My Opinion | 130627 Views | Aug 14,2021

Jun 7 , 2025.

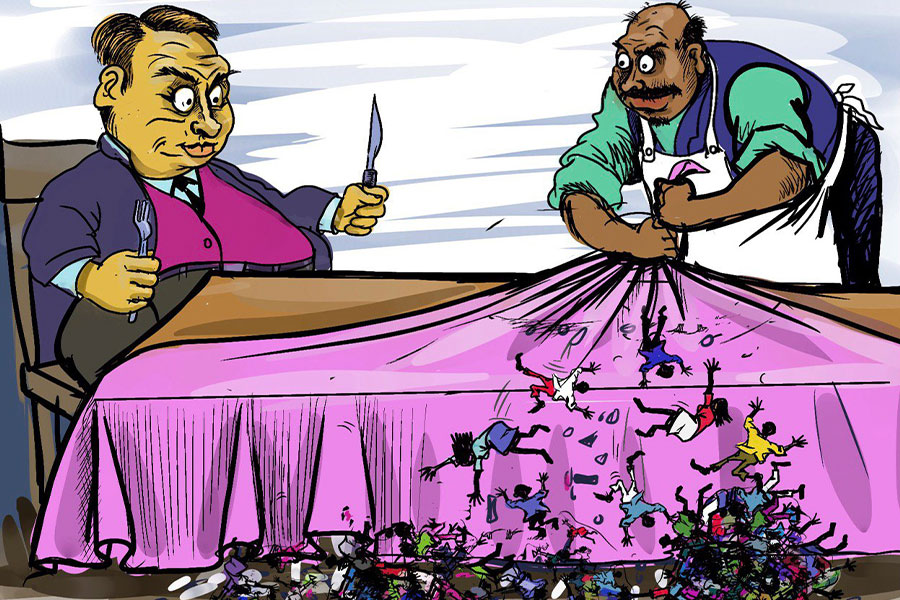

Few promises shine brighter in Addis Abeba than the pledge of a roof for every family. Gleaming office blocks now punctuate horizons once defined by tin-roof shacks, yet the capital’s housing gap keeps widening.

More than five million people, according to the city administration’s official projection, reside in the city, and a growing share live in informal dwellings.

Officials insist relief is coming, but the latest scheme, a headline-grabbing pledge of 120 billion Br from the state-owned Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (CBE) to finance homes for members of the public service, with teachers first in line, risks repeating an old pattern. Grand announcements that collapse under arithmetic.

The plan’s optics were striking. Abie Sano, CBE’s president, stood beside Kidist Woldegiorgis, who runs the city’s Housing Development & Administration Bureau, to unveil a memorandum promising cheap mortgages and “affordable housing” that would “uplift public servants.”

However, beneath the fanfare, the sums tell a harsher tale. The cost-sharing formula assumes buyers put down one-quarter of the price while lenders and subsidies cover the balance. On that basis, the CBE would bankroll 75pc of the construction for about 30,000 units, each costing roughly four million Birr.

A prospective buyer should therefore raise one million Birr upfront. This alone bars most teachers, who take home barely 10,000 Br a month. Even if they somehow scrape together the deposit, equivalent to about eight years of untouched salary, the remaining mortgage is still punishing. At a 14pc rate over 20 years, monthly repayments top 35,500 Br, more than triple a typical teacher’s income.

The gulf between pay cheques and payment transforms a supposed lifeline into a mirage.

Such disconnects are not new. Successive leaders, from Mengistu Hailemariam (Col.) to Meles Zenawi and Hailemariam Desalegn, have long tried to marry ambitious public housing projects with modest fiscal means. What is new is the scale of the problem.

Population growth, rapid urbanisation, double-digit inflation, and a weakening Birr have deepened pressures on shelter. Last year, consumer prices rose above 30pc and the market value of the Birr against the dollar slid by over 140pc since mid-last year.

Depressingly, public-sector wages barely moved. For many civil servants, housing already devours more than half of their earnings. They now face billion-Birr promises they cannot use.

Informal builders have always been on the sidelines. Across Africa, more than 70pc of new housing is erected outside formal systems, and Addis Abeba fits the rule. Rotating savings groups, such as “Equb,” remittances, and hand-to-hand loans, finance incremental construction.

The process is often opaque and expensive, yet it is faster and more responsive than formal credit channels. More than 800,000 people are on a waiting list for city-run flats, some of whom have been waiting for over a decade. Private developers, meanwhile, court the wealthy with units starting at 10 million Birr, placing even dual-income households beyond reach.

Mortgage systems are thin, and small interest-rate moves lock out swathes of buyers. The authorities’ pinning their hopes on commercial loans to fix a structural shortage is thus doubly perilous.

Other countries offer hints of what might help, drawing from two key ingredients: realistic financing and deliberate inclusion.

The state could target the hardest barrier, which is the down payment. A housing equity fund, financed by urban development bonds or concessional loans from partners such as the World Bank or the African Development Bank (AfDB), could provide deposits for teachers, nurses, and members of law enforcement.

Interest-rate subsidies or public guarantees could halve borrowing costs. At six percent over 20 years, monthly payments on a three million Birr loan drop to about 21,500 Br, still steep, but less ruinous than 35,500 Br. Policy should nurture cooperative housing and rent-to-own models that convert rent into equity over time, easing entry into ownership.

Developers, too, need incentives. Density bonuses, swift permitting, tax holidays, and grants of public land could coax firms to build below set price ceilings. Well-designed carrots cost money; nonetheless, they can be cheaper than the social cost of overcrowded slums and festering discontent.

Without them, the formal market will continue to target the tiny slice of households that can pay cash.

Any solution should also take into account land, which is scarce inside Addis Abeba’s city centre but plentiful on its outskirts. Transparent auctions, digitised registries, and predictable zoning rules would curb speculation and cut costs.

Yet money and maps alone will not suffice to address the housing policy, which straddles fiscal and monetary realms. The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) has juggled currency weakness and inflation; its cautious loosening this year offers space to align home-loan rates with social objectives.

But prudence is vital to avoid the likely situation where subsidised credit swells a new bubble. A coordinated push, combining cheaper finance, land reform, and incentives for builders, would be bolder than any single billion-Birr pledge.

With Addis Abeba growing by about four percent a year, the risk of inaction is mounting. The city’s dualism — formal aspiration against informal reality — grows starker. Commercial lending cannot bridge such a structural chasm. Each delay entrenches informal sprawl, strains water and power networks, and leaves newcomers in ever more precarious shelters.

Addis Abeba does not lack land, labour or demand. It lacks a housing finance system tailored to its social objectives.

City officials should be more aware of this. Although Kidist insisted the loans were “free from excessive interest charges,” the data reveal otherwise. A scheme that sets entry costs at eight years' salary and monthly repayments at three times the income is not generous; it is exclusion dressed as inclusion.

Until it is redesigned, her scheme will deepen frustration among the very workers she pledged to reward.

Housing matters far more than shelter. It anchors families, encourages mobility, and buffers inflation. In a country where the cost of living is rising and public wages are either stagnant or lagging, access to a modest flat signals dignity and a stake in the city. When that promise fails, trust frays.

Finance Minister Ahmed Shedie and Central Bank Governor Mamo Mihretu can still salvage their administration’s credibility by matching policy with arithmetic. That means scrapping symbolic mortgages and embracing more demanding tasks, such as lowering rates, backing cooperatives, and compelling developers to build more affordably.

Other countries have shown that careful design, aided by technology and fiscal discipline, can bring homes within the reach of millions. Ethiopia’s contemporary leaders can learn from them.

The alternative appears clear. Waitlists that stretch past a million names, informal settlements that sprawl, and a middle class priced out of its capital. To build houses, the state should first create a system that works for its people. And trust, like shelter, is laid brick by brick, never by a memorandum of understanding.

PUBLISHED ON

Jun 07,2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1310]

My Opinion | 130627 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 126941 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 124945 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 122646 Views | Aug 07,2021

Jun 7 , 2025

Few promises shine brighter in Addis Abeba than the pledge of a roof for every family...

May 31 , 2025

It is seldom flattering to be bracketed with North Korea and Myanmar. Ironically, Eth...

May 24 , 2025

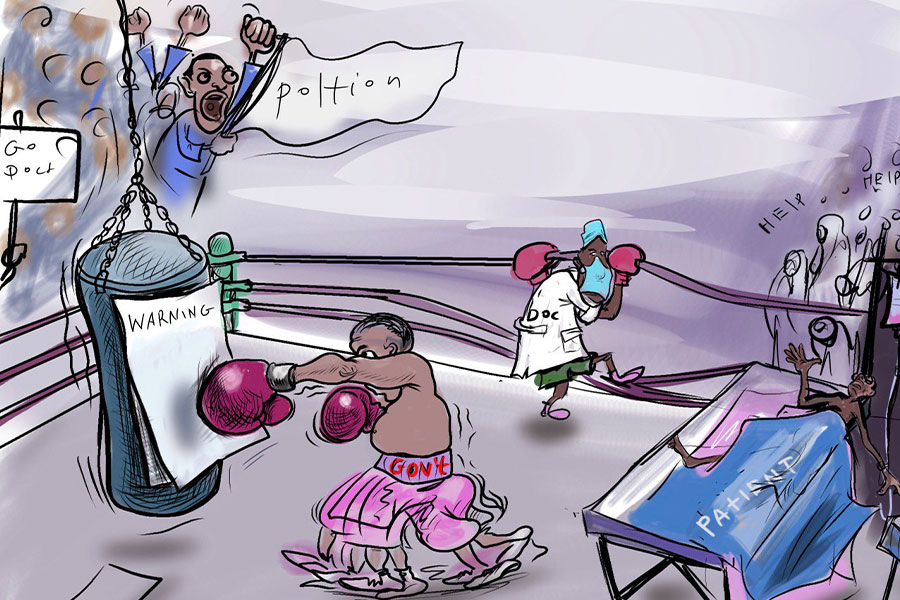

Public hospitals have fallen eerily quiet lately. Corridors once crowded with patient...

May 17 , 2025

Ethiopia pours more than three billion Birr a year into academic research, yet too mu...