washable pads where clean water is available and teaching reproductive health in classrooms are equally urgent.

“Access to sanitary pads is tied to reproductive health and rights,” she said.

She pointed to neighbouring Kenya, which scrapped the pad taxes and distributes them for free in schools. Subsidies could ensure “all women and girls, regardless of economic status,” can manage their periods safely.

Inside homes like Meseret’s, the policies remain abstract until prices fall. She stocks one or two packs at a time, rationing each pad by the hour. When bleeding intensifies, she doubles up or improvises with strips torn from sheets. Friends quietly hand over extra packs when they can. Storekeepers extend credit they suspect will never be repaid. She has visited clinics, but tests and treatment lie far beyond her means.

PUBLISHED ON

Jun 08,2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1311]

My Opinion | 130627 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 126941 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 124945 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 122646 Views | Aug 07,2021

Jun 7 , 2025

Few promises shine brighter in Addis Abeba than the pledge of a roof for every family...

May 31 , 2025

It is seldom flattering to be bracketed with North Korea and Myanmar. Ironically, Eth...

May 24 , 2025

Public hospitals have fallen eerily quiet lately. Corridors once crowded with patient...

May 17 , 2025

Ethiopia pours more than three billion Birr a year into academic research, yet too mu...