Radar | May 08,2021

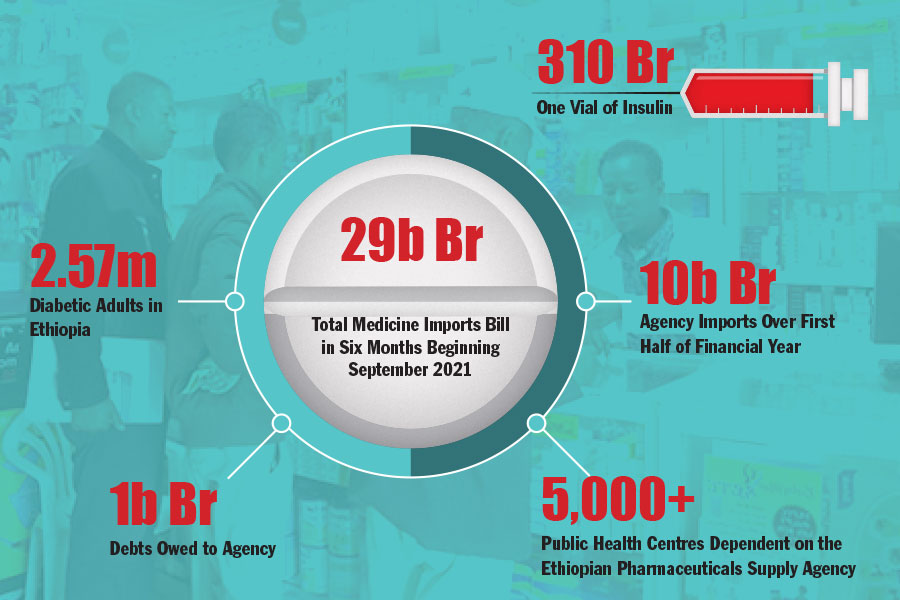

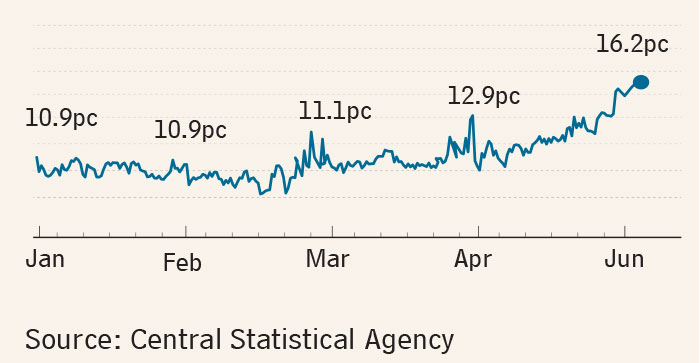

Consumers in Ethiopia wake up each day to find the cost of living edging ever higher. The outcome is muffled consumption on most goods, except those essential and, evidently, items of life and death. The latter category is medicine. The private health sector has long been outside the affordability of the majority of citizens. Lately, not even public institutions with fat budgets can offer shelter. From prescription medications to personal protective gear, even referral hospitals like Tikur Anbessa (Black Lion) have become less affordable alternatives. Patients are demanded to cover the cost of surgical gloves for use by health professionals for checkups. A single vial of insulin is sold for 310 Br, double what it used to cost a year ago.

Driving prices up is the sharp depreciation of the Birr against major foreign currencies, which has made imports expensive. But it is only one of many reasons. Another is the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which exerts upward price pressure in the global health industry as demand remains high. Supply chain disruptions have not done anyone a favour either, with shipping costs quadrupling over the past two years. The fuel on the fire is a severe foreign currency crunch in the economy, which debilitates the capacity of pharmaceutical importers to source much-needed medications - pharmaceutical products are not only expensive but rare to come by. Even local manufacturers such as the state-owned Ethiopian Pharmaceuticals Manufacturing have their hands tied, cutting back on production for lack of inputs.

Taking the pain for the convergence of global and local disruptions that have escalated prices in the health sector are some of the most vulnerable groups in society, those whose health is compromised. As many are hoping for relief from the affront of inflation, in the case of patients, the ache from the rise of the cost of living is becoming all too literal.

PUBLISHED ON

Mar 30,2022 [ VOL

22 , NO

1144]

Radar | May 08,2021

My Opinion | May 23,2021

Fortune News | Jun 23,2019

Commentaries | Dec 04,2021

Viewpoints | May 23,2021

Radar | May 23,2021

Films Review | Jul 13,2019

Covid-19 | Jun 11,2021

Fortune News | Oct 23,2021

Fortune News | May 07,2022

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...