My Opinion | 130803 Views | Aug 14,2021

Jun 15 , 2025. By ZELALEM GIRMA ( FORTUNE STAFF WRITER )

Hana Surafel, a determined 29-year-old mother of three, transformed her dream of opening a bakery in Gulele, near Addisu Gebeya, into a reality. With a background of selling traditional fabrics at Merkato, Hana aspired for a new beginning. Her journey took a turn when a taxi ride introduced her to Telebirr's no-collateral loans, unlocking new avenues of opportunity. By leveraging digital credit, she now provides fresh bread to her neighbours, sustaining her family's financial needs, reports Zelalem Girma, Fortune Staff Writer.

Hana Surafel spent years behind the counter of her uncle’s traditional cloth stall in Merkato, listening to customers haggle over fabric patterns. The 29-year-old mother of three earned a "respectable wage," yet each long day ended with the same unfulfilled wish. She was adamant to open a neighbourhood bakery in Gulele, near Addisu Gebeya, where the scent of fresh bread would rise with the morning sun.

Lacking a property, a vehicle, or any other conventional collateral, she relegated the dream to quiet evening conversations. That is, until a taxi ride to work changed her fortunes.

A radio spot crackled through the minibus speakers, advertising no-collateral loans available through Telebirr, the mobile-money arm of the state-run Ethio telecom. Hana pulled out her phone, curious. Within weeks, she was seated inside a branch of the Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (CBE). Four months later, she received word that a 50,000 Br loan had been approved and automatically linked to her Telebirr wallet and CBE account.

Adding the funds to savings of 85,000 Br, she scraped together 135,000 Br and rented a cramped storefront a few steps from her front door. Last week, her ovens fired before dawn, supplying crusty rolls to a growing queue of neighbours.

“Access to finance used to be for those who already had something,” she said as trays cooled on a wooden rack. “Even someone like me can open a business and stand on her own with digital tools like Telebirr.”

Sales are strong enough to cover family expenses and monthly debt payments.

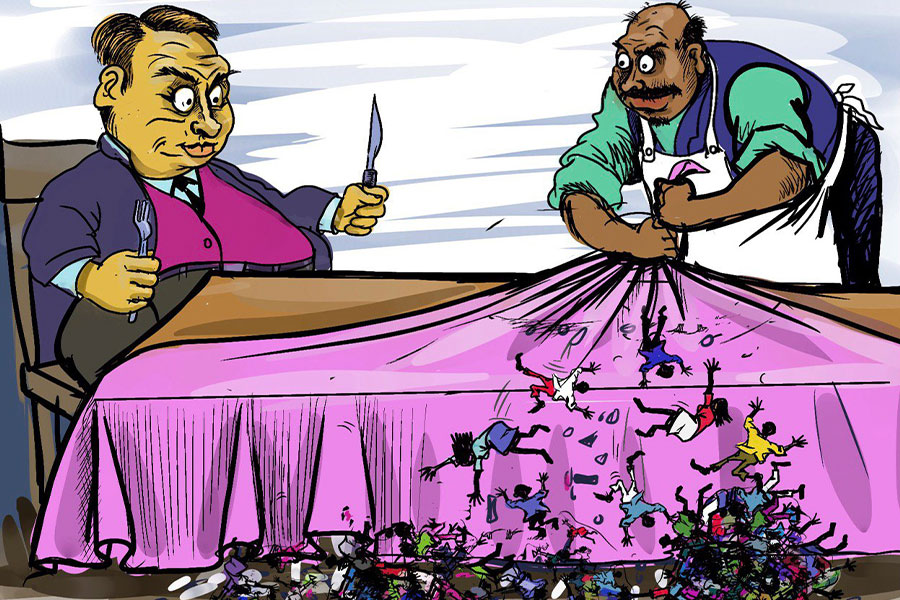

Phone-based credit is reshaping the financial ecosystem, where more than 80pc of adults still live outside the formal banking system.

Hana is one of the roughly 95pc of borrowers who repay on schedule. The same technology that helps individuals like Hana, however, is producing cautionary tales. Defaulters face steeper consequences.

“If the amount is not settled within the agreed period, the case may proceed to court,” said Tamiru Taba, a customer-service officer at Telebirr. "The service is inclusive but also makes clients accountable.”

Company officials confirm the platform can block services for delinquent borrowers.

Bayush Ejara, a mobile-money specialist at Telebirr, described the platform as a “financial marketplace” that enables rural and urban clients to borrow and save without visiting a branch.

“We’re shifting from asset-based lending to opportunity-based inclusion," Bayush said.

Transaction patterns, including frequent transfers, steady digital deposits, and verification through the national ID database, primarily determine eligibility.

However, the twin impulses — widening credit while enforcing repayment — are animating a wave of digital lending partnerships between telecom operators and commercial banks. Telebirr has struck deals with CBE, Dashen, and Siinqee banks alone.

Telebirr offers two loan products in partnership with the CBE. The first, "Enderas", targets short-term cash gaps. Borrowers can take between 100 Br and 4,000 Br for no less than 10 days at a 1.25pc facilitation fee; up to 10,000 Br for 25 days at 2.5pc; or as much as 15,000 Br for 60 days at 6.5pc. The second product, "Adrash," caters to salaried workers whose paychecks flow through Telebirr. Customers may tap up to 600,000 Br, capped at 25pc of their monthly income for one month at a four percent fee, with repayments stretching over four months of salary repayable over a year.

Siinqee Bank, one of the lenders that spun out of the micro-finance industry, integrates its “Wabi” micro-credit window with Telebirr. Loans range from 100 Br for five days to 30,000 Br for 45 days. Employees whose wages pass through Siinqee may borrow the equivalent of five months’ pay, from 1,000 Br to one million Birr, and settle over 14 months.

Dashen Bank offers its "Mela" and "Mela Medaresha" lines through Telebirr, with sums from 100 Br to 36,000 Br on daily, weekly, or monthly cycles. Facilitation fees run between one percent and 10pc; late payers incur daily penalties of 0.11pc to 0.5pc.

An outlier to this trend is the Bank of Abyssinia (BoA), which pursues a branch-free strategy. Its digital platform, also available on a mobile app, Apollo is a standalone platform marketed to the diaspora and urbanites weary of paperwork.

Its director for digital customers, Abay Sime, likens Apollo to “a full bank in your pocket.” Prospective borrowers are required to upload an ID, a selfie, and a recent transaction history. The app conducts a liveliness test to verify that the applicant is human. Behind the screen, a credit-scoring model ranks risk, enabling disbursements deemed “high-risk but manageable.” Until last week, the Bank had issued, through Apollo, 2.2 billion Br to more than 60,000 users.

“Our biggest job is awareness,” Abay told Fortune. “We constantly remind clients not to violate the rules.”

The Cooperative Bank of Oromia (Coop Bank) entered the arena two years ago with "Michu," a suite of products designed for business people who have been shut out of collateral-based lending. Ashenafi Abate, who heads the platform, divides Michu into three channels. Michu Wabi serves micro-sized firms that require 50,000 Br to 100,000 Br at an eight per cent interest rate and fees. Michu Guya caters to informal traders and street vendors known as "gulit," who are not required to produce business licenses, advancing 5,000 Br to 15,000 Br for a seven-day period. Michu Kiyya focuses on women, advancing up to 30,000 Br at a 3.5pc rate.

“It’s our way of supporting women who are making a tangible impact,” said Ashenafi.

Coop Bank’s digital push has opened 1.5 million accounts, of which women hold 1.1 million. Loans totalling 25 billion Br have coursed through Michu, and women have secured 7.9 billion Br, evidence, Ashenafi says, of an intent to “include previously marginalised groups.” He finds repayment to be “commendable,” though clients who drift into arrears receive text nudges before legal steps are taken.

Ethiopia’s leap into mobile credit mirrors a broader African trend. In Kenya, Safaricom’s M-Pesa began parcelling out phone-based microloans more than a decade ago, spawning a cottage industry of fintech apps. Regulators in Addis Abeba watched warily until 2021, when officials granted Telebirr a license to operate under the telecom monopoly. Private competitors are now lobbying for entry, a shift that could drive rates lower and encourage banks to offer larger, unsecured products.

For lenders, the attraction is data. Phone records, digital payments, and geo-location trails provide near-real-time insights into a borrower’s cash flow, enabling credit algorithms to replace land titles or car deeds as collateral proxies. For borrowers, the pitch is speed. Applications that once required days of queuing and notarised documents can be approved in minutes. That convenience, however, comes with a different form of leverage. A handset can be switched off, or a wallet can freeze at the first missed payment.

According to economists, the fledgling credit-scoring regimes remain opaque. They warn that if the model overestimates repayment ability, defaults will climb quickly. Telebirr insists that its repayment success rate demonstrates the effectiveness of the screening process, but critics note that the loans are still relatively small. The real test, they say, will come when platforms push farther into higher ticket sizes like Adrash’s 600,000 Br ceiling.

Clients like Hana have little time for debates about risk models. Hana slips on plastic gloves each evening, kneads dough, and arranges loaves for predawn baking. Her three children, once crowded into the back of her uncle’s shop after school, now sweep crumbs off the bakery floor while homework waits.

PUBLISHED ON

Jun 15,2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1312]

My Opinion | 130803 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 127142 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 125136 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 122814 Views | Aug 07,2021

Jun 14 , 2025

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars...

Jun 7 , 2025

Few promises shine brighter in Addis Abeba than the pledge of a roof for every family...

May 31 , 2025

It is seldom flattering to be bracketed with North Korea and Myanmar. Ironically, Eth...

May 24 , 2025

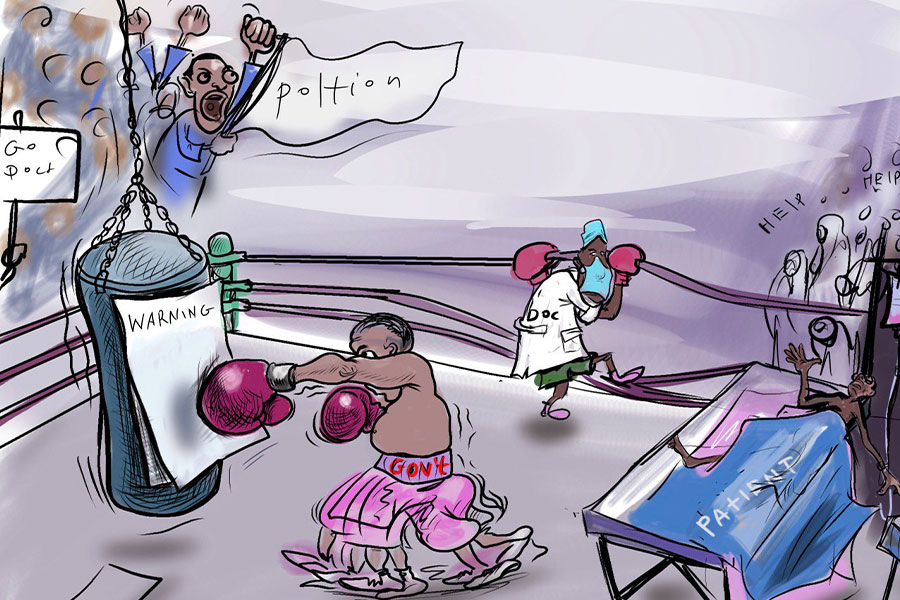

Public hospitals have fallen eerily quiet lately. Corridors once crowded with patient...