My Opinion | 133429 Views | Aug 14,2021

Jun 14 , 2025.

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars almost every other decade in nearly 70 years, now hears a rising chorus of turmoil.

Ethiopia’s leaders have become vocal, arguing that a country with more than 100 million people and one of the continent’s largest economies cannot remain in what they call a “prisoner of geography”. They promise to secure a direct corridor to the Red Sea and warn that, if negotiations stall, “all options are on the table”.

Landlocked states are no rarity, though. The world counts 44, no less than 16 of them in Africa. Ironically, three are still fighting for recognition, while Liechtenstein in Europe and Uzbekistan in Asia are doubly landlocked, surrounded by neighbours with no coast of their own. Only Kazakhstan, Austria, and Switzerland post GDP output close to or above the 200-billion-dollar mark.

None, however, faces Ethiopia’s peculiar handicap. A population above 100 million and a GDP projected to reach 174.34 billion dollars this year and 186.37 billion dollars in 2026. No other landlocked country suffers from such double jeopardy as Ethiopia.

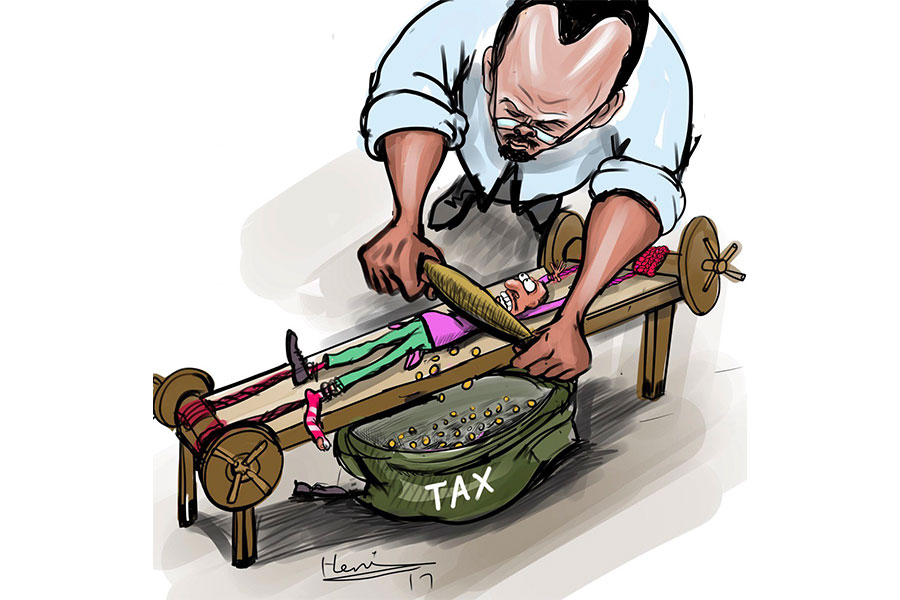

The economic penalty for having no shoreline is understandably steep. World Bank models put freight costs for African landlocked countries 50pc to 75pc higher than those for their coastal peers. Ethiopia is estimated to lose as much as two billion dollars a year in logistics fees, most of which are paid to Djibouti, whose ports handle nearly every inbound and outbound container.

Small wonder Ethiopia’s contemporary leaders are determined to have a fresh route to salt water.

Nonetheless, numbers do not create entitlement. The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea allows landlocked states transit rights only “on terms to be agreed”. The 1965 Convention on Transit Trade of Land-Locked States hammers home the same idea. Article 2(4) of the UN Charter forbids threats or the use of force against another state’s territorial integrity. Population size, GDP, and geographic breadth appear nowhere to be found in that text.

Neighbours are unsurprisingly twitchy. Eritrea’s long-serving autocrat, Isaias Afwerki, has slipped into marathon interviews, accusing Ethiopian leaders of acting as proxies for foreign conspirators. Djibouti and Somalia rushed to denounce the memorandum that Ethiopia signed with Somaliland last year. The phrase “all options are on the table” travels fast, and not only in diplomatic cables.

The Ethiopian leaders’ messaging does not seem to provide much reassurance.

Foreign Minister Gedion Timotheos (PhD) insisted that “Ethiopia is not in a war of words with Eritrea”. However, other civilian and military officials brand Eritrea a “historical enemy” and boast of shifting policy “from defensive to offensive”. Dina Mufti, a former Foreign Ministry spokesman and a member of the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, blamed “Eritrean provocation”.

The result is confusion abroad and mistrust in Asmara, where many suspect polite talk masks worrisome plans.

Casting sea access as a “natural right” invites a zero-sum interpretation. It erodes the diplomatic standing Addis Abeba craves. In a region still haunted by fresh memories of brutal war, swagger is a poor negotiating tool.

Sadly, the broader geopolitical landscape is no steadier. The Horn of Africa is already trapped in overlapping conflicts, political fragmentation, and humanitarian catastrophe. Governance structures creak under militarised survival tactics and elite feuds. What once looked like sporadic turbulence is turning into a chronic disorder.

External meddling has become an industry in its own right. China courts the region with its Belt & Road railways, loans and a naval base in Djibouti. The United States wants the shipping lanes kept open but, wary of new entanglements, has subcontracted strands of security policy to the Gulf states. Israel, buoyed by new Gulf friendships after the Gaza war, is scouting for ports and pipelines.

Absent a credible regional order, the Horn risks becoming a chessboard on which others play out distant rivalries.

Regional and multilateral institutions meant to calm storms have wilted. The Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), the African Union (AU), and even the United Nations (UN) look marginalised after years of paralysis. Promises of inclusive governance ring hollow.

In Somalia and Sudan, violent conflicts mutated into business models. Armed groups, bloated on war economies and foreign stipends, treat civilians, bridges and grain stores as fair game. Disinformation and ethnic incitement on social media splinter communities into rival militias.

The bill for violence is ruinous. Ethiopia’s recent northern civil war killed hundreds of thousands, uprooted millions, and left reconstruction costs of roughly 20 billion dollars. Annual port charges, by contrast, look like small change. A hard-headed ledger favours negotiation over gunfires.

A sensible strategy would start by muting the word bombast. Any hint of forced acquisition of another country’s territory merely stiffens opposition. If outsiders are indeed fanning the flames, their role is best examined in neutral forums such as IGAD or the AU, which at least lend legitimacy.

The purpose should not be to crush Ethiopia’s ambitions or belittle Eritrea’s fears. It is to move the quarrel into orderly legal channels. International law already guarantees Ethiopia transit without imperilling Eritrean sovereignty. Bilateral talks could forge a package of secure corridors, joint logistics parks, and perhaps an Ethiopian stake in a port, all without redrawing a single border.

Regional leaders could appoint an independent task force to map conflict drivers, draft rules for external involvement, and review the operations of IGAD and the AU. A collective security pact, anchored in non-aggression and joint patrols, could prevent proxy wars.

A co-operative deal would unlock investment, expand regional trade, and, more importantly, could allow governments to shift scarce funds from artillery to schools, clinics, rural roads, and the irrigation pumps that farmers sorely need. The international community should reward such co-operation and penalise militarisation.

Officials forecast that Ethiopia’s economic output, inching to 200 billion dollars by the end of the current decade, brandished as proof that the dependence on Djibouti is unsustainable. The arithmetic could be seductive, yet it masks the hollowed factories, scorched farms, and uprooted families left by the recent civil war and the ongoing violence.

Time is short. Each week, fresh affronts cross the frontier. Every word strike makes compromise harder. Geography could be a constraint; it should not be viewed as a destiny. It may be fixed, but politics is elastic. With measured words, legal instruments, and a dash of imagination, the Horn of Africa can loosen its chains without spilling more blood.

PUBLISHED ON

Jun 14,2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1311]

My Opinion | 133429 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 129943 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 127749 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 125303 Views | Aug 07,2021

Aug 9 , 2025

In the 14th Century, the Egyptian scholar Ibn Khaldun drew a neat curve in the sand....

Aug 2 , 2025

At daybreak on Thursday last week, July 31, 2025, hundreds of thousands of Ethiop...

Jul 26 , 2025

Teaching hospitals everywhere juggle three jobs at once: teaching, curing, and discov...

Jul 19 , 2025

Parliament is no stranger to frantic bursts of productivity. Even so, the vote last w...