My Opinion | 129754 Views | Aug 14,2021

May 24 , 2025.

First came the trickle, then the torrent. On a humid night in late March, a low-lying neighbourhood on Addis Abeba’s southeastern fringe watched its usually placid stream surge over the banks, punch through masonry walls and fill every room in sight. Textbooks dissolved, family photographs warped, and a day labourer who had spent years building his house found himself sleeping on a relative’s floor, waiting for the next storm. Residents insist the heavens are only half to blame. For months, they had watched lorry-loads of soil and cement waste slide off construction sites upstream, while factories let oily effluent creep downstream after dusk. When the rain arrived, the clogged channel could not cope. City officials, who count about 400 people at risk in this pocket alone, accept that drainage is blocked and defences are absent. Their solution is to move families elsewhere, a prospect as grim as the floods themselves.

The capital’s vulnerability is carved into its geography. Three rivers — Bantyeketu, Kebena and the larger Akaki — thread a basin hemmed by hills, their tributaries draining everything from forested slopes to corrugated-iron roofs. Yet, those waters double as rubbish tips and industrial outlets. Stretches of the Akaki are now deemed “dead”, while its smaller branch is an open sewer. A United Nations-backed rescue plan is on the drawing board, but for now, the city irrigates vegetables with polluted water and hopes groundwater will not be tainted in turn. Concrete, not rainfall, is the real accelerant. Nearly a 10th of new buildings over the past decade have risen inside what hydrologists describe as the 100-year floodplain, and four-fifths of residents live in informal settlements where drains are scant and insurance is mythical. When prolonged drought bakes the soil, a condition scientists say will be 53pc more common by mid-century, downpours simply bounce off the hardened surface. In March 2023, a single cloudburst tore a riverside house from its foundations, drowning a mother and her children before neighbours could reach them.

The engineering meant to spare the city is scarcely fit for purpose. Many canals were dug for a five-year storm; manholes are identical in size and spaced too far apart. Officials boast of clearing 400Km of drains in nine months, however, uncovered manholes invite fresh rubbish; more than 15,000 people remain in zones officially classed as high-risk. Parliament has tightened penalties for dumping waste into rivers, but enforcement is weak and overlapping bureaucracies guarantee delays. Climate projections offer little comfort. Daily temperature peaks are expected to climb by 1.7°C by the 2040s, allowing hotter air to store, and then unleash, greater volumes of water. According to the city administration's count, the city’s population is nearly five million. It is projected to almost double within a decade, erasing more green spaces that might have soaked up the runoff. Unless drainage is upgraded and construction in floodplains curbed, Addis Abeba’s rainy-season anxiety seems destined to harden into a permanent state of siege.

PUBLISHED ON

May 24,2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1308]

My Opinion | 129754 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 126064 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 124073 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 121865 Views | Aug 07,2021

May 24 , 2025

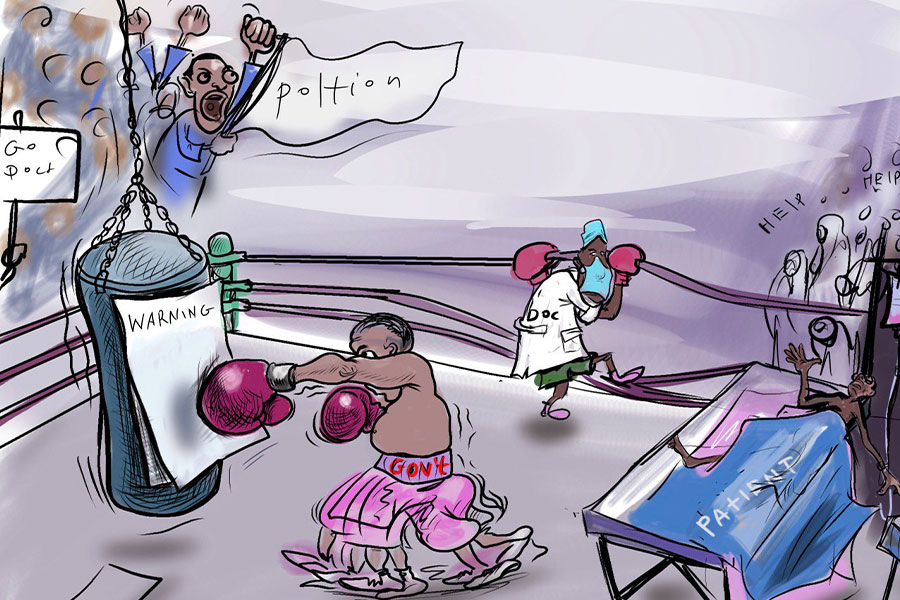

Public hospitals have fallen eerily quiet lately. Corridors once crowded with patient...

May 17 , 2025

Ethiopia pours more than three billion Birr a year into academic research, yet too mu...

May 10 , 2025

Federal legislators recently summoned Shiferaw Teklemariam (PhD), head of the Disaste...

May 3 , 2025

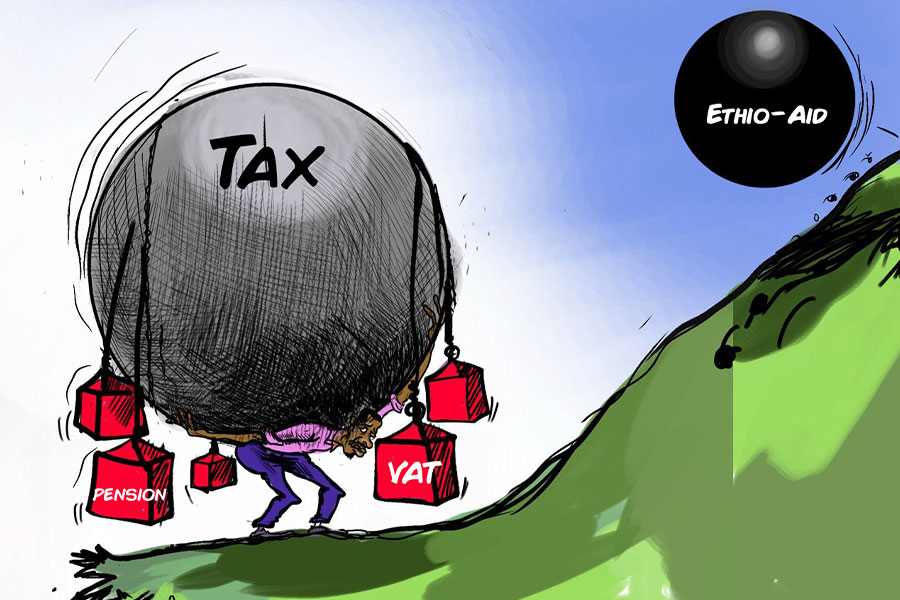

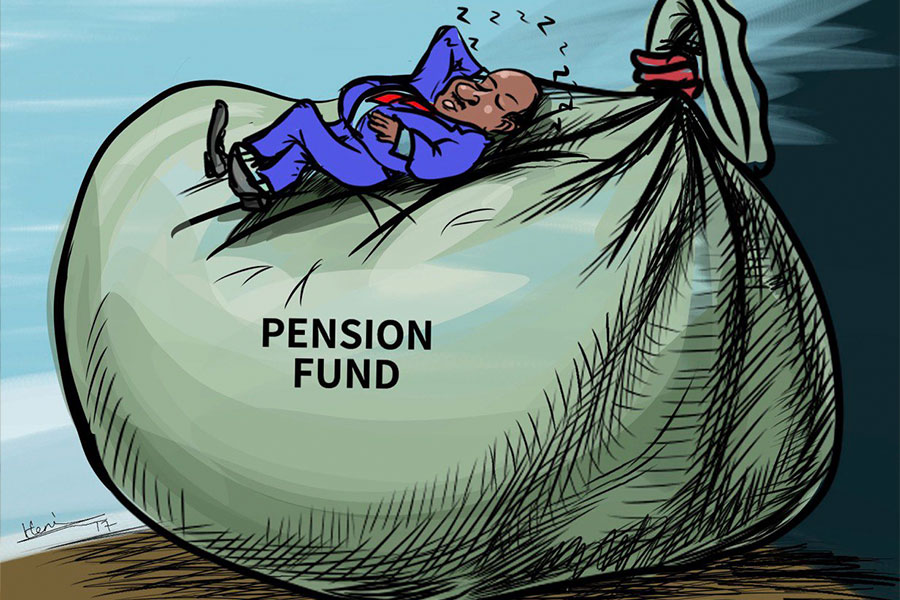

Pensioners have learned, rather painfully, the gulf between a figure on a passbook an...