Viewpoints | Jan 07,2023

Dec 19 , 2018.

The Main Department for Immigration & Nationality Affairs Office has been on a roll lately. In a set of reforms it introduced this year, it lifted the excessive fines levied in foreign currency against Ethiopian-born foreign nationals who overstay their visits to Ethiopia.

The authorities also attempted to improve and broaden services by partnering with Commercial Bank of Ethiopia to facilitate fee payments for passport issuance and moved two departments to another location to reduce congestion at the original location. They also contracted out the delivery of passports to the Ethiopian Postal Service, redirecting the long and snaking lines of people that used to jam its gates.

The scene at the Department, located off Churchill Road, has been different for the past few weeks, however. The addition of new requirements for passport renewals and new ones have meant inconveniences to citizens that include arbitrary rejections of those that came prepared.

This is a step backward for the office. The office justifies its actions by claiming that it needs to curb illegal migration and address foreign currency shortage issues it faces in printing passports.

Such reasoning is emblematic of the Ethiopian public sector that usually provides lackluster services. If there are problems and obstacles that need to be addressed in providing the necessary services, they are more often than not accomplished at the expense of members of the public. The responses are devoid of considerations of the public interest and lack creativity and the application of constructive solutions.

The public sector in Ethiopia is regarded as inadequate and incompetent, where close to 70pc of its workforce is described as support staff. Paid far less than their counterparts in the private sector and non-governmental organizations, many of the 1.5 million civil servants are demoralised and unmotivated.

Civil service is considered an entitlement provided by the state to grateful citizens. Its poor performance and incompetence, which would be unacceptable in the private sector, is tolerated, because it stands for a higher cause. It is what Jacob Weisberg, an American political journalist, described as paternalistic activism within government, a method that most lends itself to an impoverished public sector.

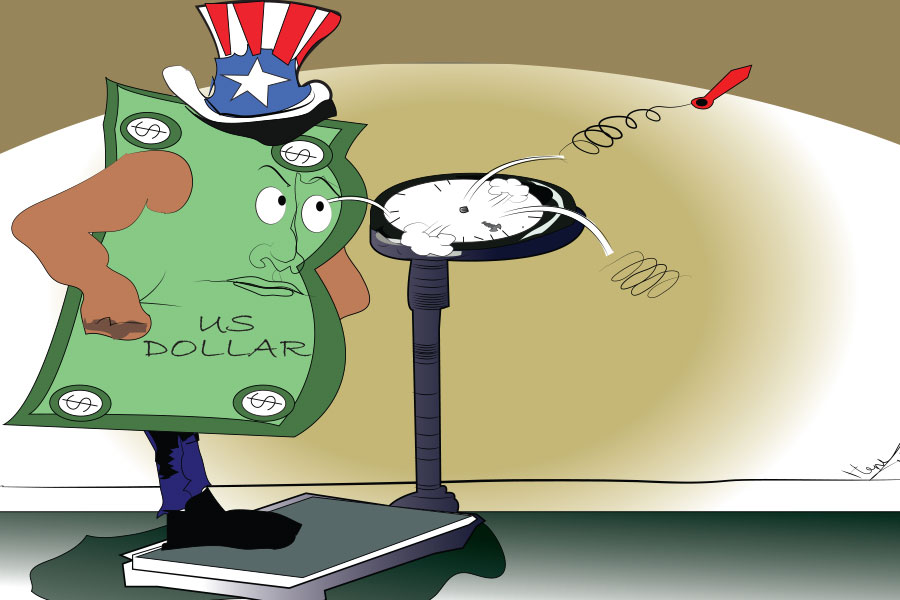

Public services are rarely evaluated for their monetary values. Although taxpayers must honour their duty, they are entitled to the bare minimum of inconveniences and delays. And given the current economic undercurrents, the costs to an unreformed public sector could be high.

There are indications that the coming few years will have two constants: a growing involvement of the private sector in the economy and declining spending by the public sector.

The completion of long-awaited infrastructure projects, including six industrial parks coming online in just three months through December, should be able to attract foreign investment, especially if political tensions are reduced.

But the importance of infrastructure has for long been muffled by a lack of regulatory capacity by state and monetary policies that have dissuaded the domestic private sector from taking advantage of this potential.

This could change given planned privatisations in the telecom, logistics and financial sector; slightly more flexible policies by the central bank toward foreign exchange; and better performances in non-export sources of foreign currency revenues such as remittances. These could benefit private businesses that have been starved for hard currency and credit, as well as offering breathing room in the regulatory regimes.

These developments are in addition to the contractionary fiscal policy the government has taken this past fiscal year to help reduce macroeconomic imbalances such as inflation that averaged 13pc last year, a 12.4-billion-dollar trade deficit and current external debt that is almost a third of gross domestic product. Government spending is most likely to scale down further, given current policy directions the incumbent is planning to take.

But all of these could be complicated if the public sector continues to be inefficient, a matter that cannot be dispelled through the mere introduction of policies. For the private sector to grow, and the economy to be efficient, there needs to be a professionally competent and non-partisan public sector, able to facilitate good governance - instead of merely policing markets, or rather obstructing their functions.

Businesses can hardly create jobs, supplement import substitution, supplant domestic revenues and become globally competitive if the public sector fails to create an environment for the efficient allocation of resources and ensure the unhindered movement of capital, goods, services, people and - yes - information.

Just as important, since the government needs to reduce spending, the public sector must become efficient enough to provide adequate services with limited resources. The public sector, instead of supporting a well-compensated, motivated and competent workforce, makes do with poorly paid, inept and unmotivated employees. Capitalizing on the civil service should be considered an investment as good and as necessary an outlay as spending on public infrastructure projects.

This could help the bureaucracy to see the public sector not as a provider of favours to the public, but as an entity that offers services in return for what taxpayers pay into the coffers of the government. The concept of value for money should hold sway.

Similarly, instituting performance measurements used in the private sector could also be used for the public sector to improve services. Performance evaluation tools that use inputs from users of the services, the accountable body and from private firms that work with public agencies can be implemented. The performance evaluation, if planned and overseen by an independent body, could provide accountability and will indicate where improvements are needed.

Politics may, of course, stand in the way. Performance information may receive scant attention from political bosses much the same way audit gaps in federal agencies have been treated in the past.

Indeed, there has never been a shortage of programmes that measure performance in the public sector, including Business Process Re-engineering, Kaizen, Balanced Scorecards and Deliverology, just to mention a few. Despite the time and effort it takes to implement these programmes, they have brought little improvements in service provisions to the public sector.

In Ethiopia, this may be because standing committees have been unable to scrutinise performance and forward their recommendations, while parliament has neglected to press the executive branch during the passing of budget bills.

Collecting proper data, and even bringing it to light alone, would change little to alter the public sector’s sense of entitlement. Parliament should be willing to sanction incompetence by either insisting on an incentivising allocation of budgets or change the inadequate leadership now presiding over government agencies.

PUBLISHED ON

Dec 19,2018 [ VOL

19 , NO

973]

Viewpoints | Jan 07,2023

Fortune News | Jul 08,2023

Editorial | Feb 16,2019

Radar | Oct 20,2024

Commentaries | Sep 17,2022

Commentaries | Jul 17,2022

Fortune News | May 20,2023

Fortune News | Mar 16,2020

Viewpoints | Mar 12,2022

Viewpoints | Dec 17,2022

Photo Gallery | 175340 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 165565 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 155891 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 136808 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

In a sweeping reform that upends nearly a decade of uniform health insurance contribu...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

A bill that could transform the nutritional state sits in a limbo, even as the countr...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A long-planned directive to curb carbon emissions from fossil-fuel-powered vehicles h...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Transaction advisors working with companies that hold over a quarter of a billion Bir...