Apr 13 , 2024.

In the hushed corridors of the legislative house on Lorenzo Te’azaz Road (Arat Kilo), a chilly reception awaited Gebremesqel Chala, the minister of Trade & Regional Integration (MoTRI). Trusted by the administration to lead crucial negotiations with the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and several other bilateral trade partners, he faced the unenviable task of delivering grim news. Export revenues had fallen short by 164 million dollars to 2.16 billion dollars in the first eight months of the fiscal year, compared to the same period last year.

The shortfall is particularly troubling for a country where foreign currency reserves barely cover a month's imports, averaging 1.5 billion dollars a month in 2023. The fuel bill, more than three billion dollars, takes the biggest share, registering a 37.6pc growth from the previous year. This expenditure consumed all the revenues generated from exports during the same year.

Undoubtedly, economic reforms are urgently needed to overhaul such a massive imbalance in external trade, causing a distorted foreign exchange regime.

The decline in exports is only a symptom of deeper structural maladies. A weak export strategy is compounded by bureaucratic inefficiencies, substandard product quality, and a supply chain compromised by insecurity from the ongoing violent confrontations. The export sector remains perilously dependent on the international coffee market, where price fluctuations directly impact national revenues. A 26pc spike in coffee prices two years ago boosted export earnings to 4.1 billion dollars. Yet a 35pc price drop erased an 11.9 million dollar gain to the 900 million dollars in earnings made the following year. Psychologists may describe such an over-reliance on coffee, comprising a quarter of the total export value, as a “maladaptive attachment,” evidencing a failure to diversify export products and to compete on quality and price on the global stage.

Major coffee buyers—Germany, Japan, Belgium, the United States, and Saudi Arabia—have halved their orders. Together, they account for more than 60pc of Ethiopia’s coffee exports. Germany cut its imports by a staggering 36,000tns last year, while Japan reduced its demand by 17,400tns, citing inflated prices, declining quality, and logistical delays as their main concerns. Such vulnerability was apparent when other traditional foreign exchange earners like khat and gold also faltered.

Khat, which had contributed 392 million dollars to export revenue two years ago, saw a 36pc decline following a surge in contraband, driven by heavy taxation and tariffs by regional authorities. In response, the Ministry doubled down its ill-advised policy. Gebremesqel centralised the regulation, requiring exporters to secure permits from the capital, a move that did little to stem the tide. Meanwhile, Kenya, a newcomer to khat export, is already threatening Ethiopia’s market share in Somalia.

The mining sector, too, is underperforming. Earnings from gold mining in regional states like Gambela, Oromia, and Benishangul Gumuz reached only half of the annual target, at about 210 million dollars. Increased contraband activities further plague the sector. The Council of Ministers is poised to approve a new export strategy, hoping to revive this crucial sector. However, the strategy may fall short without recognising that the root causes of the export woes are as much about a lack of overriding strategy as they are about the political crises that sap productivity.

Generously funded by multilaterals like the World Bank, the consulting industry may crunch all the data and create enticing PowerPoint presentations. However, there is a simple truth. Ethiopia is not producing enough to meet its basic needs, lest it realise its economic potential. Yet, this seems lost on contemporary policymakers who face the pressing need to boost productivity. Agriculture and services, which dominate the GDP, suffer from infrastructural deficiencies and low technological integration, undermining their efficiency and contribution to growth.

The agriculture sector, primarily reliant on subsistence farming, suffers from a lack of mechanisation, which keeps yields low and operations inefficient. No less, the services sector, despite its diversity, is crippled by inadequate digital infrastructure, limiting its market reach and overall performance.

Tenacious macroeconomic imbalances due to large budget deficits, high external debts, insufficient foreign direct investment (FDI), rampant inflation, and meagre export revenues mar the broader economic landscape. These are not isolated issues but interconnected, forming a web constraining economic growth and development. For instance, the heavy burden of external debt absorbs a significant portion of the federal budget for debt servicing, restricting public investment in vital sectors like agriculture and infrastructure. The lack of FDI, deterred by an ongoing armed conflict, and the low export revenues further limit the economy’s ability to integrate into the global market, thus impeding improvements in productivity.

Substantial public investment in infrastructure is essential to break out of this negative dynamic. Reliable transportation, efficient energy sources, and robust digital infrastructure can drastically transform the agricultural and service sectors by reducing costs, improving access to markets, and facilitating the adoption of modern technologies.

Technological advancements are essential. Introducing technologies like precision farming, drones, and improved irrigation systems could revolutionise productivity in agriculture. Digital platforms could expand market reach and enhance delivery for the services sector. Education and training must also be prioritised to equip the workforce with the necessary skills for these new technologies. But all these demand enormous resources at the state's disposal. If handled unwisely, such high public spending could exacerbate the budget deficit, which would displease the guys from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Policy reforms currently negotiated with the IMF could help create a more conducive environment for productivity enhancements. These reforms should simplify regulatory frameworks, strengthen property rights, and reduce trade barriers to attract more FDI, a crucial driver of technology transfer and capital investment.

However, global economic structures also play a role. International cooperation and support from development partners are vital for managing external debt and facilitating access to global markets. Yet, the ongoing conflicts in regions like Amhara and Oromia deter these partners from engaging fully. Despite these daunting challenges, the highly anticipated IMF credit facility, while helpful, should not be viewed as a panacea but rather as part of a broader strategy to stabilise the economy and stimulate a shift.

Policymakers must undertake comprehensive and coordinated efforts to address the cycle of low productivity and economic stagnation, filled by political polarisation that should be settled through negotiations. Having a political force in charge of the state with a popular mandate perceived with legitimacy to rule can help enhance supply chain management for key commodities, create better export incentives, and improve agricultural produce in quality and volume. Beyond the over-reliance on commodities like coffee, a more diversified export strategy could provide the positive dynamic for stability and growth.

Only through comprehensive and concerted efforts will they break the cycle of low productivity and economic stagnation, setting the stage for a future of sustainable development and improved living standards for citizens. Be wary; the clock is ticking.

PUBLISHED ON

Apr 13,2024 [ VOL

25 , NO

1250]

View From Arada | Feb 25,2023

Fortune News | Sep 08,2024

Money Market Watch | Apr 13,2025

Verbatim | Sep 17,2022

Radar | May 27,2023

Radar | Apr 19,2025

Commentaries | Oct 28,2023

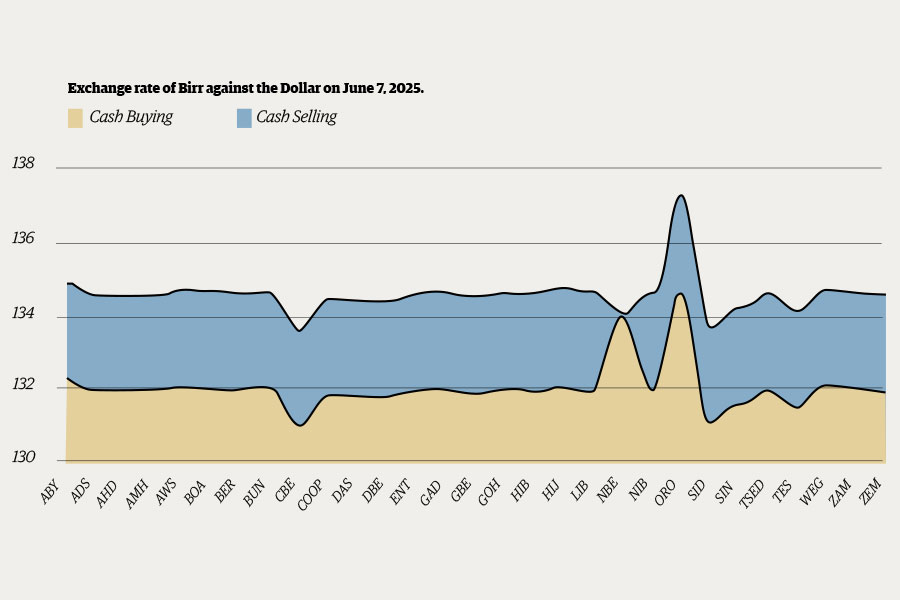

Money Market Watch | Jun 08,2025

Commentaries | Feb 13,2021

Photo Gallery | 178396 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 168596 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 159392 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 137072 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 25 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

Officials of the Addis Abeba's Education Bureau have embarked on an ambitious experim...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The federal government is making a landmark shift in its investment incentive regime...

Oct 29 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) is preparing to issue a directive that will funda...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A community of booksellers shadowing the Ethiopian National Theatre has been jolted b...