Fortune News | Feb 02,2019

Dec 25 , 2021

By Yehualashet Tamiru , Selam Kibret Shuma

As the old adage goes, maternity is a matter of fact, but paternity is always a matter of opinion. With the mother, the sole fact of birth establishes maternal filiation. Paternity is a whole other story, write Yehualashet Tamiru Tegegn (yehuala5779@gmail.com), lawyer, consultant and researcher, and Selam Kibret Shuma (selam.kibret@gmail.com) lawyer, gender expert and conflict transformation and peacebuilding adviser.

Family is the most important institution of human society. It plays a vital role in all societies' socio-cultural and economic developments. As a result, nations of the world are entrusted with special duty to preserve the family and thereby the society and its values. The protection of a family is not only limited to the constitution of a nation. Above that, international conventions also impose an obligation to protect the institution, at least on those states that ratified them. One of the critical aspects of family relationships is filiation.

Filiation may be understood in two senses, according to Marcel Planiol, one of the most influential jurists. In the wider sense, it is taken as descent in the direct line, which includes the entire series of intermediaries who link a given person to this or that ancestor, however distant they may be. But in legal terminology, in a narrower sense, the term has assumed a much more restricted meaning in which filiations extend exclusively to the immediate relationship of a father or mother and hence, it applies to the blood relationship of first degree in the direct line.

There is an old age saying that maternity is a matter of fact, but paternity is always a matter of opinion. With the mother, the sole fact of birth establishes maternal filiation. Paternity is a whole other story.

The revised Federal Family Code recognises three modalities for ascertainment of paternity. The first is paternity through legal presumption. As a matter of rule, a child conceived or born in wedlock has the husband of the mother as his father. Since the duration of pregnancy cannot specifically be determined, some countries have adopted a law fixing the time for a period of pregnancy while others leave the matter to be established by the evidence of the parties concerned.

Following the French system, the Ethiopian legislature has strictly fixed the time within which a child stays in his mother’s womb. When a child is born more than 180 days after the celebration of the marriage and less than 300 days after its dissolution, it will be considered as having been conceived in wedlock.

The second mechanism is an acknowledgement of the child by the father. It is a procedure whereby a man declares that he considers himself the father of a particular child merely conceived or born. However, the law does not allow for the acknowledgement of every child. It is only when a child does not benefit from the presumption – as we have discussed above - that the acknowledgement comes into the picture.

The third mechanism is the ascertainment of paternity through judicial declaration. Where a child has neither a presumptive father nor a self-acknowledged one, his paternal affiliation may be judicially declared if his mother has been, among other things, the victim of raped or abduction.

Perhaps on top of these legally recognised forms of ascertainment of paternity, there is another widely used form: DNA tests. Nowhere under the revised Federal Family Code of Ethiopia is DNA mentioned as a mechanism of verifying paternity. However, as a matter of practice, there are numerous instances where both the litigant parties and the court can make use of it.

Despite no clear recognition in the law, there is a precedential cassation decision that permits the use of DNA. On top of this, the child has the right to know their father, as part of the best interest of the child, which could be cited as a compelling legal reason to justify the use of DNA.

In one case at the Federal Supreme Court Cassation, it was decided that the person who has asked for the DNA test should bear its cost. This is an extension of the legal duty that whoever files the suit has the burden of proof on their shoulders. On the face of it, it appears that there is nothing wrong with this decision. Nevertheless, it’s one of the most painful decisions for many mothers to make.

DNA is seen as a truth machine with very few and far apart errors providing definitive proof as to the fatherhood of the person. As the number of births to unmarried women continues to increase, the role of DNA in the ascertainment of paternity is very crucial.

It is impossible to rule out the possibility of requesting DNA tests by someone who has had fatherhood established under the modalities described above and want to disprove his fatherhood by DNA test. However, most of the time, it is the mother that requests verification. This could be to secure alimony, which means that these women are already in dire financial circumstances.

Ethiopia's laws seem to adopt need-based alimony rather than gender-based. Gender is not taken into consideration, just who is comparatively better off. Usually, men earn more money while women have a higher chance of being stuck at home due to prevailing socio-economic inequalities.

To make matters worse, DNA has to be processed outside of the country. The cost, over 20,000 Br, is thus prohibitive even for a person living a decent life, let alone for struggling mothers. Consequently, the mothers are forced to stay in the legal proceeding for a long time until they can raise the fund or find a third party to cover the expenses.

Since alimony is only applicable in prospective than retrospective cases, as it is intended to fill the needs of the future, not to compensate for the actions of the past, the whole process could be moot. As it is currently understood, the very purpose of alimony is the prevention of unfairness by compelling the father to share part of the economic burden of the mother in raising their child. Nowhere is it indicated that the alleged father should provide provisional maintenance to the mother until the conclusive DNA test comes back.

The cassation bench that set this precedence should have thus provided such a decision to avoid well-intended but detrimental interruption in the existing father-child relationship to achieve some level of predictability and fairness in the outcomes. Because of this painful decision, many women are left helpless and their children fatherless.

PUBLISHED ON

Dec 25,2021 [ VOL

22 , NO

1130]

Fortune News | Feb 02,2019

Fortune News | Jul 18,2021

Fortune News | May 23,2020

Radar | Apr 15,2023

Fortune News | Apr 30,2021

Verbatim | Nov 26,2022

Fortune News | Dec 17,2022

Fortune News | Aug 03,2019

Fortune News | Jun 27,2020

My Opinion | Jan 18,2020

Photo Gallery | 178648 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 168842 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 159676 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 137093 Views | Aug 14,2021

Commentaries | Oct 25,2025

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

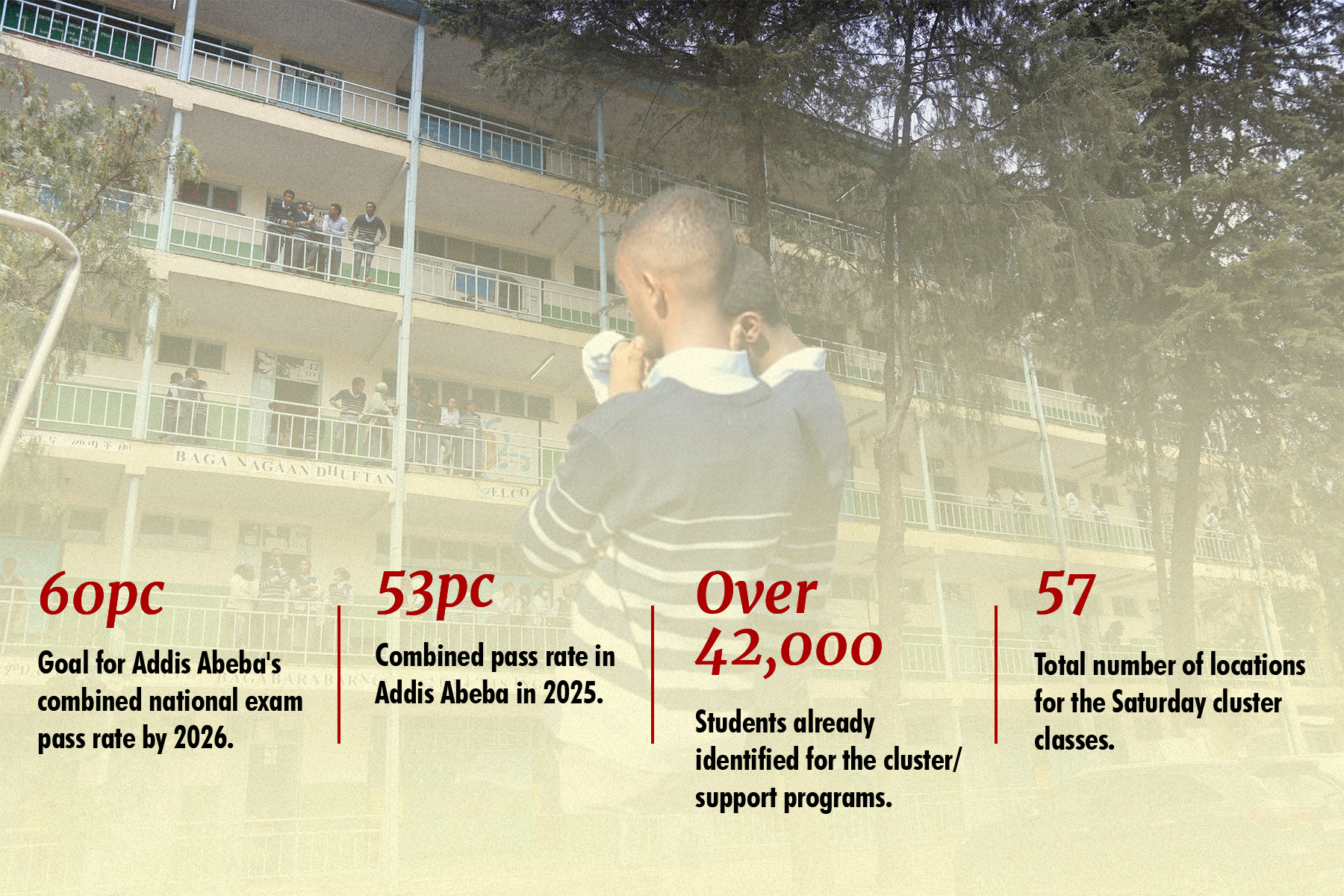

Oct 25 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

Officials of the Addis Abeba's Education Bureau have embarked on an ambitious experim...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The federal government is making a landmark shift in its investment incentive regime...

Oct 29 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) is preparing to issue a directive that will funda...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A community of booksellers shadowing the Ethiopian National Theatre has been jolted b...