News Analysis | Jan 05,2020

Aug 1 , 2020.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) had an audience with leaders of the opposition bloc - if there is one to be described as such - in the middle of last week. Straight away, the weight of things was self-evident in the facial expression of the politicians. They were on the receiving end of Abiy’s retort to their dose of remarks. Ironically, for a country that underwent a harrowing month - of violence, internet blackout and an acute rise in societal polarisation - its Prime Minister looked rather relaxed.

Abiy had shed the stern and dour-looking persona he had donned when he appeared in military fatigues before mainly security officials in the week following the death of Hachalu Hundessa, an iconic musician and political activist. It was as if he was speaking now to a different audience, not just in the hall, but nationally as well.

His message?

Law and order shall be restored. Too late to come to this circle though. The loss, the pain and suffering many were made to endure were not only too much to carry. They were all needless and could have been avoided. He pledged national elections will be held at most 10 months from now. He appears determined to continue unabated with the Prosperity Party’s reform agenda, despite the remonstrations of those that were said to be obstacles.

It was a fruitful discussion in as much as there was a positive feedback loop between the opposition political figures and the Prime Minister. The former expressed the importance of the measures the government was taking to restore law and order, and the latter agreed. Notable about the discussion was the suggestion for a dialogue to arrive at a national consensus - an appreciable initiative that had been called for as law and order became elusive over the past three years. If indeed such a dialogue can be inclusive of the plural voices on the ground, it would signal hope for a political settlement that heralds multiparty democracy.

Alas! The fierce critics of the administration are now thrown in jail, fighting allegations the media - both public and private - are more than happy to apportion guilt ahead of the courts. The conversation last week was held with those who are evidently subdued, hence docile. See no further than the bizarre rhetoric some of the leaders have had, all meant to appease and please power.

The chance for a meaningful grand political bargain seem to have slipped through the fingers. The language and mode of engagement between the incumbent and the opposition, at the outset amicable, slowly turned into active confrontation and in some cases even violent exchanges. But if there were occurrences here and there that served as indications of the thinning of the political space, political developments after the death of Hachalu seem to have been the nail in the coffin.

What occurred over the past month was the solidification of ideology and worldview between what are becoming two major political groups. Between them, they are leaving no room for compromise, dialogue or reflection. They are diametrically opposed to each other, and their engagement has been to wipe out or beat the other into submission, not find common ground.

The "unionist" and the "multi-culturalist" forces, two of many terms and expressions used to describe them, did not emerge recently. They have existed ever since the beginning of Ethiopia’s modern state as far back as its foundations in the late 19th century. But its glaring manifestation of a deeper cleavage become apparent in the late 1960s when leftist ideologies pervaded the national discourse. These differences have simmered and boiled over from time to time, while each movement underwent major revisions as the socio-cultural and economic circumstances changed and they had to appeal to new generations.

Despite the exclusive undercurrents both political views held toward each other, there seemed to be over the past two years an attempt to mute their differences. Various factors may have worked to this end. It may have been a carryover from the loose alliances in the fight against what was perceived to be a common enemy - the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) – and an underestimation of the acute differences in each other's outlook.

It may also have been a result of the rise to power of Prime Minister Abiy, who through circumstances of ascension, the way he carried himself, and his early style of exercising of power appeared to transcend both movements. Instrumental to this was his Medemer, loosely translated to “positive-sum,” conception. It was an umbrella both movements swiftly cocooned under.

Although either side paid lip service to the possibility of co-existence, all that is obvious now was that the brief interlude of amiability was not sincere, and both had severely misunderstood the motives of the other. This was unhelped by the lack of effort on the government’s side to engage them in a much needed political settlement - grand bargain - where they could find common ground. Even if it had not been achieved, it would have served as a measure of the wide gap or possible points of overlap that had been obscured and disfigured by rhetoric and hyperbole.

The possibilities of this are now highly unlikely. The language has perceptibly changed. Either group now sees the other as an enemy to be vanquished, not as a legitimate contender for political power. It is no longer politics, where the right of the other to exist is avowed. It is war, where the opposing group is portrayed as an existential threat.

This is not helped by either group’s refusal to self-criticise or to see the error in their ways - of which both have - or to acknowledge the opposing group's legitimate political calls and causes - of which both have as well. It is evident now that both movements have strayed away from each other, almost beyond mending. Neither is willing to act or behave in good faith.

The far more destructive consequence of this has been the hallowing out of centrist voices from the political spectrum. Given the stupefying level of bias and disparagement being thrown around within the political space, the appetite for moderates to engage is obviously meagre. Even if the possibility of liberal democracy may be out of reach, returning moderation and plurality to the electoral discourse is of paramount importance. This is to avoid two possibilities in Ethiopia’s future. One is where the government is unable to ensure law and order, leading to a violent split-up of the federation.

The other is the creeping arrival of authoritarianism, Ethiopia’s default state following every serious contention for political power.

These extreme possibilities can only be avoided through the aid of centrist voices, not the militant movements that are currently crowding the political space. The seeds for this exist within each movement. The evidence of this can be witnessed in the worthwhile efforts within the past two years to reach across the aisle, but they were greatly glossed over and forgotten as the radical elements of both groups gained more prominence.

Moderation, nonetheless, can only rise within a political space where opposing groups can freely engage. This requires an inclusive national dialogue and accountable institutions free from the personalisation of power. Most critically, a fair playing field that gives each side an equal chance at winning is necessary.

Without these requirements in place, the playing field will be laid bare for radical and militant elements willing to engage outside the constitutional and institutional orders. Only the government is capable, and in charge, of preparing and maintaining this playing field. The onus, as in most times, falls on its shoulders.

PUBLISHED ON

Aug 01,2020 [ VOL

21 , NO

1057]

News Analysis | Jan 05,2020

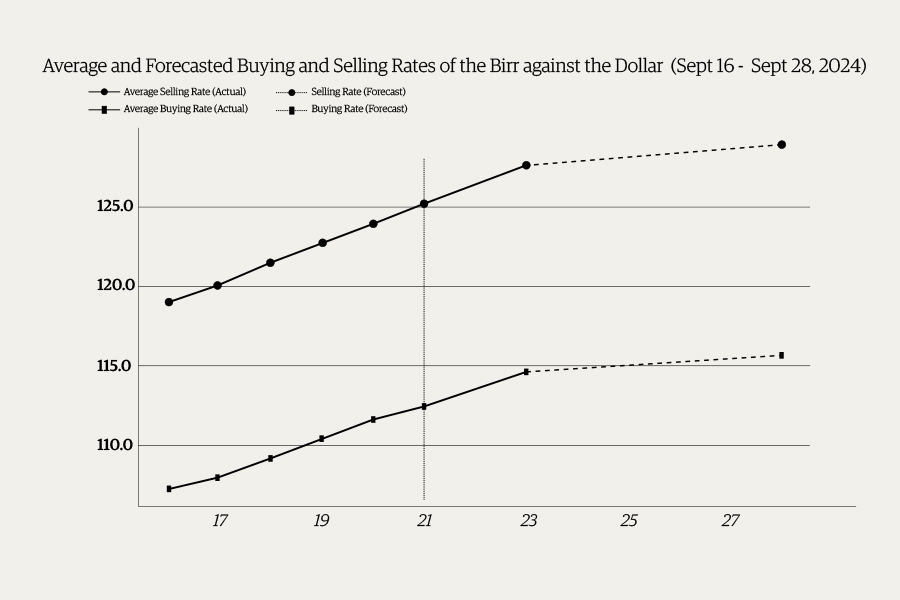

Money Market Watch | Sep 22,2024

Featured | Sep 27,2025

Sunday with Eden | Apr 02,2022

Commentaries | Jun 10,2023

Commentaries | Jun 22,2024

Fineline | Nov 02,2019

Viewpoints | Mar 16,2024

Radar | Sep 23,2023

Commentaries | Jul 13,2020

Photo Gallery | 180592 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 170787 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 161869 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 137296 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Nov 2 , 2025

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) has scrapped the credit-growth ceiling that had s...

Nov 2 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

The burgeoning data mining industry is struggling with mounting concerns following th...

Nov 2 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

Berhan Bank has chosen a different route in its pursuit of a new headquarters, opting for a transitional building instea...

Nov 2 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Nib International Bank S.C. has found itself at the epicentre of a severe governance...