Jan 11 , 2020.

If there is anything about the current development in the political arena, it is not dull. Political forces are evolving so fast and so much, formations and re-formations of alliances are keeping pundits on their toes.

The newly christened ruling party, the Prosperity Party (PP), had its first executive committee meeting two weeks ago. The only party that did not join Abiy Ahmed’s club, the TPLF, likewise convened its congress, stamping on the long-anticipated divorce with the three parties in the defunct EPRDF that have merged into the Prosperity Party. It came as no surprise when it became an opposition party for the first time since 1991.

The decision by the Prosperity Party and the TPLF to go their separate ways marks a horizontal break-up within the incumbent party. No doubt its consequences will be felt dearly, particularly as they will have to divide among themselves the various government cadres strewn across the federal government and within the Addis Abeba City Administration. The Ethiopian bureaucracy will eventually become a battleground for political manoeuvring.

De facto one-party rule had persisted in Ethiopia for over almost three decades under the EPRDFites, causing the state and party to become intertwined. The break-up of the latter is likely to have a similar impact on the former.

It might have been Max Weber, the German sociologist, who popularised the term "bureaucracy" and provided it with a formal description that has been referred to ever since the early 20th century. But it was John Stuart Mill, a political economist and a civil servant himself, who formulated the essential characteristics of monarchies, such as that of early Russia and China: the ubiquity of the bureaucracy.

Although Mill did not know it at the time when he published, in 1861, an essay titled, "Considerations on Representative Government", where he makes his case, he could as well be talking about Ethiopia under Emperor Haile Selassie. The Emperor played the lion's share in modernising Ethiopia`s bureaucracy but ensured that its entire loyalty was to the monarchy. In the words of Seyoum Haregot, a state minister then and wedded to the Emperor`s granddaughter, what Hailesellasie had built was a bureaucratic empire.

An author of a book bearing the same phrase, Seyoum was one of the many senior officials serving the bureaucratic empire incarcerated by the junior military officers who had toppled the Emperor. The military junta, the Dergue, took the reins of power only to face machinery that would distinctly fail to conform to Marxist-Leninist ideals.

Mengistu Hailemariam (Col.) and company had to go back to the drawing board. They had attempted to reshape the bureaucracy in their thoughts with the principal purpose of establishing a socialist state. That project was abandoned later on, first as the Soviet Union ceased to fund socialist aspirations around the world, including in Ethiopia, and then when the Derguefaced defeat by rebels from the north but with as much leftist roots.

For the ruling coalition, the EPRDF, that subsequently took power, the bureaucracy was promised to be nothing but a professional body free of political interference. That was at least the suggestion from a Constitution that is at least two-thirds liberal in its content and steadfast in its commitment to checks and balances on state power.

The EPRDF, in the end, failed to walk the talk. During five consecutive general elections, it arguably won very comfortable majorities in federal, regional and local government legislative bodies. It used - or rather abused - state power to radicalise a new generation of civil servants with its own brand of federalism and developmentalism through endless indoctrination. It only promoted bureaucrats who toed the party line. What was left was a bureaucracy without its own identity, deeply unprofessional, highly politicised and no less insecure.

National elections are slated to take place this year, while there is already a bitter contestation to control the political narrative, before the bureaucracy is not insulated from its ills. The scenario will be a fractured government unable to carry out its duties, including the protection of civil liberties and the provision of public goods and services.

This is a result of the unravelling of the ruling coalition, undergoing ever since 2018. It might not have been as formal as a divorce; but the dysfunctional hierarchical relationship inherent within the EPRDF has been evident for at least two years.

The climax has been the formation of the Prosperity Party, Abiy's "integrationist federalist" answer to rebalancing the "multicultural federalism" of political forces reemerging under the recently formed Coalition for Democratic Federalism (CDF).

An unprecedented and sudden breakdown in law and order, in stark contrast to the relative political stability in Ethiopia since the ousting of the Dergue, has revealed the weak handle the top leadership of the ruling party has come to exert on that of the lower one. It has signified a vertical fracture within the party.

In as far as the EPRDF and its allies controlled every seat in federal and regional parliaments and city councils, the vertical and horizontal fracture of the party leaves a government that is nothing but divided. It is uncharted territory for Ethiopia.

Theoretically, it should not be a bad thing. The scenario is only natural, considering the multiparty democratic spirit of the current Constitution. It allows for a government with a diverse parliament as well as a federal system where regional, federal and local administrations could be filled with ideologically diverging and competing multiple political parties.

What the Constitution does not envision is the politicisation of the bureaucracy along these lines. It is supposed to be the preserve of strictly administrative functions. It should be as rule-based, rigidly rational and soulless as Weber described it.

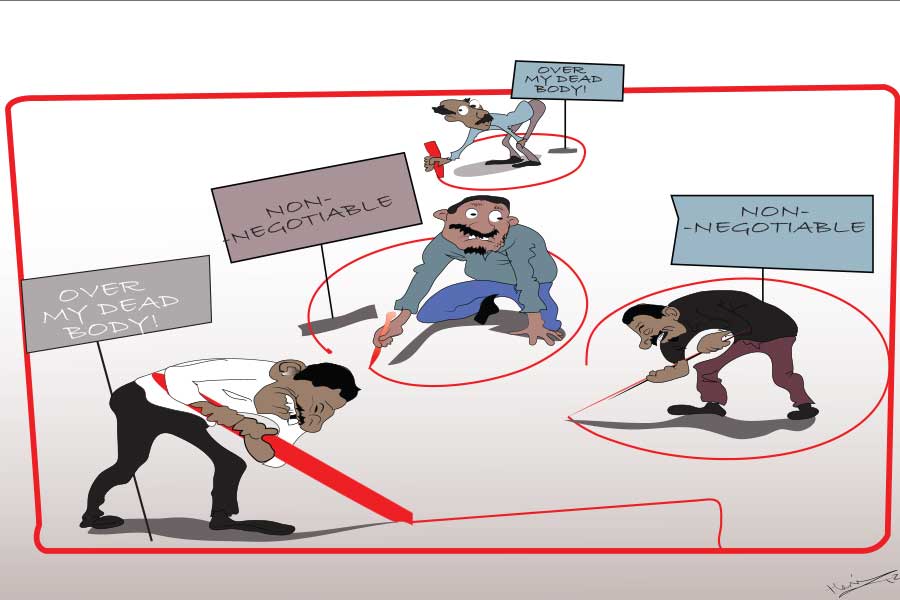

But Ethiopia’s bureaucracy has never been defined in this manner. Thus, its historical politicisation and the lack of identity it has been denied as a result of the autocratic inclinations of successive regimes means that its loyalty is bound to be seen as a winnable asset among the political contestants.

The attempt, if any, to insulate the bureaucracy from political power contestation will not be easy. Unlike political appointees to democratic institutions, top bureaucrats are required to work hand-in-glove with ministers to execute public policy. There cannot be a clear line or rule for every interaction that takes place.

Some steps can be taken to mitigate this problem. The Federal Administrative Procedure that is on the legislative track at the parliament is a good place to start. In forcing a thorough system of judicial review to ensure administrative transparency and accountability, it can help to impose discipline on civil servants unable to maintain not only professionalism but also exhibit partiality. It would go a great length in curbing improper political interference in the administrative decision-making process.

It would also be helpful to consider formal whistle-blower protection laws to empower individual civil servants against elected public officials who are not willing to play by the rules.

None of these rules and regulations will, unfortunately, matter if the political will does not exist. Political players, especially the incumbent, have to fight the temptation to use the bureaucracy in their contestation for power.

It is one thing for a class of unelected officials to lose their neutrality and serve one master. It is quite another for a body of government that should be working like a well-oiled machine to be pulled in divergent directions. The result will be a complete breakdown of the Ethiopian state.

PUBLISHED ON

Jan 11,2020 [ VOL

20 , NO

1028]

Viewpoints | Aug 20,2022

Fortune News | Dec 05,2018

Viewpoints | Apr 15,2023

Editorial | Jan 04,2020

Fineline | May 02,2020

Editorial | Oct 11,2025

My Opinion | Dec 19,2020

Viewpoints | Dec 29,2018

Viewpoints | Jun 25,2022

Viewpoints | Jul 18,2021

Photo Gallery | 174446 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 164670 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 154845 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 136672 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 12 , 2025

Tomato prices in Addis Abeba have surged to unprecedented levels, with retail stands charging between 85 Br and 140 Br a kilo, nearly triple...

Oct 12 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

A sweeping change in the vehicle licensing system has tilted the scales in favour of electric vehicle (EV...

A simmering dispute between the legal profession and the federal government is nearing a breaking point,...

Oct 12 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A violent storm that ripped through the flower belt of Bishoftu (Debreziet), 45Km east of the capital, in...