Nov 9 , 2019.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD), in his address to members of parliament last month, gave what was an unambiguous signal that his government is determined to hold the national elections in 2020, as constitutionally mandated. It is telling that his statement was given in an answer posed by an MP who had expressed reservations whether the election can be held in the current security reality. That informs most of the debate on the issue of the coming elections.

The Prime Minister put on a brave face, conceding that there are security problems. But he chose to take a different perspective than the usual reluctance to commit himself on the issue, despite a firm decision by the Executive Committee meeting of the party he chairs, the incumbent EPRDF.

He could not have been more logical, acknowledging that there will always be problems. Going ahead and not backtracking on the democratic discourse is better than waiting for the uncertainties to settle.

It was wise for him to see that the reward of an electoral mandate is worth the high risk of pursuing the electoral road even in a less than ideal situation. The unclear procedural hurdle of postponing national elections, the lack of consensus to extend it and the potential for a crisis of legitimacy that could result are all strong reasons that may have made up his mind in the end.

The disturbances in several places in the Oromia Regional State not long after his speech justified both the concerns of those who raised the question and perhaps, more importantly, the acute need for an electoral mandate. A state without a legitimate mandate to use lawful force to ascertain law and order can find it extremely difficult to tackle the polarisation that is bordering on lawlessness.

Indeed, the challenges are many. Even though a law governing political parties was passed in June, it has not been met with a welcome gesture by a large bloc of the opposition. A number of them are expressing their displeasure at the new rules by which the number of petitions required for registration to operate nationally is raised to 10,000 from the previous 1,500 and for regional parties to 4,000, from 750.

Understandably, not few of the parties find this a high bar to meet and could drop out of the race. Under the current circumstances prevailing in the country, leaders of these opposition parties argue the law limits citizens’ rights to organize freely, while the state contends that the proliferation of parties is more of an impediment to democracy. The thinking behind the argument in the latter is that too much of a choice for voters limits their ability to pick their preference easily. It is no less flimsy in its power of logic.

In the midst of these contentions though and the persistent flare-ups of violence around the country, there is an understandable concern that it may not be possible to campaign freely around the country. Many are worried that the passion unleashed during the electoral contests may flare up, fueling conflict in an otherwise delicate situation. It is a fear grounded on and informed by experience.

Leaving this debate aside, once a decision is taken, and there is the political will to go ahead with the elections, the focus should turn to the National Electoral Board of Ethiopia (NEBE), the only federal agency tasked to administer national, regional and local elections.

Unfortunately, this has been one of the constitutional institutions whose legitimacy and credibility was challenged throughout the electoral history of this country since its formation in the mid-1990s. The partiality of its board members and the chiefs to the incumbent has always been a battleground for the contending political parties and their respective supporters.

It was seen as a refreshing change of course when parliament confirmed the Prime Minister’s nomination of Birtukan Mideksa, a former opposition politician, to head the National Electoral Board. Returning from exile, she was also tasked with restructuring the organisation - one of the most significant reforms Abiy's administration has undertaken thus far. Along with similar reforms in the judiciary and law enforcement, hopes are high that these will go a long way in preparing the conditions that can facilitate a reasonably credible election.

While this is all commendable and there are signs that the Board has been hands-on in reorganizing and strengthening its institutional capacity, the thing that is in short supply is time. There are only six months left if the elections are to be held in May next year according to the Constitution’s stipulation. It determines, in no uncertain terms, that the term for the federal legislative body where the executive comes from is for five years.

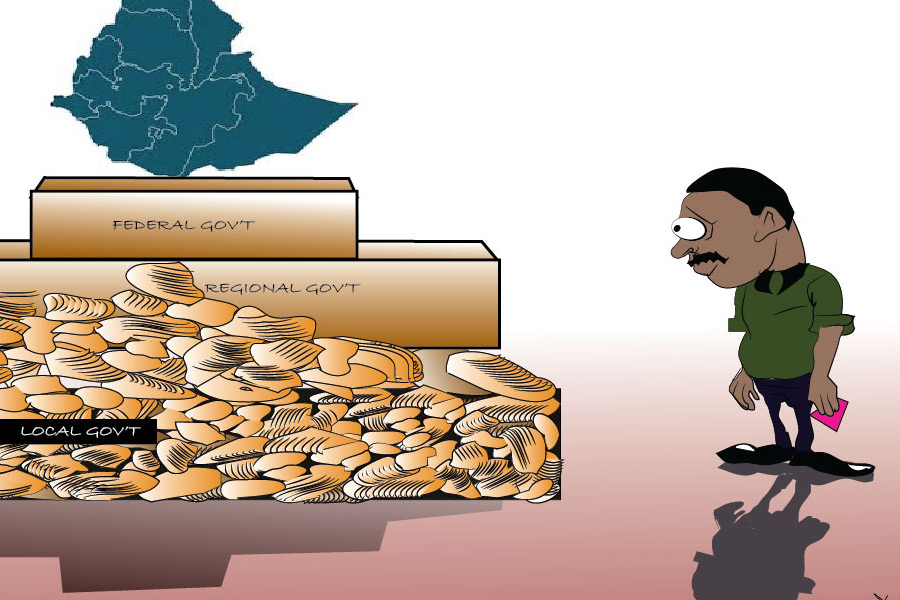

Six months is a very short time compared to the enormity of the logistical tasks involved. Ethiopia is such a large country with challenging topography and limited transportation infrastructure, even the straight forward task of distributing election documents such as ballot papers and boxes is not an easy challenge. It is an enormous logistical undertaking. It involves 547 constituencies and over 45,000 polling stations spread all over the country. Close to 37 million citizens cast their votes in the elections five years ago. It is expected to grow.

There must be preparations being undertaken by the Electoral Board. At this point in the process, however, there is not a whole lot of activity that can be observed from the outside. There is little engagement with the voting public. This naturally raises the question whether, in the debate about postponing the elections, the vital matter of the logistical challenge has been underestimated.

The previous national elections have all had various levels of questions on their credibility. However, the technical and logistical performance has always garnered high praise even by the most critical voices of the process. In the upheaval of the enormous changes that have happened since the last elections and the reorganisation the Board has gone through, how much institutional memory may have been lost, one wonders.

Could that lead to underestimating the challenges?

That the voting public is yet to know the official election timeline at this point in the process should be alarming. No less worrying should be the almost complete lack of any semblance of campaigning by the contending parties.

Will this be another lost opportunity for democracy and credible elections once again?

The formality of having elections is not by itself a guarantee to a democratic order. After all, even the Dergueconducted elections of sorts. However, a democratic society always has elections as a tested mechanism for the expression of popular choice. Exercising the right to choose leaders is a distinguishing feature of a democratic state. If this culture is to take root, as the Prime Minister rightly pointed out, it has to be exercised despite the hurdles.

Would it not be a reversal for that exercise to fail because of logistical unpreparedness?

PUBLISHED ON

Nov 09,2019 [ VOL

20 , NO

1019]

Year In Review | Jan 02,2024

Radar | Aug 17,2019

Viewpoints | Jan 01,2022

Radar | Jan 01,2024

Fortune News | Dec 07,2019

Viewpoints | Nov 30,2019

Commentaries | Jan 29,2022

Election 2021 coverage | Mar 01,2020

Editorial | Dec 10,2018

Radar | Apr 27,2025

My Opinion | 131458 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 127810 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 125791 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123426 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jun 29 , 2025

Addis Abeba's first rains have coincided with a sweeping rise in private school tuition, prompting the city's education...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Central Bank Governor Mamo Mihretu claimed a bold reconfiguration of monetary policy...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal government is betting on a sweeping overhaul of the driver licensing regi...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Gadaa Bank has listed 1.2 million shares on the Ethiopian Securities Exchange (ESX),...