View From Arada | Apr 17,2021

Oct 26 , 2024.

When flames devoured parts of Mercato, residents watched helplessly as decades of toil turned to ashes. The inferno, one of nearly 200 reported in the city this year, consumed more than stalls and merchandise. It exposed the fragile underpinnings of Ethiopia’s disaster preparedness and the vulnerabilities of a rapidly expanding metropolis.

For millions, Mercato is more than a marketplace. It represents the heartbeat of a vibrant community of artisans, merchants, and traders. The recent fire illuminated the dangers of inadequate planning and insufficient safety regulations, revealing critical gaps in early warning systems, emergency response plans, and necessary infrastructure of a city that prides itself on being the diplomatic and political capital of Africa.

Addis Abeba, contributing nearly half of Ethiopia’s GDP, is racing toward megacity status, with its population projected to double to over 10 million by 2030. Yet this rapid growth brings a web of vulnerabilities threatening its preparedness against disasters, a concern exacerbated by unchecked urbanisation.

The panic induced by a series of earthquakes in the Awash Valley further exposes the city's unpreparedness. Disaster drills and simulations are nearly nonexistent, depriving millions of critical preparedness skills. A World Bank report paints a troubling picture. Close to 60pc of hospitals in Addis Abeba lack earthquake-resistant designs, a critical vulnerability in a city along the tectonically active East African Rift Valley. Other structural deficiencies — lack of reinforced emergency exits, unreliable electrical systems, and subpar medical storage facilities — could cripple operations during a disaster.

Natural calamities do not discriminate. From the densely populated capital to regional towns, floods, earthquakes, droughts, and fires wreak havoc at an alarming rate. The urban population across the country, projected to reach nearly 40 million by 2037, faces increasing risks from climate and environmental shocks. Yet disaster preparedness remains an elusive priority. In a country where infrastructure is expanding, and urban populations are booming, the costs of inaction should not be understated.

A World Bank diagnostic revealed that many cities and towns are ill-prepared to manage disasters. Cities like Adama (Nazareth), Bahir Dar, and Dire Dawa face escalating flood risks. Settled on the banks of Lake Tana, rapid expansion in Bahir Dar has encroached on high-risk flood zones, with over 25pc housing developments exposed to flooding. Flood-prone cities like Adama and Hawassa demonstrate the consequences of clogged and poorly maintained storm drains turning rainfall into catastrophes.

Weak infrastructure — poor roads, inadequate drainage, overloaded systems — aggravates these risks. Only 35pc of roads in urban centres are paved, impeding emergency vehicles and delaying evacuations.

Despite such looming threats, cities lack a centralised coordination unit for disaster response, a necessity for adequate preparation and emergency management. However, disaster risk management should not only be about fiscal efficiency. It should be a matter of social justice. Vulnerable populations often reside in the most at-risk zones, including informal settlements housing over 60pc of urban dwellers in cities like Mekelle and Addis Abeba. These residents suffer first when disaster strikes, yet have the fewest resources to recover.

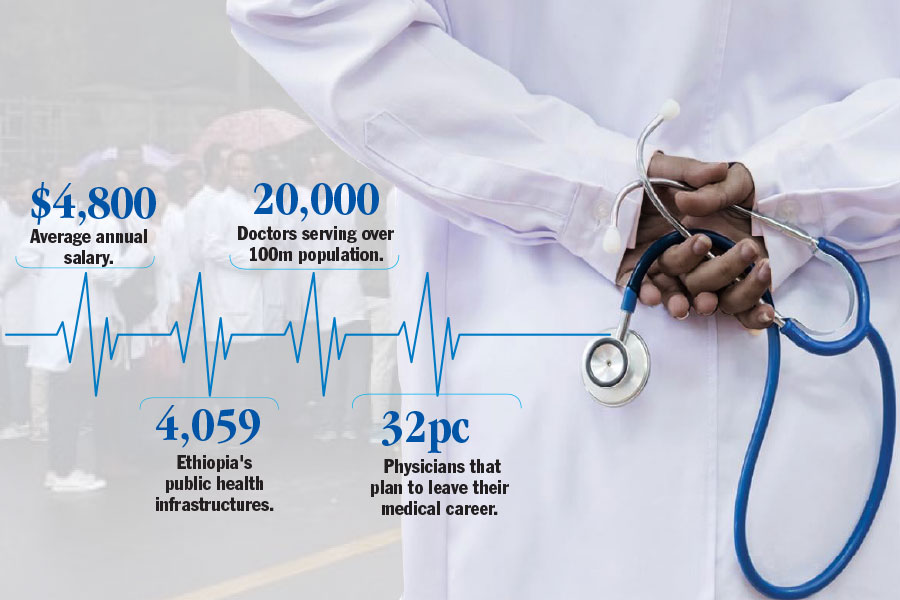

Hospitals in Addis Abeba are ill-equipped to handle sudden surges in patients. With an average of one hospital bed for every 1,500 residents, existing capacity is stretched thin. In times of crisis, this scarcity could prove catastrophic. Staff shortages compound the problem: over 70pc of healthcare workers surveyed reported limited training in mass casualty management or disaster response protocols. Healthcare spending per capita hovers around 23 dollars, a fraction of what is seen in developed economies.

Public spending on infrastructure and preparedness training is low on the priority list and overshadowed by immediate concerns like routine medical supplies and staffing. Yet failing to prepare for the unpredictable could result in far greater financial and human costs down the road.

However, Addis Abeba's vulnerabilities extend beyond healthcare. In central districts, the population density reaches up to 30,000 people per square kilometre, cramming a third of the population into only eight percent of the area. Unchecked urban sprawl consumes about 46pc of city land, much of it underutilised, escalating infrastructure delivery costs. This sprawl brings deteriorating public services, congested roads, and alarming urban blight.

Managing this expansion sustainably requires a robust regulatory framework and coordination across government agencies, elements largely absent today.

Water scarcity adds another layer of concern. Current water production is limited to over half a billion cubic metres a day, with nearly 37pc lost to inefficiencies and leaks. The city's per capita water distribution averages a meagre 40 litres daily, less than half its target of 110 litres. Many neighbourhoods, especially those with vulnerable populations, receive water only a few days each week. Escalating demand will stretch Addis Abeba's primary water sources even further.

Energy vulnerabilities compound the woes. While Addis Abeba boasts near-universal electricity access, blackouts and power interruptions are regular. The city relies heavily on an outdated grid, much of it over three decades old and operating below capacity. With an energy demand of 614mw, constituting around 42pc of the national peak load, the infrastructure is teetering.

Addressing these shortcomings requires enforcing building codes, conducting routine safety drills, and promoting hazard-resistant construction, especially in densely populated areas where over five million people reside. Many citizens in high-risk zones are not sufficiently educated about safety protocols, evacuation procedures, or emergency responses. Integrating disaster preparedness into the education system could prevent casualties and reduce damage in future incidents.

Disaster response efforts are currently slow and poorly coordinated, compounding devastation when crises occur. A centralised disaster management body with clearly defined responsibilities and streamlined communication could improve efficiency and response times. The federal government's contingency plan for this year, designed in response to multi-hazard risks, could be commendable. But, it also reveals a familiar gap between ambition and readiness.

The plan has a 295 million dollar budget across critical sectors like agriculture, health, education, food, and shelter, yet gaps emerge quickly.

This year's rainy season brings grim projections of over three million people likely affected, with nearly 900,000 expected to be displaced in regional states like Amhara, Tigray, Oromia, and Somali. The food cluster needs 91.6 million dollars to feed the displaced, but not a single dollar has been earmarked as of June. The education cluster expects over 1,400 schools might be affected by flooding, potentially disrupting education for more than a million children. Despite this, a 44 million dollar budget for protective measures is unmet.

Although the contingency plan represents the federal authorities' best attempt at a cohesive strategy, actual readiness demands more than paperwork. It requires rapid mobilisation of funds, resources, and people, all of which are presently in short supply. For many in risk-prone zones, the season will not only be about weathering hard times but also about surviving another year of unmet promises and underfunded plans.

The economic argument for investing in urban resilience cannot be more evident. A World Bank report estimates that Ethiopia has sustained average annual losses of over 400 million dollars due to natural disasters since 1983. Investment in disaster preparedness could reduce these costs by up to 30pc. For a country where over 20pc of GDP is tied to urban activities, such savings could translate into billions of Birr retained in productivity.

As the government commits nearly 40 billion Br (approximately 375 million dollars in last week's central bank exchange rate) to infrastructure projects, it should also prioritise adequate funding for disaster management programmes. This includes modernising essential services like firefighting and emergency medical services, ensuring the city is better equipped to handle future crises.

PUBLISHED ON

Oct 26,2024 [ VOL

25 , NO

1278]

View From Arada | Apr 17,2021

Fortune News | Nov 21,2018

Radar | Oct 19,2019

Viewpoints | Mar 30,2019

Viewpoints | Feb 20,2021

Fortune News | Mar 09,2024

Fortune News | Jun 17,2023

Radar |

Editorial | Sep 30,2023

Viewpoints | May 27,2023

Photo Gallery | 178627 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 168820 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 159655 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 137089 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

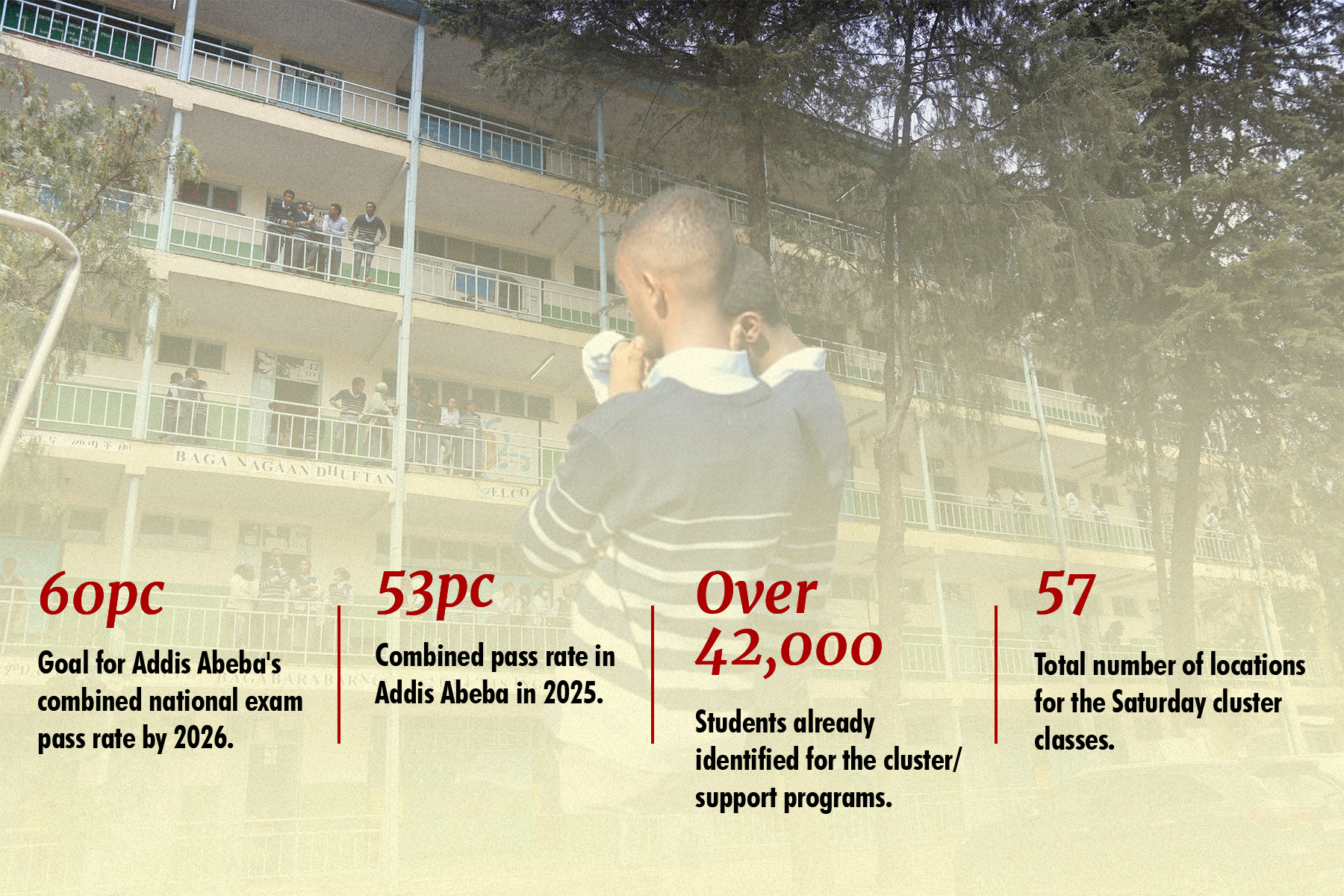

Oct 25 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

Officials of the Addis Abeba's Education Bureau have embarked on an ambitious experim...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The federal government is making a landmark shift in its investment incentive regime...

Oct 29 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) is preparing to issue a directive that will funda...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A community of booksellers shadowing the Ethiopian National Theatre has been jolted b...