Established in 2019, East Africa Plastic Centre operates at a 30pc capacity due to a lack of working capital. Its managers' application for a loan of 100 million Br submitted five months ago remains unapproved by all the banks they approached.

Dereje Weldeamanuel, the general manager, attributed the dry spell to a loan cap.

"We're in survival mode," he said.

Partly, his company is a victim of a little-heeded shift in monetary policymaking. A consequential reorientation of the central bank's goal, which focuses on inflation targeting and price stability, has Governor Mamo Mehiretu imposed a loan cap policy on commercial banks. It may have moderate success in taming inflation, reducing the year-on-year (YoY) headline inflation by 2.2 percentage points to 28pc by the end of 2023.

However, the broader economic fallout tells a depressing story that a one-size-fits-all approach may be too blunt an instrument for the evolving financial sector. The loan cap that puts new entrant banks in troubled waters has created a domino effect. Businesses are struggling, share prices are falling, and investors' confidence is waning.

A new wave of third-generation (3G) commercial banks that emerged over the past three years, aspiring to reshape the financial scene, are particularly impacted. Yet, these institutions are constrained by stringent regulatory measures meant to curb inflation but inadvertently stall their growth.

Banks' total loans and advances grew by 24.3pc reaching a total of 1.8 trillion Br by June 2023, attributed primarily to the sectors of manufacturing, domestic trade and services, and consumer banking. The credit distribution to various economic sectors is notably diverse, with significant loans extended to manufacturing (23.2pc), domestic trade and services (20.7pc), and exports (15.7pc). There has been a shift towards increased private sector lending, with private sector credits constituting a majority (55.9pc) of the total banking sector credit by 2023.

Total deposits increased by 24.6pc, amounting to 2.1 trillion Br during the same time, a growth supported by upsurges in savings and time deposits. The share of total deposits as a percentage of GDP was 24.8pc by June 2023, indicating a substantial liquidity pool within the banking sector.

The authorities appear to be determined to redirect this pool to where they want. A mandatory purchase of annual bonds from state-owned banks and a uniform 14pc annual loan growth cap, which remains unchanged despite measures announced by the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) in August to bring inflation under 20pc.

Executives from about 10 of these banks — from Geda to Goh Betoch and Tsehay, Ahadu as well as from Amhara to ZamZam, Sidama and Shabelle — have raised concerns. In an appeal to regulators, they argue that the cap unfairly lumps them with long-established banks, ignoring the nascent stage of their development. The cap is particularly painful as several of them - Tsehay, Geda, Amhara, Ahadu, and Goh Betoch- reported losses in the last financial year.

These young banks are wrestling with the dual challenge of restricted loan growth and the high costs of setting up branches and staffing. The environment delays their path to profitability. They are increasingly focusing on short-term loans and alternative revenue streams like service charges and guarantees to stay afloat. However, their senior executives worry that such a strategy compromises the quality of customer service, a bedrock of their long-term business models, due to the heavy initial investments in infrastructure and staffing.

The loan cap also prevents companies from attracting new shareholders and meeting the minimum capital requirements of five billion Birr set by the central bank, which will expire in 2026.

Hijra Bank, a Sharia-compliant finance institution, illustrates a unique but similarly unsteady position. It mobilised 4.84 billion Br in savings last year, an impressive 263.9pc increase from its inaugural year, and reported a net profit of 27.8 million Br for 2022/23. Despite these gains, the uniform loan cap applies as stringently to them as to commercial banks, leading to scaled-back expansion plans. The Bank's ambition of reaching 100 branches this year was short by 89pc, running only 82.

“The disparity between loans and deposits created a management challenge,” said Dawit Keno, president of Hijra Bank, noting that the cap restricts their ability to invest surplus deposits in Sharia-approved financial instruments like Murabaha and Mudarabah. It is not alone.

Sidama Bank, which transitioned from a rural microfinance origin, faces similar constraints. The institution started as the Sidama Rural Women's Credit & Saving in 1994 before becoming a full-fledged microfinance institution four years later.

With a paid-up capital of 575 million Br and a subscribed capital of 1.45 billion Br, it has explored alternative revenue streams such as foreign exchange generation and guarantee bonds. Yet, according to Tadesse Hatiya, president of Sidama Bank, these methods are "not as satisfactory" compared to traditional interest income. A competitive disadvantage against more established banks, the loan cap indirectly affects Sidama's profitability and potentially hinders the future share it wants to float to the public.

"We've limited branch expansion and staff hiring," he said.

Sidama Bank posted a profit of 63.9 million Br last year, with loans and advances totalling 613.3 million Br. Nevertheless, Tadesse blamed lower interest income due to the cap that directly impacted their bottom line.

Another interest-free finance institution transformed from a microfinance operation in the Somali Regional State, Shabelle Bank, also faced these harsh realities. It reported a profit of 19.84 million Br last year but has seen a marked rise in profit taxes and operational costs. It has also increased expenses in profit taxes from 446,330 Br to 13.35 million Br during the year, while wage expenses surged by 50pc to 187.42 million Br. Yet, reaching the loan cap limited its growth opportunities.

Amid these constraints, some banks have opted to focus intensely on loan collection, as conventional avenues for deploying their capital are blocked. According to Khadir Ahmed, founding president of Shabelle Bank, balancing growth and regulatory compliance remains ungraspable.

“We're exploring alternative revenue streams in the meantime,” said Khadir, one of the executives who signed the petition to the central bank, urging the regulators to reconsider their policies.

Regulators, however, maintain their position on the loan cap. According to Fikadu Degafe, vice governor, a study is underway to determine the potential impact of an exemption for new banks.

"The impact could be relative," said Fikadu.

Khadir is, however, eyeing short-term financing and potentially introducing fees for previously free services like transfers and withdrawals. However, Khadir acknowledges that "repayment for the short-term financing burdens the customers."

For Bedir Abdo, vice president of Rammis Bank, which began operations in June last year with substantial capital, Rammis has reached a bound, limited to mobilise deposits or disburse large loans fearing the impact in the coming years. It has scaled back its branch expansion plans like its peers, reducing the number from 40 to 15.

“The regulation is concerning,” he told Fortune.

Loan cap policies are not without historical precedent, though. Similar measures were adopted in the 1970s by countries including Japan, France, Italy, and Denmark to combat inflation. While the specific applications varied, the results were often mixed, with major repercussions including reduced competition in the banking industry, increased lending rates, and credit rationing. The broader implications of this policy are becoming evident as third-generation banks face these stringent regulations.

The pioneering interest-free finance institution, ZamZam Bank offers international banking services and derives a major portion of its revenue (40pc) from service-based income. Despite a strong initial capital base and a second-year recovery, Kadir Bedewi, its vice president, questioned the cap's effectiveness in abating inflation, particularly when considering the potential outflow of funds from established banks with large existing loan portfolios. Like others, ZamZam is tightening its belts in response to the cap.

"We've slowed down branch expansion to lower overhead costs," said Kadir.

It is an obvious cautious approach to capital expenditure. Kadir believes a system that better distributes the permissible loan volume could allow smaller banks to grow while still achieving inflation control objectives.

Some banks incurred losses for the first two years due to massive expansion. Ahadu Bank posted a 193.68 million Br loss for the year ended 2023, marked by high staff and operating expenses that soared due to the massive expansion. Tsehay Bank faced a similar fate with a 162.8 million Br loss.

Others had a bit of backstory. Tsedey Bank entered the commercial banking industry in September 2022, evolving from the Amhara Credit & Savings Institution. Upon transitioning, it bagged 30 billion Br in loans. However, its executives are among those who have opted out of joining the lobby group that dispatched the petition, although its executives say they were among the first to appeal to the central bank for a loan cap reconsideration three days after the directive was issued.

According to Mekonnen Yelewumwosen, president of Tsedey, micro and small loans are critical for stimulating production.

"We've shifted focus to micro and small loans," he said, "particularly for farmers seeking financing to boost productivity."

While third-generation banks struggle to stay afloat, industry observers saw the ripple effects extend to the share market.

Bereket Girma, operating in the Ethiopian Share Market, noted a troubling trend of declining share values and a reluctance to invest, a sentiment echoed by other industry observers. He observed shareholders voting to beef up paid-up capital, but hesitant to increase their shareholdings.

"It likely stems from anxieties about the overall economic climate," he said.

A 2021 directive requiring banks to increase their paid-up capital – existing banks to five billion Birr in five years and new entrants to seven billion Birr in seven years – raises concerns alongside the loan cap policy. As most new banks incur operational costs in the first years, they might find meeting the minimum capital requirement an uphill task, according to Eshetu Fantaye, a veteran banker. He fears their long-term sustainability under current regulations.

"Possibility of mergers or failure looms in the coming years," he said.

Nonetheless, the potential for consolidation through mergers or acquisitions with established banks raises concerns in the banking context. Eshetu argued that such a scenario would not work in the heterogeneous segments the third-generation banks are designed to cater to, affecting their market segment and customers.

"With some of them, it's like mixing oil and water," he told Fortune.

Eshetu criticised the aggressive branch expansion observed in some of the new entrants, which has resulted in high overhead costs and delayed their break-even point.

"Cost minimisation should be a key initial strategy," he said.

Financial analysts like Abdulmenan Mohammed (PhD) argue that the loan cup policy disproportionately affects new banks, which are not yet on equal footing with established institutions in terms of key performance metrics like loans, deposits, and capital.

“Who would invest in a bank that's haemorrhaging money?” Abdulmenan asked rhetorically.

He sees that these banks could alternatively invest their surplus liquidity in treasury bills, though this offers lower returns. He also warned of a domino effect; a struggling banking sector could lead to declining tax income from a weakened financial sector, economic stagnation impacting job opportunities, triggering business closures and a broader economic downturn.

"They should focus on digital than branch-based banking until the grip is loosened," he told Fortune.

The central bank has yet to address these concerns fully, leaving the third-generation banks in a precarious position. Experts continue to advocate for a more nuanced approach to loan growth regulation, hoping for regulations that reflect their newfound tools to fight inflation. Established businesses like the East Africa Plastic Centre continue to feel the squeeze, operating at reduced capacity due to the unavailability of working capital influenced by the banking industry's constraints.

PUBLISHED ON

Apr 13,2024 [ VOL

25 , NO

1250]

Radar | Oct 05,2024

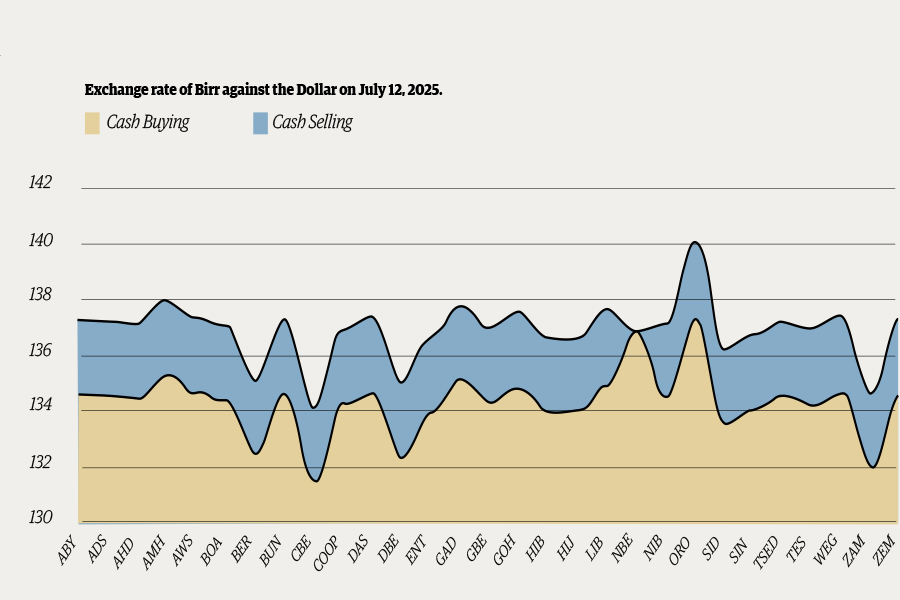

Money Market Watch | Jul 13,2025

Agenda | Nov 02,2025

Radar | Dec 04,2021

Fortune News | Dec 07,2019

Radar | Sep 03,2022

Fortune News | Aug 30,2025

Radar | Jul 23,2022

Fortune News | Jun 19,2021

Editorial | Oct 30,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Nov 1 , 2025

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) issued a statement two weeks ago that appeared to...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...