Nov 23 , 2024. By Yemanebrhan Kiros ( Yemanebrhan Kiros (yomemech@gmail.com), manager at Yomener Energy Auditing & Engineering Plc. )

Contractors can potentially be competitive players on the African continent and beyond. Achieving this will require introspection, strategic planning, and a willingness to invest in human and material resources. By encouraging a culture of excellence, accountability, and continuous improvement, the construction sector can transform from a symbol of unrealised potential into a pillar of sustainable growth, argues Yemanebrhan Kiros (yomenerenergyaudit@gmail.com), manager at Yomener Energy Auditing & Engineering Plc.

The construction sector has been booming for nearly two decades, with new housing developments, commercial buildings, hospitals, university facilities, and airport terminals transforming the skylines. The surge has immensely bolstered the GDP, contributing from 4.5pc in 2012 to 10pc a decade later, averaging 7.39pc. It also spurred the growth of specialised subcontractors in fields from electromechanical systems and electrical installations to data security, fire suppression, and fire alarms.

Yet beneath this veneer of progress lies a troubling reality. Many of these subcontractors struggle to sustain their businesses beyond a decade, and the quality of their work often falls short, leaving expensive installations nonfunctional shortly after completion.

Despite substantial investments, often amounting to billions of Birr, in modern installations for public projects like hospitals and universities, many systems fail to function effectively post-inauguration. Advanced systems such as forced ventilation, air conditioning, firefighting equipment, and specialised air conditioning for operating theatres are installed but remain underutilised or completely dormant. The disconnect between investment and utility should raise concerns about the stewardship of taxpayer money and the country's scarce foreign currency reserves, often used to import these sophisticated systems.

The responsibility for these failures does not rest solely on the subcontractors. Governmental and private organisations are often unprepared to operate, maintain, and preserve these complex systems. Technical teams on the client side may not fully understand how the installations are supposed to function or their intended purposes. As a result, the concepts behind these substantial investments linger only on paper, failing to translate into tangible benefits for building occupants.

Challenges permeate every stage of construction, from design to testing, commissioning, and handover. A pervasive lack of robust standards and guidelines exacerbates these issues. There are also no stringent building codes that enforce quality workmanship, safety protocols, and long-term serviceability of installations. The regulatory gap allows subpar work to go unchecked, undermining the industry's overall integrity.

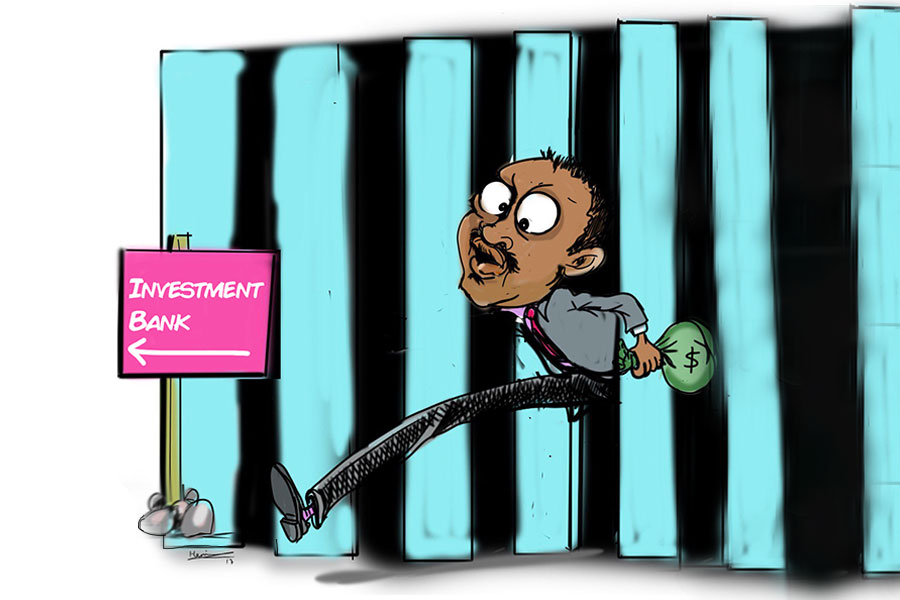

Corruption and poor project administration further erode confidence in subcontracted work. Financial mismanagement is rampant among contractors. Owners and shareholders often indulge in extravagant spending on personal luxuries rather than reinvesting in their companies. The neglect manifests in inadequate staff training, insufficient construction equipment and tools, low salaries, and a lack of worker motivation. Such practices contribute to early business failures and a cycle of companies entering and exiting the market, causing valuable experience and expertise to be lost.

Frequent changes in tax laws and regulations pose additional limitations. Many contractors lack the knowledge to overcome these shifts, leading to compliance issues and financial penalties that can cripple their operations. The instability discourages investment in capacity building, as companies prioritise short-term survival over long-term growth.

The way contracts are awarded also impedes industry advancement. Firms often secure projects based on personal connections rather than merit, diminishing incentives to improve quality or invest in skill development. The network-driven system stifles competition and perpetuates mediocrity, as companies rely on who they know rather than what they can do.

Despite these systemic issues, a few companies have managed to break the norm. Illustrious for their quality work, some have even secured contracts abroad, leveraging their domestic experience to achieve international success. These outliers demonstrated that Ethiopian contractors can compete on a larger stage with the right approach. Given the volume of projects and investment size within the country, more firms should have been able to join this success wagon, foretelling untapped potential within the sector.

However, relying solely on subcontracting is not a sustainable strategy. Frustrated by the performance of their subcontractors and motivated by financial interests, some of the major contractors are establishing their own divisions to handle specialised work. While this might seem like a solution, it risks creating additional problems. Specialised tasks require dedicated management and expertise, and spreading resources too thin could compromise quality further. The approach could stifle the development of specialised subcontractors, limiting opportunities for young engineers to hone their skills and contribute meaningfully to the industry.

Young professionals have entered the industry with enthusiasm and innovative ideas, contributing to job creation and reducing unemployment rates. Their entrepreneurial spirit is commendable, reflecting a can-do attitude that should bode well for the sector's future. However, a lack of long-term vision prevents them from expanding their services and product offerings. The short-sightedness is a constraining factor in their inability to grow commensurately with their investments and time in the market.

Education systems may also bear some responsibility for the industry's shortcomings. A possible overemphasis on immediate success without adequate preparation leaves professionals ill-equipped to handle complex projects. Insufficient training in financial management contributes to the prevalent mismanagement seen across companies.

Nonetheless, the recent policy shift allowing foreign workers into the country introduces another layer of competition. Foreign firms could easily overtake local subcontractors, particularly if the latter do not address their performance issues. The potential displacement should inform policymakers of the urgency for Ethiopian subcontractors to enhance their technical and financial management capabilities.

One viable path forward is the establishment of third-party verifiers to assess the quality, reliability, and performance of specialised work. Such entities could help bridge the knowledge gap and compensate for clients' and consultants' limited capacity. Encouraging this practice would require substantial investment in testing equipment and technical expertise but could considerably elevate industry standards. Currently, the industry lacks this crucial layer of oversight in the construction sector.

Professional associations, government bodies, and educational institutions should collaborate to address these systemic issues. Implementing stringent building codes and standards can enforce quality and safety. Encouraging merit-based competition for contracts can incentivise companies to invest in capacity building. Financial education and support can help firms deal with regulatory complexities and manage resources effectively.

PUBLISHED ON

Nov 23,2024 [ VOL

25 , NO

1282]

Photo Gallery | 147687 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 137783 Views | Apr 26,2019

My Opinion | 134427 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 130991 Views | Aug 21,2021

Aug 30 , 2025

For Germans, Otto von Bismarck is first remembered as the architect of a unified nati...

Aug 23 , 2025

Banks have a new obsession. After decades chasing deposits and, more recently, digita...

Aug 16 , 2025

A decade ago, a case in the United States (US) jolted Wall Street. An ambulance opera...

Aug 9 , 2025

In the 14th Century, the Egyptian scholar Ibn Khaldun drew a neat curve in the sand....