Fortune News | Oct 16,2021

Finding a job in the Ethiopian labour market had been all but a pleasant experience for Lamesgen Wubshet, a graduate of computer engineering from Meqelle University. He spent three years in search after leaving campus. He had to walk a lot, spend sleepless nights, and endure many stressful moments to find one. Frustrated, he eventually came up with the idea of capitalising on the problem facing him and countless many of his peers.

Lamesgen was perhaps one of the 19 million Ethiopians who were unemployed in January 2020, according to the Central Statistical Agency (CSA). But it takes a determined soul's relentless effort to find recent data on how many Ethiopians are without jobs. The Agency, the authoritative source for such figures, puts the rate at 18.7pc last year, showing a modest 0.4pc decline from the previous year. At 12.2pc, the number of unemployed women was double the size of men such as Lamesgen.

He eventually gave up his search for employment and instead focused his energy on creating something of his own. The computer programming knowledge he picked up during his academic years came in handy. Lamesgen developed an online job portal, GeezJobs, hoping to connect employers with those seeking work. He went to the Addis Abeba Trade & Industry Bureau, whose officials often claim it only takes less than a week to get a business license.

They told Lamesgen to get a tax identification number (TIN) from the city’s Revenues Bureau. The officials at the Bureau asked him to provide them with a rental agreement.

“What do I need an office for,” Lamesgen replied, explaining the nature of his business, which can be done basically from anywhere with a decent internet connection. "I soon realised I had no choice but to comply."

For many startups, irrespective of their line of business, fulfilling such regulatory demands has proven to be an uphill battle. Starting a new endeavour has never been easy. However, Ethiopia presents unique challenges due to lengthy procedures that new establishments have to go through, not to mention the series of other problems they face, from accessing loans to finding land or workspace.

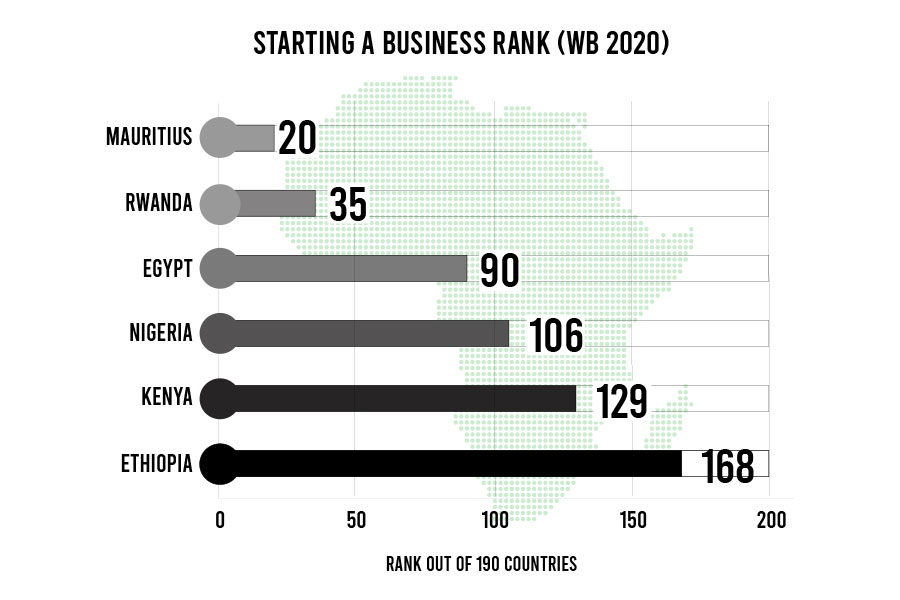

In 2020 it took an average of 32 days to complete the registration and licensing of a business in Ethiopia, which is 159 among 190 countries in the World Bank's Ease of Doing Business rankings for last year. In Rwanda, four days are all it takes to start a business, while in less than 12 days, businesses can register in Kenya, a country with a GDP comparable to that of Ethiopia, standing at 100 billion dollars.

The administration of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) has introduced a series of reforms to buck such a trend.

After taking office from his predecessor, Hailemariam Desalegn, and forming a new cabinet, the administration introduced the Ease of Doing Business Initiative. Reducing the time needed to obtain a cash register machine from seven days to three days and automating business registration and licensing were among the reforms outlined under the initiative. Different roles were assigned to 11 government institutions, among which the Ministry of Trade & Industry took charge of the first and main activity: issuing licenses.

Start-ups like Lamesgen were meant to benefit from such reforms, with the authorities planning to avail the completion of a registration process in five days. Eshete Asfaw, state minister for Trade & Industry, believes the initiative has begun to pay off as the number of licences issued since grew by half a million from the two million issued over a century.

Documents verification, a process that would take up an entire day or even longer, can now be done in hours while previous requirements for new businesses to publish names in state-owned publications has been scrapped. The time it takes to acquire a cash registration machine has been halved, Eshete claims.

This might be considered a success, but one particularly troublesome aspect of the licensing process remains a headache for business people: obtaining tax identification numbers (TIN). A business must present a TIN as part of the licensing process at the Ministry of Trade or trade bureaus under the regional states. Getting one from the Ministry of Revenues has proven to be anything but simple, as Lamesgen discovered.

His experience was not an isolated anecdotal footnote. It has been a source of much frustration for another young business aspirant.

Abigiya Kefyalew is a 26-year old tech professional who recently got started on a business of her own. She was asked to present a lease agreement as having a physical address is mandatory even for businesses that can run without an office. With a lending hand from her parents, Abigiya rented office space because this was something that she could not get around.

"I develop software and websites for different organisations," she said. "I don't actually need an office. I can work from my home or the offices of my employers."

Although this was something the administration of Prime Minister Abiy pledged to discontinue, officials never implemented it under the bureaucratic ranks. A quick visit to one of the country's busiest revenues offices tells as much.

A list of the requirements new businesses have to comply with to acquire a TIN was posted at the entrance of the branch office for the Bole District Small Business Tax Payers. Presenting valid identification and fingerprints, business people are obliged to show lease agreement – a requirement that had supposedly been removed when the initiative was kicked off three years ago. Omer Abdela, a deputy manager at the Branch Office, and his team, nonetheless, require startups to present office rental agreements or proof of ownership before issuing a TIN.

Omer says he has not received instructions from the "higher-ups at the Ministry" to go about it any other way. He, too, believes the requirement is necessary to keep track of the whereabouts of the tax registration machines handed out to businesses once they are licensed as well as the taxpayers themselves.

“The regulation states that if the business owner isn't paying the taxes, the authorities are to go to the location and serve a notice,” says Omer.

The authorities strongly believe the requirement would be made rather difficult if businesses had no registered office space. They do not see the logic of issuing a business license without knowing where it is physically located. They believe there is no way of skirting around this issue, although they conceded the process could be streamlined.

“Business addresses should be convenient for support, supervision, and inspection," said Abere Asfaw, legal director at the Ministry of Revenues. “Whatever the case may be, there should be a place where one runs the business.”

In a capital where rental fees are exorbitant, and tenants are required to deposit a minimum of six-month pay upon signing a lease agreement, aspirant business people such as Lamesgen and Abigiya find it illogical to tie up their capital. Abere says they can also use their home addresses to acquire the TIN, but that would be subject to approval following an inspection of the space.

Others have different ideas, such as requesting personal guarantors instead of office space. Samuel Girma, a business attorney, advocates this as a compromise. Lamesgen echoed this proposition that replacing the office space requirement with guarantees from kin would be sufficient to ensure compliance.

The Ministry of Trade no longer requires proof of office space to issue licenses. But, this means little as it compels businesses to present documents from other government offices which do.

“We're working on options to allow startups to get their TIN at the Ministry,” Eshete told Fortune.

Obtaining TINs are not the only issue. Lamesgen had to jump through several hoops to get his business off the ground. Given that GeezJobs is a job portal and so tied to employment, the Trade Ministry compelled him to get an accreditation from the Ministry of Labour & Social Affairs before granting him the license.

Lamesgen found out the process at the Ministry of Labour was no less difficult. He was required to present an office space of more than 100sqm and furniture and equipment to boot. The officials from the Ministry want to conduct inspections at his place of work frequently.

"There should be a way for me to check in with regulators monthly or just have them come to my residence,” argues Lamesgen.

For him, like many others of his generation, the need for office space is a nuisance. A residence would be even better as people are less likely to abandon that than an office.

“My business is online," he told Fortune. "If I'm not complying with the tax rules, it would be easy to end my business and make me accountable as they could block it from the servers."

PUBLISHED ON

Jul 03,2021 [ VOL

22 , NO

1105]

Fortune News | Oct 16,2021

Fortune News | May 01,2022

Exclusive Interviews | Dec 12,2020

Radar | Dec 26,2020

Fortune News | Jul 22,2023

My Opinion | May 21,2022

Fortune News | May 23,2021

Covid-19 | May 09,2020

Radar | Aug 14,2021

Fortune News | Jul 12,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jun 14 , 2025

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars...

Jun 7 , 2025

Few promises shine brighter in Addis Abeba than the pledge of a roof for every family...