View From Arada | Jul 24,2021

Jun 19 , 2021

By Brook Kebede

Gender stereotypes and social, religious and cultural factors can make it very difficult for women to enter into politics and compete on a level playing field. Under these circumstances, laws only serve to nudge in the right direction, and this they could do harder, writes Brook Kebede (brook.kebede@uog.edu.et), lecturer of law at the University of Gonder.

In Ethiopia, women's main responsibilities are considered to be taking care of the family and the home. As a result, the underrepresentation of women in the social and economic spheres has been rife, not to mention contributing to a terrible record of violence and human rights abuses. Besides, a patriarchal system has created obstacles in women’s political participation.

Laws speak differently. Ethiopia’s Constitution provides a guarantee for gender equality and prohibits any discrimination on the grounds of sex. Besides, gender mainstreaming is included in several national policies that pinpoint the main factors for women political participation. There is certain progress as a result. In the past five general elections, the share of women in parliament has grown from two percent to over a third in the last one. But the progress is uneven and slow.

The administration of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) appointed women to more than half of the ministerial positions. It also nominated the first female Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and the second woman head of state. Birtukan Mideksa also chairs the National Election Board of Ethiopia (NEBE), which has been in the spotlight over the past few years.

The active, equal and full engagement of women and men in every political and decision-making process as voters, candidates, elected officials and electoral management body staff is significant. In this respect, international human rights documents that lay the legal foundations to make this a reality, the increasing prioritisation given to women’s empowerment by governments, the international community, civil societies and businesses and an increasingly strong women’s movement are producing positive developments.

It is important to note here that gender mainstreaming in law-making has been critical here. The election laws enacted by parliament and subordinate directives issued by the Electoral Board do not explicitly recognise gender-based quota or any other measures that seek to achieve fair gender representation. However, the Constitution provides that state and public institutions ensure gender equality.

Thus, when conducting an election for leadership positions, any political party is required to ensure equal representation. Similarly, the recruitment of founding members of a political party needs to reflect such considerations and the contribution of members of the local community, and elections for a party leadership shall account for gender representation. When the party fails to do so, the directive states that it is mandatory to provide evidence for the political party's efforts in this regard.

There are no sanctions applied to political parties who nominate no or very few women to election staff positions. Consequently, while the situation is gradually improving, the proportion of election staff who were women during the fifth elections was minimal. And although representation is considered necessary in determining the financial support that the government provides to a party, the law fails to provide additional support measures to ensure the right of women to participate in political parties and run for office. There should have been mandatory requirements for political parties to have female candidates and leaders in this respect.

Voter registration also establishes a record of the voter eligibility of citizens and is aimed at ensuring that all citizens, male and female, can exercise their democratic right to vote. Here, it is mentioned that one of the particulars that need to be included in the electoral roll is gender. Protection is provided for certain groups of the community, including pregnant women, to be given priority during registration and voting.

Most of the directives issued by the NEBE are providing responses for gender inclusiveness. For instance, an organisation or institution licensed to provide voter education shall emphasise that women have the same constitutional rights as men to elect, be elected, and exercise other democratic rights. Besides, any teaching methods, languages, documents, and materials used by the organisation or its instructors or trainers need to promote women's equality. The Electoral Board also proactively takes gender into account in the analysis, planning and implementation of all its activities and interactions with other stakeholders involved in electoral processes.

The reality is much less rosy than what is written on paper. Women face disproportionate obstacles and discrimination compared to men. This is because gender stereotypes and social, religious and cultural factors can make it very difficult for women to enter into politics and compete on a level playing field. Women often have greater family commitments, making it difficult for them to travel and spend time away from home. In emerging democracies, women are often less educated than men, less connected and have less access to information.

It is not lost anyone that cultures and traditions have created a political system too lopsided for women to participate. The law could go one more step and explicitly recognise the quota system for women to be candidates and leaders of political parties for women's effective and equal participation in politics and elections.

Although the new electoral laws include provisions to ensure gender equality in political participation, the lack of additional support, such as the quota system, is a significant gap to address the discrimination against women in the political arena. There is no denying that awareness and poverty serve a great deal to hold back women in Ethiopia and that laws could only go so far. But the right type of nudge could go a long way to force the agenda front and centre.

PUBLISHED ON

Jun 19,2021 [ VOL

22 , NO

1103]

View From Arada | Jul 24,2021

Verbatim | Mar 16,2019

Fineline | May 02,2020

Viewpoints | Jun 26,2021

Editorial | Nov 13,2021

News Analysis | Jan 05,2020

Editorial | Apr 03,2021

Viewpoints | Mar 09,2024

View From Arada | Dec 29,2018

My Opinion | 131507 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 127863 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 125841 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123471 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

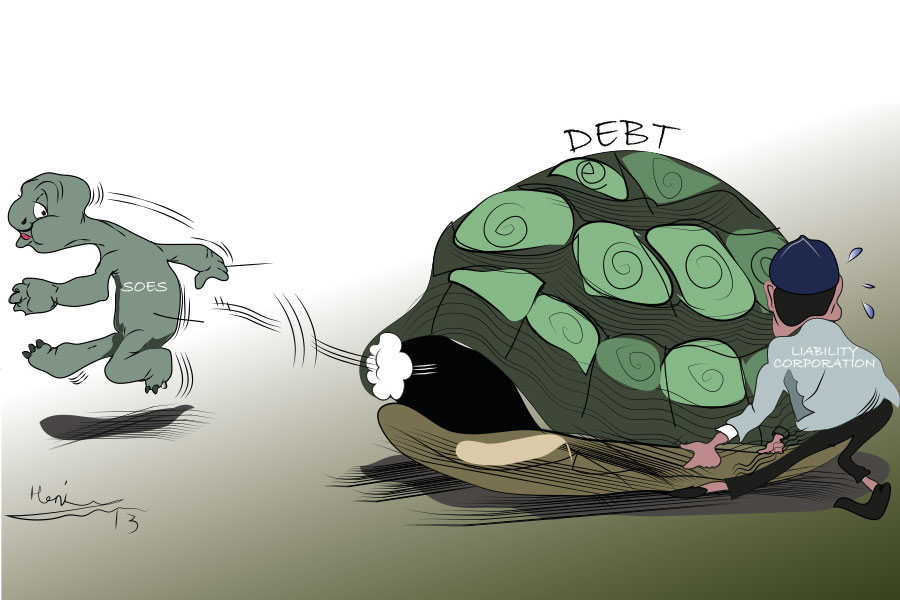

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jun 14 , 2025

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars...

Jun 7 , 2025

Few promises shine brighter in Addis Abeba than the pledge of a roof for every family...

Jun 29 , 2025

Addis Abeba's first rains have coincided with a sweeping rise in private school tuition, prompting the city's education...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Central Bank Governor Mamo Mihretu claimed a bold reconfiguration of monetary policy...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal government is betting on a sweeping overhaul of the driver licensing regi...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Gadaa Bank has listed 1.2 million shares on the Ethiopian Securities Exchange (ESX),...