Jan 22 , 2022

By Elshadai Negash

With Ethiopia gearing up for the re-launch of its capital market in 2022, all eyes are on how one of Africa’s sleeping giants can create and sustain a market that can fuel the growth of its private sector. But without a concerted effort to address the waning information and education gap in its financial ecosystem and improve financial literacy for thousands, if not millions, of would-be investors, the effort could be a repeat of the exciting start, but stunted growth in similar African countries, explains Elshadai Negash (elshadai.negash@kemmcom.net), who leads Media Business, Communications, & Corporate Affairs at KEMMCOM Media & Communications.

Queuing for in-demand basic goods and services is not an unfamiliar occurrence in Ethiopian government offices as the public sector grapples with the need to speed up its flailing bureaucracy to meet the country’s sprawling urban growth. But on one afternoon in February 2021, the long lines at the Document Authentication & Registration Authority (DARA), Ethiopia’s notary outfit, told a different story.

The deadline for the authentication of documents to purchase shares of the country’s four new banks was only two days away. Men in their 30s and 40s attired in business casual and a few women sprinkled among the crowd, as if this was a diversity and inclusion photoshoot promoting the involvement of minorities, sat on the stairs and long chairs waiting patiently for their turn to present and authenticate their documents with the number-assigned notary officer.

Long breaths under their mask-covered faces, fiddling with their smartphone for the latest breaking news, and short detours to the nearby café for their afternoon caffeine boost told the story of a bunch who felt out of place. This was if they had not been offended by the country’s inability to fully digitalise these and other services while they, courtesy of a 250 dollar smartphone, can travel the world and back in 20 minutes.

On any given day, this is the sort of group wrestling against early morning traffic to travel from the outskirts of Addis Abeba to its centre spots to make it in time for their middle-class jobs or enjoying a meal with a friend or colleague at one of the city’s medium-range restaurants. The majority of the group were put off either by the substandard investor relations from the banks and deem the heritage association of the companies incompatible with their values. But the “few courageous” braved the arduous enlisting process after yielding to inflation or pressure from peer or heritage networks, but with very little informed advice on the operation of banks, their unique offerings or business models, or an independent assessment of their investment’s rate of return.

Welcome to Ethiopia’s new and growing investment community – the thousands, if not millions, of obscure faces who are neither canvassed by political parties to obtain buy-in for their economic policy nor given the appropriate information, tools, and advice to move their wealth wisely from their wallets and bank accounts.

It is the group of middle and high-income salary employees or middle-level business people who have escaped the poverty trap. They are looking at ways to protect their hard-earned income from inflation and turn their cash into investments. Literate enough to read and absorb quality information and too cautious in decision-making, their desire to hasten their ascent up the economic ladder is simply unmatched by the lack of quality information they require to make informed decisions.

The few “enlightened” ones resort to self-help and quick cash finance high-copy books sold on the streets and about a dozen bookshops in Addis. While providing a dose of knowledge dopamine, the reading only serves to confuse their decisions given these books are written for and are intended for people, market dynamics, and operating realities of environments vastly different to Ethiopia. They dig up newspapers, look for programmes on radio stations, and try their luck with business news on TV without a platform that either informs or builds their understanding of different investment options.

On the other side of town, the founder of an SME is standing in front of a conference room full of corporate executives to pitch investment plans for his five-year-old food processing company. Worn down by several attempts to secure loans from banks and in his third pitch in the last two months, he starts his presentation with a hint of nervousness.

The presentation goes well enough. He impresses his audience with his deep research and knowledge of his sector, its growth prospects, and the problems he is trying to solve. He is politely thanked and sent away by the group only to receive a rejection email a few days later. The investors say they were impressed by his presentation and recognised the potential of his business, but are not willing to put money into his venture. Informally, their colleague tells him over beer that his sector was not “sexy” enough for the investors.

The rejection echoes the coffee meeting he had with an official from a Development Financial Institution (DFI) a few weeks earlier. The official showed little interest in hearing his ideas because he was not a hot and trendy startup working in technology.

The reasons and justifications hurt deep because he has done his work. He prepared a proper investment prospectus, had his financials done independently by a certified consultant, and was working on a sector that deals with Ethiopia’s most fundamental problem of food security.

His investment requirement?

Fifty million Birr for a 10pc stake in his company – the same amount of money around sixty DARA queuers are willing to put down on buying of shares of a bank without reading its investment prospectus!

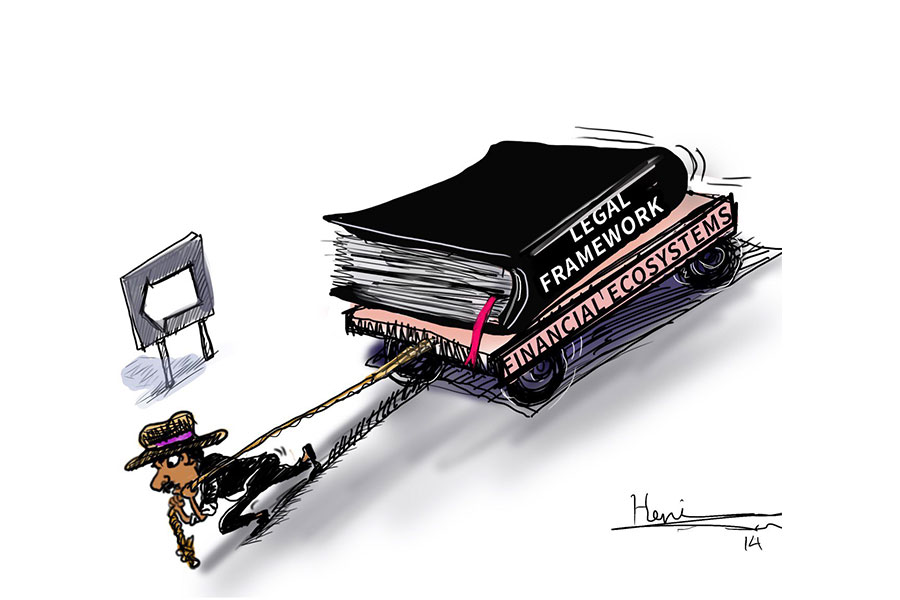

It is against the backdrop of such an investment disconnect that Ethiopia will launch its capital market this year. The Capital Market Proclamation, the important piece of legislation governing the market, was ratified by parliament last June. The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) has established a Capital Markets Project Implementation Team to steer the operationalisation of the Proclamation in a series of activities. These include the establishment of the Capital Markets Authority, the coordination work of setting up the Ethiopian Securities Exchange, and development of the required market infrastructure.

Like many African countries, the markets are scheduled for launch in 2022 with an initial group of companies, including well-established banks and insurance companies, urged on by the central bank's revamped minimum capital requirements, expected to list. They will be met by an enthusiastic group of hopefuls already doing informal trading by connecting on peer-to-peer networks like Telegram, which incentivises closed-group and similar-identity connections rather than open networks based on certified information and exchange of insights.

Where such a disconnect between people and information exists, the ideal way to connect people with information rests in a well-thought through communication strategy for all concerned institutions and a financial media ecosystem that delivers up-to-date, quality news, information, and insights to the investment community. The development of financial media should be given high priority in any financial or investor education effort as part of the development of the capital markets.

It will provide up-to-date news and information, advice from sector experts and improve the financial understanding of non-finance people. Financial media will have a big role to play in creating trust, delivering stories based on evidence, and developing a community of investors beyond Addis Abeba’s closed group of elites working in private equity, investment advisory firms, financial institutions, and the government.

The intervention, to borrow from international development speak, lies in two major frameworks.

The first would be “building the plane as you fly it.” It is to improve the corporate structure, audience development and management, business models, content strategy, and operational delivery of existing financial media to attain fit-for-the- purposes of the capital market. These interventions, breaking away from piecemeal media development solutions of journalist training, fact-finding missions, and fact-checking capacity building training, will prove more sustainable in building at least five or six competitive media outlets scaling up efforts to serve the growing investment community.

The second would focus on ecosystem building beyond restructuring traditional media outlets. This would involve encouraging sector-specialist, mobile-first, and dedicated information portals to mushroom in a startup sandbox before market testing. Experimental areas include highly-informal and volatile sectors like real estate and construction, but must also involve efforts to deliver financial education and inclusion to underserved segments of society.

While borrowing heavily from practices of advanced markets, any effort of improving Ethiopia’s financial ecosystem must recognise and augment the work of well-functioning domestic markets for widespread adoption. It must also emphasise the addition of local content, produced and distributed in local languages, and contributing to bigger societal goals of shared prosperity and wealth distribution among the merited.

Promoters need not look too far for inspiration on how to build this ecosystem. Nestled in Addis Abeba’s urban jungle of warehouses, trading shops, distribution centres, and upcoming shopping malls, Mercato’s well-oiled business practices serve as an important lesson in effective utilisation of space and time, building of trust between market actors, and the informal building of an investment class through traditional saving and investing mechanisms like equb. Without the support of financial media, this market developed its own structured information-sharing mechanisms that boosted the confidence of market participants.

At a basic level, they provided solutions to growing businesses struggling with cash flow, credit trustworthiness, and inventory issues where banks failed to absorb the risk. As they scaled and built their networks, they laid the foundation for some of Ethiopia’s leading financial institutions by turning this social capital into monetary capital.

The plush headquarters of some of the country’s leading banks today are testaments to the dedication of equb members who two or three decades ago pulled resources together to form some of the first private banks and insurance companies in Ethiopia. These heroes, now in their 60s and 70s, can enjoy the fruits of their investment in their retirement with a mix of contentment and regret.

The contentment comes from their ability, when very few others saw it, to see a future of big banks in Ethiopia. The regret comes from Arat Kilo (a moniker for the Prime Minister’s Office) and Behrawi (a moniker for the politically-influenced National Bank of Ethiopia) threatening to extinguish this vision through a series of paranoid steps including the block of the launch of a stock market in 2001.

Both Arat Kilo and Behrawi, urged on by financing from multilateral institutions and a mindset change that now looks to be giving the private sector some breathing space, have laid the groundwork for a capital market this time. The danger is creating a market that is disconnected from the realities of thriving markets across the country. Building the country’s financial media ecosystem in the right way is an opportunity to do it right this time.

PUBLISHED ON

Jan 22,2022 [ VOL

22 , NO

1134]

Commentaries | Jan 18,2019

Editorial | Aug 27,2022

Fortune News | Mar 16,2024

Featured | Jan 05,2019

Fortune News | Jul 13,2024

My Opinion | 132151 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 128561 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 126482 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 124091 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 12 , 2025

Political leaders and their policy advisors often promise great leaps forward, yet th...

Jul 5 , 2025

Six years ago, Ethiopia was the darling of international liberal commentators. A year...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The Addis Abeba City Revenue Bureau has introduced a new directive set to reshape how...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Addis Abeba has approved a record 350 billion Br budget for the 2025/26 fiscal year,...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By RUTH BERHANU

The Addis Abeba Revenue Bureau has scrapped a value-added tax (VAT) on unprocessed ve...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Federal lawmakers have finally brought closure to a protracted and contentious tax de...