Aug 3 , 2024

By Matias Assefa

Ethiopia is diving into uncharted financial waters with its government's decision to free-float the Birr. This could lead to long-term benefits such as increased foreign currency from legal remittances, reduced capital flight, and less contraband. However, the certainty of these benefits — and the risks they entail — make this an intriguing development to watch unfold, writes Matias Assefa (matias.assefa@gmail.com), an economic and business analyst based in Addis Abeba.

The federal government’s recent decision to allow the market forces of supply and demand to determine the foreign exchange rate of the Birr marks a radical shift in the country’s economic strategy. A central element of the government’s “Home-grown Economic Reform Plan,” the policy move has been long anticipated but also contentious, evidenced by the longstanding disagreements between Ethiopia and influential financial institutions like the IMF and World Bank.

The policy seeks to enhance international competitiveness, improve the trade balance, ease debt burdens, and stabilise the macroeconomy. However, this transition is fraught with potential pitfalls and over-optimistic expectations.

The government’s confidence in the policy’s long-term advantages should be balanced against the immediate hardships it imposes, particularly on the poor and working-class citizens. With 70pc of the population experiencing multidimensional poverty and already strained by high living costs, further aggravating factors could push them to a breaking point.

Ethiopia has secured over 10 billion U.S. dollars from the IMF, World Bank, and other development partners to aid adjustments and mitigate the anticipated pain. The government has pledged to strengthen social safety nets, raise wages, and partially subsidise fuel prices.

Ethiopia has struggled with its exchange rate policy for years, trying to balance between free-floating, fixed, and pegged exchange rates. In its recent history, the country followed a managed-float exchange rate with strict capital controls. This hybrid approach has led to neither price stability nor a stable foreign exchange market.

Persistent current account deficits have resulted in balance-of-payments problems, depleting foreign reserves, and escalating external debt. Chronic shortages of hard currency have impeded exporting and manufacturing sectors, stifling economic growth and exacerbating unemployment. The overvalued exchange rate has also fueled a flourishing illegal parallel market for U.S. dollars.

The IMF argues that the Birr has been overvalued by 20pc to 40pc, urging policymakers to depreciate the exchange rate, hoping to rectify these macroeconomic distortions. However, its approach addresses symptoms rather than underlying market failures and structural rigidities.

For a start, even if Ethiopia adjusts its nominal exchange rate, there is no guarantee that the real exchange rate will align as intended. During the 14 years since 2006, although the nominal effective exchange rate was devalued by an average of 4.5pc annually, the real effective exchange rate appreciated by five percent yearly. Inflation differentials with major trading partners dictated this phenomenon, negating any competitive advantage.

Floating the exchange rate clean may not eliminate the parallel market premium, as shown by countries like Nigeria.

The idea that depreciating the exchange rate will boost exports by making them cheaper and reduce imports by making them more expensive is also oversimplified. Ethiopia’s essential imports, such as capital equipment, fuel, medicine, and fertilisers, are not easily cut back without severe socio-economic repercussions. Its export portfolio, concentrated in primary products like coffee, cannot be quickly expanded in value, maintaining the large trade deficit.

Strictly speaking, low domestic savings and higher inflowing than outflowing investments are behind Ethiopia’s trade deficit. Enhancing productive capacity through technological and structural reforms is more critical than trade policy adjustments.

Historical precedents also suggest that monetary reforms alone do little to improve international competitiveness without robust, productive capacity, high-quality human capital, and innovation. The contrasting fortunes of Argentina in the early 2000s and modern-day China illustrate this point.

Several risks accompany the shift to a free-floating exchange rate.

Depreciation of the Birr could stimulate inflation due to higher import prices and subsequent wage demands. With a substantial amount of foreign currency-denominated debt, a weaker Birr increases the debt burden. Speculative investors could also dominate the forex market, increasing exchange rate volatility and business uncertainty.

The policy departure further exposes the Birr to speculative attacks, potentially triggering a rise in actual and expected inflation.

At least in the immediate term, the new exchange rate regime might exacerbate macroeconomic instability, undermining some of its intended benefits. Ideally, Ethiopia should have adopted a clean-floating exchange rate when inflation and the parallel market premium were under control, stabilising at modest levels, and domestic exchange and financial markets were sufficiently developed.

However, the government believes this policy shift will generate long-term benefits, such as increased foreign currency from legal remittances, reduced capital flight, and diminished contraband. The policy change could also promote exports, attract foreign investments, and enhance economic freedom.

Yet, the certainty of these benefits remains questionable.

Will Ethiopia weather the inevitable volatility in the exchange rate and the inflation risks from potential currency overshooting?

The hope is that it will, but only time will provide a definitive answer.

PUBLISHED ON

Aug 03,2024 [ VOL

25 , NO

1266]

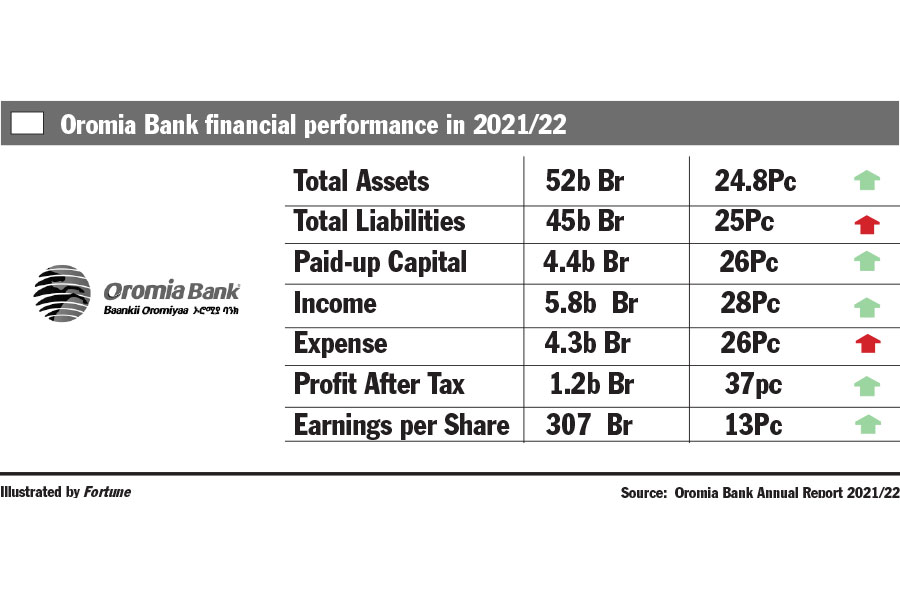

Fortune News | Jul 30,2022

View From Arada | Apr 02,2022

Fortune News | Sep 30,2021

Fortune News | Jul 15,2023

Fortune News | Jul 13,2020

Fortune News | Apr 19,2025

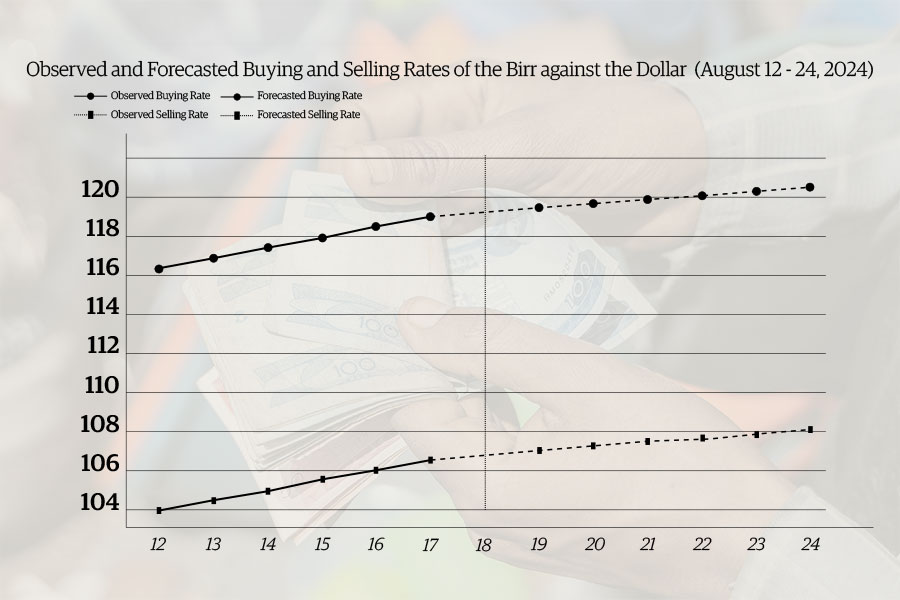

Money Market Watch | Aug 18,2024

Fortune News | May 07,2022

Radar | Mar 13,2021

My Opinion | 131548 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 127903 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 125879 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123510 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jun 14 , 2025

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars...

Jun 7 , 2025

Few promises shine brighter in Addis Abeba than the pledge of a roof for every family...

Jun 29 , 2025

Addis Abeba's first rains have coincided with a sweeping rise in private school tuition, prompting the city's education...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Central Bank Governor Mamo Mihretu claimed a bold reconfiguration of monetary policy...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal government is betting on a sweeping overhaul of the driver licensing regi...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Gadaa Bank has listed 1.2 million shares on the Ethiopian Securities Exchange (ESX),...