Featured | Dec 29,2018

Small business owners in Merkato, Africa’s largest open market space, were dumbfounded by the sudden gridlock of transactions two weeks ago. It was in the aftermath of a consequential decision by federal authorities to cap imports of a long list of goods. Imposed three weeks ago by the Ministry of Finance and central bank officials, the fateful decision has added a burden to the already depressed business mood in the city.

The lively streets were idle - the usually vibrant young men now sluggish, leaning on vehicles and fiddling with their hair. Shops were open but with few products scattered on their shelves. Shopowners, salespersons, intermediaries and porters whose livelihoods depend on these transactions had anxious faces, perplexed about what lies ahead.

Seid Mohammed works in the import business around Anwar Mosque, the hub for the retail and distribution of carpets. He imports and distributes mats from Turkey and Dubai.

Turkish rugs cost almost double their price three weeks ago. With the rising prices and an average monthly rent of 30,000 Br, importers such as Seid have found themselves unable to keep up with overhead costs. They are unable to restock. He expects prices to skyrocket, for no domestic alternative meets the quality standard and his customers’ expectations.

“I’ve sent three of my salespersons home,” Seid told Fortune.

What worries him even more is the indefiniteness of the decision by the authorities. Seid fears this might result in supplies shortage, eventually forcing him to close his shop.

The State Minister for Finance, Semerita Sewasew, signed off what is now an unpopular edict among importers. Merchandise from abroad - from human hair to chewing gum and vehicles to furniture - would not be granted access to letters of credit. Central bank governors followed this up, ordering all commercial banks not to provide foreign exchange commitments to these items deemed less of a priority. The State Minister attributed the ban to a “decision made by the macroeconomic committee,” chaired by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD), to allocate foreign currency to essential imports.

Solomon Desta, vice governor of the central bank, justifies the move as a means to stabilise the foreign currency reserve.

“The ban will stay in effect until the shortage of foreign currency is resolved,” he told Fortune.

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) sits on a record-low foreign currency reserve. According to data from the IMF, it has plummeted to less than a billion dollars, enough to cover 20-day imports. The IMF warns that next year’s prospect will be grimmer, forecasting that the reserve will diminish to less than two-week imports. It is devastating news for an economy with an import value that is four times larger than the four billion dollars in earnings from exports.

Many in the private sector find the justification by the authorities unconvincing, including executives of Debub Global and Berhan banks.

Tesfaye Boru, president of Debub Global Bank, sees the decision’s rationale somewhat differently. It is a policy move targeting the parallel forex market.

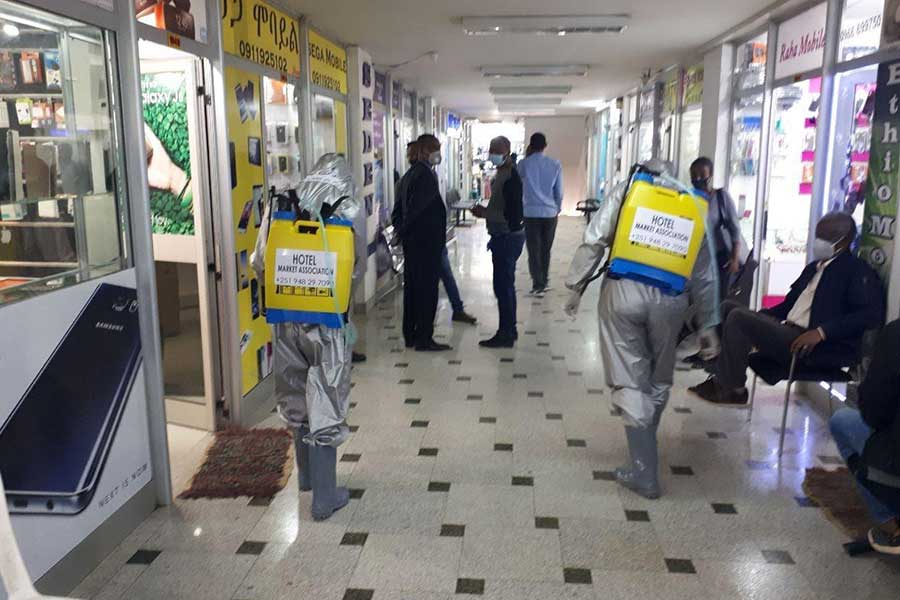

Hair, makeup and nail care salons face the sudden scarcity and skyrocketing prices of beauty products.

It has been going out of hand, exhibiting over a 50 Br margin compared to the official exchange rate of 53 Br for a dollar a few weeks ago. The Birr continued to lose ground against a basket of major currencies, including the dollar. It was exchanged for 53.9 Br last week, almost half the amount the parallel market offers to those with the greenback. The parallel market seems to thrive in the face of official crackdowns, including arrests of individuals suspected of doing business in the “black market.”

The decision to cap the imported items will not dent the foreign currency reserve position, according to Tesfaye.

The voice from economics pundits reinforces the official view of capping imports and encouraging import substitutions. For commodities such as packed foods that can easily be substituted locally, the decision has come too late, believes Tadele Ferede, associate professor of economics lecturing at Addis Abeba University.

“Contrary to the government rationale, the ban benefits domestic producers,” Tadele told Fortune. “The amount of foreign currency the government saves is insignificant.”

The data could have informed his view on how much all the items State Minister Semerita banned are worth. They had an aggregate value between 600 million to 900 million dollars in the three-year average before last year. This amount represents five to six percent of the average total imports. For every 30 dollars Ethiopia exported two years ago, it spent over 90 dollars to import petroleum (1.24 billion dollars), gas turbines (532 million dollars), planes, helicopters and spacecraft (406 million dollars), wheat (320 million dollars) and packaged medicines (317 million dollars).

Alemayehu Geda, professor of economics at Addis Abeba University, believes the government had no choice but to make such a drastic decision. He likened the move to what South Korea did following a similar crisis.

From the products on which import cap is imposed, vehicles are the ones that can be attributed to significant import bills, says Girum Tsegaye, Berhan Bank’s president.

The unavailability of forex and long waiting lists to get permits from the central bank push importers to buy forex at higher rates in the parallel markets, which they eventually compensate for, raising the price of their imported goods. In contrast, exporters ship out commodities at lower prices than the international market offers to get their hands on foreign currency, which, more often than not, goes towards parallel import activities. Exporters are allowed to retain 30pc of the value of goods they sell in the global market.

Girum noticed car importers open letters of credit for nearly half a million dollars to import 20 cars. But, a higher value goes to the manufacturers, causing an imbalance between import and export bills.

Halel Car Imports is one of the companies affected by the ban. It has been in business for nearly two decades with three branches, importing cars from Dubai and Europe.

Confounded by the sudden change, the managers are attempting to adjust.

“We’re planning to shift our business model to electric cars,” said Moges Negash, the marketing manager.

Electric vehicles are not included in the items suspended from accessing forex. With a growing number of car importers and changing their business model to electric cars, companies such as Green Tech Africa face competition. A subsidiary of Shemu Group, a conglomerate comprising 15 companies, Green Tech Africa was incorporated with 1.3 billion Br capital.

Expanding its presence in regional states and other African countries, Green Tech plans to import 5,000 electric cars in the coming five years, welcoming the competition with open arms.

Furniture importers are also trying to adjust, shifting their business models.

Solina Sofa, a furniture importer since 2009, looks to make ends meet with locally manufactured products. The Manager, Yohannes Sisay, is determined to stay in business with local substitutes despite clients’ concerns over quality issues. The push to substitute imported items with domestically manufactured goods could be an inadvertent outcome of the policy to cap imports.

For Assefa Admassie, associate professor of economics, Ethiopia’s export bill has never been greater than the import bill.

Governments use three alternatives to fill this gap: export, remittance, and official loans and grants. However, export revenues are critically low, and a lot of the remittances are not transferred through formal channels. Loans and grants have been discontinued owing to the prevailing political situation. The alternative is prioritising the essential imports, banning the less important, and substituting others with domestically produced items, said Assefa.

“The ban will have a positive outcome if the government provides incentives and make domestic producers fill the gap,” Assefa told Fortune.

Locally made products like laundry detergents, commonly known as “largo”, have sustained price spikes. The cost of a bar of Nisa Soap, an imported fragrant body wash in high demand, has jumped by 20 Br from 55 Br in three weeks.

With a 150,000 Br initial capital, Bekas Chemical Plc has been manufacturing soaps, detergents, cosmetic products and packaging materials since 1998. It has 50 distribution outlets across the country with three branches in Addis Abeba, Adama and Meqelle. It is the sole provider of detergents for major hotel brands such as Skylight and Sheraton Addis hotels.

“It’s a great opportunity to boost our market,” said Anteneh Yemaneh, CEO of Bekas Chemicals. “The government has done the right thing.”

He believes importing soap and detergents was unnecessary as these could be substituted with local products.

Despite his endorsement of the authorities’ move, Bekas Chemicals faces challenges getting a synthetic chemical surfactant (LABSA) used to manufacture industrial detergents. Allied Chemical Plc, 90Km from the capital, is the sole plant that provides LABSA for soap manufacturing factories. Bekas is not getting adequate chemicals. They have requested the central bank to allow them to open a letter of credit to import the inputs.

Confounded car importers are attempting to adjust, shifting their business model to import electric vehicles.

However, not every product can be manufactured locally. The import ban has begun to affect the livelihood of people. Business owners are sending their employees home out of fear of plunging business.

The beauty industry faces uncertainty with limited room for adjustments following the unprecedented move. The scene at the Morning Star Mall near Bole Medhanealem illustrates the impact caused by uncertainties. Among multiple cosmetics and human hair retailer shops is Betty Beauty Salon.

It is a hairstyling, makeup and nail care salon on the second floor of the building. Bethlehem Abebe opened her place there five years ago after having two years of experience as a hairdresser. She went to Merkato to restock artificial nails, one of the main products her clients often demand. She could not find them in any of the shops. She attributed the sudden scarcity to the hoarding of products by importers.

“I don’t know how to sustain the business if things continue like this,” she told Fortune.

Subsequently, she decided to lay off five of her eight employees, which she says was frustrating.

Zemi Spa is another business in the same building offering eyelash and wax services, with an average of four clients visiting daily. Tenbit Esayas, the manager, shares Bethlehem’s concerns. With five employees working for her, Tenbit worries that she will be forced to let go of some of them and eventually close the business if products remain unavailable.

Importers with fully stocked warehouses consider themselves lucky about the timing. However, uncertain about the process and time it will take to get letters of credit in the foreseeable future, they are forced to raise prices on the existing stocks to shield themselves from cost build-up in the future. Synthetic wigs, widely used in beauty salons for braids, have almost doubled in price from 95 to 160 Br. According to hairdressers, a person uses at least four pieces of synthetic wig at a time.

Dir Tera Building is 100 meters north of the Anwar Mosque, with an average monthly rent of 15,000 Br for a four-metre square shop on the first floor. The middle-aged women in the building, selling cosmetics and sanitary products, were apprehensive by the market lassitude, fearing that they might have to return to the Arab countries if the market continued its descent.

The cosmetics and fragrances distributor, Yared Abebe, saw his business frozen following the ban. The recent order has left distributors like him in a dilemma on whether to raise prices or wait.

The indefinite ban has led retailers to raise the prices of imported commodities. Nearly 3,000 Br was added to whiskeys following the announcement. Alemayehu, the economics professor, believes that the Ministry of Finance should not have made an official announcement to the public, attributing the hoarding of products to fear and uncertainty.

However, trade authorities warn that they will take administrative measures to sanction businesses that create volatility in the market. Teshale Belihu, state minister for Trade & Regional Integration, says there will be a controlling mechanism to discipline the market.

“We’ve instructed all regional states and city administrations to control the rise of prices,” Teshale told Fortune.

PUBLISHED ON

Nov 05,2022 [ VOL

23 , NO

1175]

Featured | Dec 29,2018

Featured | Jul 25,2020

Agenda | Sep 22,2024

Radar | Apr 25,2020

Fortune News | May 17,2025

Commentaries | Jul 31,2021

Agenda | Dec 14,2019

Fortune News | Jan 01,2023

Agenda | Aug 04,2024

Fortune News | Jul 09,2022

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 5 , 2025

Six years ago, Ethiopia was the darling of international liberal commentators. A year...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jun 14 , 2025

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars...