Commentaries | Jul 13,2019

Feb 27 , 2021

By Fisseha Adugna

Despite credible reports that Sudan went deep into territories under Ethiopian administration, the latter's government has exercised maximum restraint and called for a dialogue to solve pending boundary issues. If this is not the case, the region can easily go back to the old era of a destructive policy of mutual destabilisation, writes Fisseha Adugna, former Ethiopian ambassador to the United Kingdom and former member of the Joint Ethiopia/Sudan Boundary Commission from 2001 to 2006. The views expressed in the article are those of the writer and do not represent those of the Ethiopian government.

On November 6, 2020, the Sudanese military carried out unprovoked aggression against Ethiopia. Since then the Sudanese military campaign has continued and now they have occupied, by force, territories previously under Ethiopian administration. Despite Ethiopia’s repeated calls for peaceful settlement of the boundary disputes, Sudanese military leaders have intensified their military and propaganda campaigns against Ethiopia. Such unprovoked and irresponsible military adventure has posed grave consequences for the bilateral relations of the two countries and for peace and security in the region.

If the Sudanese government continues in this course of action, the situation can easily spin out of hand and lead to a dangerous armed conflict between the two nations. As a consequence of unexpected attacks by the Sudanese army, Ethiopian citizens reportedly lost their lives, many farmers were displaced, their farms and properties were destroyed or looted, and their livelihood is hanging in the balance.

Following this attack, Sudanese military leader Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan (Lt. Gen.) has given somewhat conflicting accounts about his action. First, his government denied that his forces ever crossed the international boundary.

“The Sudanese army had been redeployed along the Sudanese side in the border with Ethiopia,” Sudanese Foreign Ministry Spokesman Mansour Boulad said.

Later on, the General justified his action, which he said was to “re-take the land that was taken away by Ethiopia 25 years ago.” In a rather bizarre explanation, he even said that “his actions were in response to Ethiopia’s request to close the borders.” Sudanese press widely reported that the Sudanese army bragged that Sudan had re-occupied 80pc of its land that was seized by Ethiopia.

Despite credible reports that Sudan went deep into territories under Ethiopian administration — as deep as 50Km in some accounts — the Ethiopian government has exercised maximum restraint and “demanded the withdrawal of Sudanese forces from Ethiopian territories” and called for a dialogue to solve pending boundary issues that existed for a long time. Sudanese authorities are yet to respond positively.

In the meantime, concerned neutral parties including the African Union (AU), the Republic of South Sudan and Turkey showed their interest to mediate between Ethiopia and Sudan. If this materialises, it will be a positive development and consistent with Ethiopia’s policy of peaceful settlement of border disputes between two countries.

But how did these two neighbourly countries get to this point?

It starts with two treaties signed between Ethiopia and the United Kingdom (Sudan’s former colonial power) in 1902 and in 1907 that delimited the boundary between the two countries. The treaties required the formation of a joint bilateral commission to demarcate the boundary on the ground.

However, the boundary demarcation was carried out unilaterally in 1903 and 1909 by Charles Gwynn (Maj.), later knighted, representing the British Government. Ethiopia objected to Gwynn’s unilateral demarcation, as it was not consistent with the treaty’s requirement of setting up a joint boundary commission to demarcate the boundary.

The Major indicated that he had authorisation from Emperor Menelik II without producing any evidence. The British and later on the successive Sudanese governments had argued in the same line, but they also failed to produce any evidence. That was where the controversy began, a century ago, not over the past 25 years as Sudanese authorities indicate.

The outcome of the unilateral demarcation of the boundary was a history of friction and tension throughout the colonial period. Neither have matters improved much after Sudan attained independence in 1956.

Fast forward to July 18, 1972, Ethiopia and Sudan signed the Exchange of Notes of 1972 that stated basic acceptance of the boundary line as initially demarcated in the 1900s with the necessary rectifications and adjustments along the common boundary. Article III of the agreement set guidance on how both parties should handle the disputed territories stretching from Mount Dagleish (near Dinder River) northward to the Setit River, which is the tri-junction point of Sudan, Ethiopia and Eritrea.

The agreement demanded, first and foremost, the identification of all de facto holdings of territories and the limits of settlement and cultivation in the disputed areas. Once these were identified, the Agreement specified that both parties should find an amicable solution to re-demarcate the boundary. The agreement emphasised strongly that the status quo must be maintained until a mutually acceptable agreement is reached to address the problem.

“The status quo shall be respected until final disposition of the case by agreement between the two governments,” Article III stipulated. “The governments of Sudan and Ethiopia shall study the problem resulting from settlements and cultivation by nationals of either nation in the territory of the other with a view to finding an amicable solution.”

Following the signing of the agreement, both countries established joint boundary commissions in order to implement the decisions agreed to in the Exchange of Notes. In the course of long boundary negotiations since 1972, one would wish that both countries achieved better progress. But we know that such progress was slowed down partly by domestic political and security problems, which frequently took place in both countries and were partly due to the intransigence and inflexibility by Sudanese negotiators to find an amicable solution.

Despite the lack of the desired progress at boundary re-demarcation, however, both countries have worked together for decades, which assured relative peace and stability at the boundary areas. They even carried out successful joint cross-boundary projects aimed at promoting mutual interest, which has become a symbol of good neighbourly relations for many African countries.

In 2002, Ethiopia and Sudan showed genuine interest in resolving all pending issues at the contested areas and set up the Ethiopia/Sudan Joint Special Committee to find a lasting solution to the problem in the disputed areas. Under the Committee, the Ethiopia/Sudan Joint Select Working Group composed of known experts from both countries with a mandate to conduct field studies in the disputed areas was established.

After a detailed and extensive field study, the group jointly identified de facto holdings and issued its joint report. This was an important milestone in the negotiations between the two countries, because for the first time the existing de facto holdings of Ethiopia and Sudan that are consistent with the 1972 Exchange of Notes were jointly identified. The remaining work was to find an amicable solution and go ahead in re-demarcating the common boundary.

In 2019, the Omar Al-Bashir regime was toppled, and the current government came to power in Khartoum. It was Ethiopia’s expectation that the Joint Special Committee would be allowed to finalise its mission, which is to identify amicable solutions to the problem. However, the Sudanese military, on the contrary, made a unilateral decision to settle the dispute by force in the contested areas (at a place they called Al Fashaga) taking advantage of Ethiopia’s domestic situation. This Sudanese action is a serious setback to time tested good neighbourly relations between the two countries. More importantly, it is a clear violation of a key article of the 1972 Exchange of Notes where both parties agreed to maintain the status quo until the final disposition of the case by agreement between the two governments.

It is also a violation of the joint agreement that identified the de facto holdings of territories in the disputed areas. The Sudanese officials should know that there was no amicable solution accepted by both parties — which makes their military action illegal and belligerent.

In the last few years, Ethiopia and Sudan have begun their own political transitions led by new generations in their respective countries. Accordingly, both leaderships showed their willingness to help each other fulfill the democratic aspirations of their peoples. They also renewed their commitment to pursue diplomatic and peaceful means to address boundary issues.

To that effect, high-level visits took place involving Sudanese Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok, Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan and Vice-president of the Sovereign Council Mohamed Hamdan "Hemeti" Dagolo.

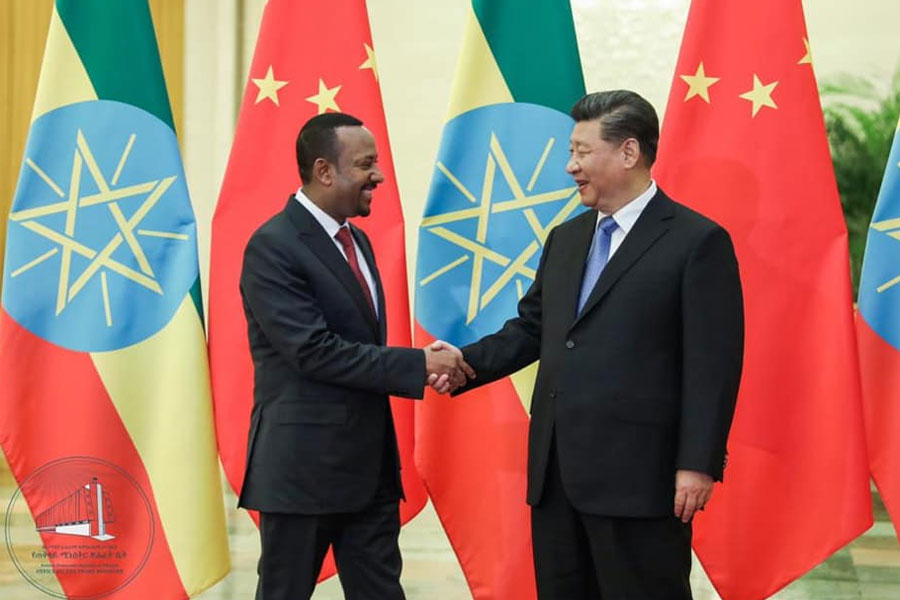

Ethiopian officials also made frequent visits to Khartoum. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) helped the Sudanese parties to establish a transitional arrangement between the civilians and military representatives. He attended the signing ceremony in Khartoum that created the transitional government in Sudan. Furthermore, Ethiopia has also participated in the peacekeeping efforts in Darfur and Abyei. When territorial disputes erupted between Sudan and the new state of South Sudan, Ethiopia mediated between the parties and helped avoid major military clashes between them.

Recently, Ethiopian Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Demeke Mekonnen travelled to Khartoum to avert military confrontation and tried to persuade Sudan to pursue diplomatic channels to resolve the current crisis.

Despite all these positive developments between the two countries, Sudan chose to occupy territories it captured by force when Ethiopia moved its Defence Forces from the border area to reinforce its law enforcement operations in Tigray Regional State.

For Ethiopians, the unexpected attack by the Sudanese military remains perplexing. Many believe that the Sudanese are their brothers and sisters. The peoples of the two countries have lived side-by-side for millennia and drink from the same river, the mighty Blue Nile. They both have a history that goes back to antiquity. They share many heritages together including people, religion, languages, culture and destiny. They even share a name with a similar meaning. Ethiopia means the country of black face in Greek and "bilad al-Sudan" means the land of black people in Arabic.

Both countries have gone through ups and downs in their modern history. They both were exposed to long devastating civil wars — after which the new nations of Eritrea and South Sudan were born. During those tough times, the peoples of both countries gave each other helping hands and welcomed those who sought refuge in each other’s country. Such solidarity between the people remained unbroken even when government-to-government relations were at their low points in history.

What went wrong suddenly?

It seems that recent Sudanese actions are influenced by two factors, internal and external. On the domestic front, the Sudanese domestic situation is increasingly deteriorating. The coalition between the military and civilian authorities is heading toward a stalemate and threatens the fragile political transition in Sudan. The military led by General Burhan and his powerful Deputy, General Hamdan Dagalo, are trying to bring the situation under control by undermining the civilian Prime Minister, Abdalla Hamdok.

Making matters worse, following the recent withdrawal of the UN and African Union Peacekeeping Forces at the beginning of the year, ethnic clashes involving armed militias have begun in Darfur, with thousands losing their lives, tens of thousands displaced, and many fleeing to neighbouring countries.

Domestic discontent, pushed further by a rising cost of living, that led to civil unrest and mass demonstrations in many parts of the country has been followed by state of emergency declarations in many parts of the country.

It is under such circumstances that Sudan accused Ethiopia for taking away territory “25 years ago” and waged a military campaign to retake it. Many observers believe that this is a deflection tactic by the military in Sudan hoping to “manage” domestic tensions.

On the foreign relations front, recent developments in the region have put Sudan in the spotlight. The construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) and the politics surrounding it have attracted international attention to the Ethio-Sudan boundary. The Dam is only about 20Km from the Sudanese border.

It was also international news when two years ago Omar Al-Bashir’s government was toppled and replaced by a transitional government that promised democracy in Sudan. The country’s subsequent removal from the US terrorist list has brought Sudan back to the fold of the international community. Following these developments, competing foreign powers have established their presence in Khartoum. Regional analysts are even pondering that Sudan has become a convenient ground for regional geopolitical intrigues.

Sudan’s vulnerability to foreign powers is not new, but recently it is getting worse. Egypt has taken the biggest lead. After its absence for nearly 30 years during the time of Omar Al-Bashir, it is now returning back to Khartoum. Egypt’s main preoccupation is to bring Sudan on its side in its disputes with Ethiopia over the GERD.

As a result, Sudan’s inconsistent pronouncements on the GERD have become confusing. Many Sudanese officials have asserted that the GERD has many benefits to their country. For this position, they were even denounced by Egypt and the Arab League. Sudan also entertained bitter complaints against Egypt for occupying Sudanese territory at Halaib Triangle, located at their common border on the northeast African coast of the Red Sea.

Why there is a sudden change of heart now, no one knows for sure. But it is evident that Sudanese military leaders chose to compromise their county’s long-term national interest in exchange for a short political advantage ostensibly over Ethiopia. It is comical that Egypt issued a press statement warning Ethiopia not to respond against Sudan's invasion. Sudan and Egypt also conducted a joint military exercise a few weeks ago — a message clearly meant for Ethiopia. Despite Sudan’s pretenses to look the other way, Egypt’s long historical ambition of domination and stewardship over Sudan has never gone away.

There are also other foreign powers that have established their presence in Khartoum and work to influence Sudan’s behaviour. Saudis and Gulf Arab states, as well as the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation and the Arab League, have their presence in Khartoum. Following Sudan’s removal from the US terrorist list, the United States, the United Kingdom and the European Union have strengthened their presence in Sudan. Recently, Israel has established diplomatic relations with Sudan and opened its embassy in Khartoum.

The geopolitical implication of such a growing foreign presence next door to Ethiopia and the region should be carefully watched. It could very well be that Egypt and its allies in the Arab world, in close consultation with some powerful military brass within the Sudanese defense forces, might have encouraged the Sudanese government to claim territories at a time when Ethiopia is preoccupied with its domestic issues.

This development is unfortunate. While the rapprochement between Sudan and Egypt is the policy choice of the two countries, it will be regrettable if the Sudanese military leaders are used to advance Egypt’s ambition over Ethiopia.

Sudan’s unexpected invasion of Ethiopia and its refusal to withdraw from the territory it occupied by force is a clear violation of the agreements reached between the two countries. It is also a breach of trust between the two countries. Needless to say, November 6, 2020, will go down in the history of Ethio-Sudanese bilateral relations as a day of betrayal by Sudanese military leaders against their neighbour Ethiopia.

It is the hope of many in Ethiopia that Sudan will be an agent of peace and stability in the region. If that is not the case, our region can easily go back to the old era of a destructive policy of mutual destabilisation. We all know that we cannot demarcate our common boundary by military means. We also know very well that violence cannot assure good neighbourly relations.

Dialogue is the only viable option. Based on mutual understanding, flexibility and give and take, it will assure a win-win outcome for all. The people of Ethiopia and Sudan deserve better — they deserve peace, stability and economic cooperation. Ethiopia and Sudan should join hands to fight their common enemy — poverty.

PUBLISHED ON

Feb 27,2021 [ VOL

21 , NO

1087]

Commentaries | Jul 13,2019

Addis Fortune | Nov 09,2019

Agenda | Apr 06,2019

Radar | Dec 19,2020

Radar | Mar 20,2021

Commentaries | Feb 12,2022

Fortune News | Apr 12,2020

Radar | Oct 16,2021

Fortune News | Sep 01,2024

Fortune News | Apr 26,2019

My Opinion | 131819 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 128203 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 126147 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123767 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 5 , 2025

Six years ago, Ethiopia was the darling of international liberal commentators. A year...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jun 14 , 2025

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal legislature gave Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) what he wanted: a 1.9 tr...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

In a city rising skyward at breakneck speed, a reckoning has arrived. Authorities in...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A landmark directive from the Ministry of Finance signals a paradigm shift in the cou...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Awash Bank has announced plans to establish a dedicated investment banking subsidiary...