My Opinion | 133416 Views | Aug 14,2021

Jun 15 , 2025. By BEZAWIT HULUAGER ( FORTUNE STAFF WRITER )

Unilever, the British-Dutch multinational, has become the first foreign company licensed to import finished goods directly into the country, following revisions to investment policies. Vaseline petroleum jelly and lotions, sourced from Unilever’s factories overseas, will soon arrive in the local market, marking a shift from the previous practice of importing goods only through third-party distributors.

The General Manager of Unilever Ethiopia, Nesibu Temesgen, confirmed that his company actively lobbied for the policy changes now allowing foreign firms to import and sell finished goods directly. Unilever Ethiopia distributes its products through 53 major distributors serving around 100,000 retail shops. With the introduction of this new directive by the Ethiopian Investment Commission, the company will also expand its sales through wholesale.

Deputy Commissioner Dagato Kumbe disclosed the government’s intention behind the policy shift.

“We believe the new directive will promote investment in the country,” he told Fortune.

According to Dagato, around 100 investors have already received licenses for import, export, wholesale, and retail activities since the directive was adopted.

Unilever's imports will initially serve as a market test. Over the next three years, the company plans to study product scalability, consumer attitudes, and market acceptance. The research will inform decisions about potential domestic manufacturing. Nesibu stated that a product should generate at least 10 million euros in annual revenue to be considered for local production. Unilever has made its intent to steer clear of retail operations, preferring to focus on brand development and training local workers.

“Our partners have to benefit from the retail value chain,” Nesibu told Fortune.

An official from the Investment Commission, speaking anonymously, admitted that the previous directive had been overly restrictive, discouraging many potential investors. He insisted that a regulatory easing was necessary to attract foreign investment. Drawing parallels to Ethiopia’s experience with industrial parks, initially launched in 2008 but formally regulated two years later, the official argued that easing rules would similarly encourage investment in trade sectors.

The 2024 law, though more open than earlier versions, had still proved restrictive. Foreign investors previously faced stringent requirements. Exporters of raw coffee, for instance, were required to demonstrate at least 10 million dollars in annual procurement over the past three years and a commitment to export similar amounts in their permit year. Comparable restrictions applied to other products such as oilseeds, khat, pulses, and hides. Livestock exports had been an exception, allowing new entrants without prior procurement records if they provided detailed market analysis and purchase orders.

Further barriers existed for import and retail trade permits. Importers had to be manufacturers themselves or agents of manufacturers, or existing Ethiopian manufacturers exporting over 50pc of their output. Alternatively, they had to commit to importing at least 10 million dollars worth of goods annually. Retail investors were required to establish infrastructure, such as supermarkets or hypermarkets, with a substantial minimum floor area.

Under the new law, these barriers have largely disappeared. Foreign investors may now freely export previously restricted commodities like coffee, oilseeds, khat, pulses, hides and skins, forest products, and livestock, provided they submit due diligence reports affirming their financial integrity and absence of illicit connections. They can also participate in import trade (excluding fertiliser and petroleum) and wholesale markets previously reserved exclusively for domestic businesses.

Retail trade has also been opened to foreign investors, although specific financial conditions still apply. Foreign retail businesses should possess a minimum paid-up capital of 2.5 million dollars in cash and assets, validated by a professional valuation. On a case-by-case basis, the Commission may approve reputable single-brand retailers with less capital.

"We’re also the first foreign company to secure a license to export coffee from Ethiopia,” Nesibu revealed.

Unilever established its local presence as a manufacturer in 2014, producing 32 items, including well-known brands such as Lifebuoy, Omo, Knorr, Sunlight, and Signal, at its plant in the Eastern Industrial Zone near Modjo. The company employs around 7,000 people, and pays over two billion Birr annually in taxes.

Nesibu, appointed last April as the first Ethiopian CEO, aspires to triple Unilever’s annual sales in Ethiopia to 200 million euros within five years. His appointment follows a recent trend among multinational companies, including Coca-Cola Beverages Africa and Pepsi International, to appoint local leaders to spearhead growth.

Despite these bold objectives, product innovation has encountered obstacles. Unilever had set a target to generate 20pc to 30pc of its revenue from innovative products. However, two recent product introductions, Knorr Shiro and Sunlight Bar Soap, failed during local market testing. Sunlight bar soap was discontinued two months ago. According to Nesibu, the market had easy access to homemade bar soaps, and consumers primarily associated Sunlight’s brand with clothing and skincare rather than sanitation.

Knorr Shiro, a traditional dish repackaged for export, also faced challenges. Nesibu believes that because shiro is traditionally homemade, converting it into a branded product proved unprofitable. Export efforts faced further complications.

Tewodros Y. Bishaw, founder of TYB LLC, recounted receiving six tonnes of Knorr Shiro by air to the US, arranged through Unilever’s discounted pricing. However, the shipment was damaged at customs and had a shelf life of less than a year, which is inadequate for proper market distribution. The product expired before it could reach consumers effectively, forcing TYB LLC to recall stock across various US states.

Tewodros has since sought compensation for damages, logistical issues, and disposal costs. Unilever acknowledged errors and promised compensation. Nonetheless, Nesibu maintained that Unilever’s liability was limited. According to him, the shipment was initially intended for local markets and was indirectly sold to TYB LLC. Unilever agreed to refund only the initial purchase cost of approximately 3.5 million Br.

"We agreed out of goodwill, not out of responsibility," Nesibu said.

Not everyone views these new developments positively.

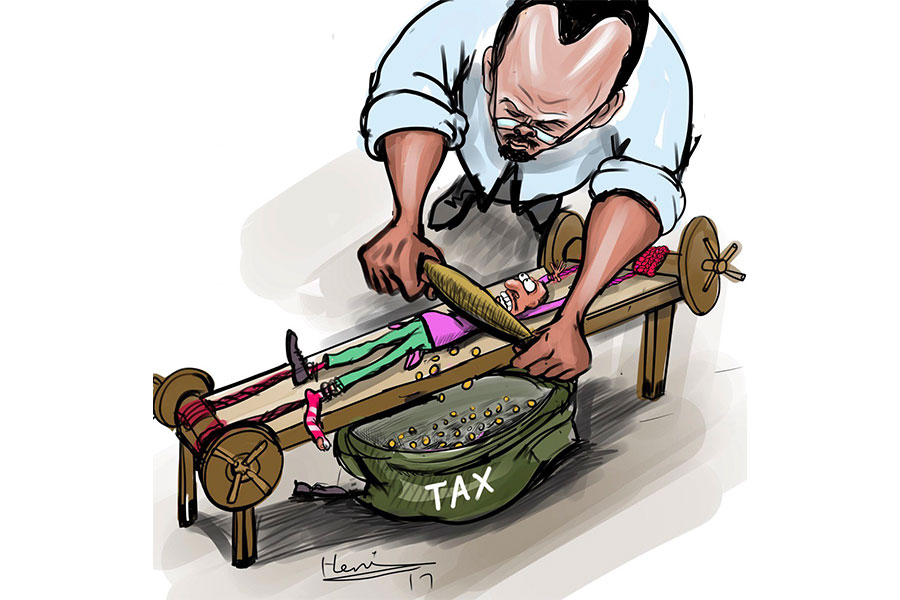

Dawit Kejela, a tax consultant with 10 years' experience at Ethiopia’s Ministry of Revenue, voiced concerns. He warned that the directive could threaten local businesses, particularly importers and retailers, allowing large multinational corporations to dominate the market, which could potentially lead to capital flight and weaken domestic production.

“Local businesses could be left struggling without adequate support or training,” Dawit warned.

He argued that the minimum investment threshold would primarily attract large foreign entities, effectively sidelining smaller local competitors. Dawit recommended implementing safeguards, such as a transfer pricing tax, to ensure the government captures a fair share of the profits of foreign companies. He argued that direct exports by foreign firms should be restricted, mandating value addition within Ethiopia to support local manufacturing.

"Without safeguards, the country risks becoming a dumping ground for foreign companies," Dawit said.

PUBLISHED ON

Jun 15,2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1312]

My Opinion | 133416 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 129931 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 127736 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 125288 Views | Aug 07,2021

Aug 9 , 2025

In the 14th Century, the Egyptian scholar Ibn Khaldun drew a neat curve in the sand....

Aug 2 , 2025

At daybreak on Thursday last week, July 31, 2025, hundreds of thousands of Ethiop...

Jul 26 , 2025

Teaching hospitals everywhere juggle three jobs at once: teaching, curing, and discov...

Jul 19 , 2025

Parliament is no stranger to frantic bursts of productivity. Even so, the vote last w...