Dec 25 , 2018

By Zinabu Samaro (PhD)

There seems to be a consensus that foreign direct investment positively affects developing economies. But when it comes to non-tradable sectors, it would instead exacerbate the foreign currency shortage, writes Zinabu Samaro (zinabu.samaro@gmail.com).

The Ethiopian government has been trying hard to attract foreign direct investment (FDI). However, the emphasis has been on export sectors.

The government had been resistant to liberalise “strategic sectors” such as banking, insurance, telecoms and other non-export sectors. However, in recent months, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s (PhD) administration has publicly announced that the government would be selling stakes in companies such as Ethio telecom.

This reversal of long-held policy has been praised by the international community, media and commentators. Some multinational telecom companies appear very excited to enter into the lucrative market. Finance has also been one of the areas where developed and middle-income countries have been pushing the Ethiopian government to liberalise. However, the announced move aroused heated debate among Ethiopians on its merits and demerits.

While several issues have been raised, there are few commentaries and debates regarding the implication of selling stakes or inviting in new foreign investment into the telecoms, banking and other non-tradable sectors on the balance of payments of the country. But it is important to note that there will be grave implications that arise from a large inflow of FDI into sectors that do not export a significant proportion of their products or services on the already precarious balance of payments (BOP).

Ethiopia’s persistent trade deficit has been the main culprit for persistent hard currency shortages. The nation’s external trade has been in deficit for close to a century. The only exceptions were two years in the early 1970s when a combination of unusually large receipts from sales of oilseeds and pulses resulted in a small surplus.

The trade deficits have been persistently widening since the modest opening up of the economy in the early 1990s when the growth of imports began to far outpace the growth of exports. Exports, which used to cover over four-fifths of imports in the 1980s, covered just about 20pc in the past few years.

Moreover, Ethiopia’s trade deficits are fundamentally structural in nature: they are features of the low-skill, backwards-technology-based economy rather than transitory phenomena. The main cause is that the country exports low-value-added commodities while importing more skilled and technology-intensive products. As a result, the export promotion drive of the government and its international partners has utterly failed to reverse this trend.

Therefore, the only way to sustainably address the trade deficit is by changing the overall structure of the economy, improving the technological structure and composition of exports, and reducing over-dependence of the nascent economy on imports. The only sustainable solution is to realise a structural transformation of the economy.

Notably, no amount of FDI could solve this problem unless the underlying structural problem is solved; and in fact, FDI into non-tradable sectors is likely to worsen it.

In recent decades, globally, there has been a strongly positive opinion about the development impacts of FDI into less developed economies. However, the near-consensus on the overall positive role of FDI in developing countries ignores some important insights from the non-mainstream schools of economic thought. This includes Ethiopia’s own early 20th-century intellectual Gebrehiwot Baykedagn who considered FDI to be equivalent to prohibitively expensive loans.

This is because, by definition, foreign investors bring capital into a less developed economy to make profits - over and above the amount they brought in - which they will eventually repatriate to their home countries. Put differently, by definition, a successful FDI project means a foreign investor taking out more hard currency than is brought in over the life of the investment project.

Until recently, the overall approach of Ethiopia’s government with respect to FDI could be described as cautious. It strove hard to attract FDI into export-oriented sectors but was resistant of FDI into “strategic” sectors such as telecoms and banking. The casual links are very clear and simple: if the country lets in FDI into non-tradable sectors, the investors would make their profits in Birr but would legally repatriate profits in foreign currencies.

Given the high profitability of these sectors in growing economies like Ethiopia, the total amount of hard currency that non-national investors repatriate out of the country would be much larger than the amount they originally brought in. Since these sectors hardly directly earn foreign currency, the currency that the investors would take out of the country in the form of after-tax profits would have to come from other sources, such as coffee exports or earnings from tourists.

Therefore, even if it appears that inflow of large amounts of FDI - say through privatisation of Ethio telecom to foreign companies - would temporarily alleviate the hard currency shortages of the country, it is very likely to worsen the balance-of-payments problems of the country in the mid- to long-term.

The challenge of worsening the balance-of-payment problem due to the inflow of FDI into non-tradable sectors is not limited to the “strategic” sectors. For instance, Dangote Cement began operations in 2015 in Ethiopia with a 600-million-dollar investment and soon topped the market.

In 2017, the company reported that Ethiopia was its most profitable market. Since the company almost exclusively sells its products manufactured in Ethiopia within the country, its profits are in Birr whereas it repatriates its profits in hard currencies.

Even if the company decides to re-invest its profits within Ethiopia, that will merely postpone its demands for hard currencies from Ethiopia to the future. This is because reinvestment of profits earned in Birr will enable it to accrue more profits, again in Birr, which it will eventually want to repatriate in hard currency at some point in the future.

A similar case could be made about the booming foreign investment into production of beer for the Ethiopian market, where some of the biggest international brands initially paid handsomely to buy state-owned beer factories. For instance, Heineken entered the Ethiopian market in 2011 following the acquisition of Harar and Bedele breweries and it quickly expanded production capacity.

By 2015 it had already built an additional factory on the outskirts of Addis Abeba and rolled out an expansion project to further boost production a year later. The fierce competition among the major global players such as Heineken and Diageo in the Ethiopian beer market demonstrates both the current and expected future profitability of this non-tradable sector.

This does not bode well for the balance-of-payments of the country since these companies will eventually repatriate their profits in hard currencies. Again, re-investment of their profits in other non-tradable sectors of the Ethiopian economy would just compound and postpone the problem.

There is an important lesson here. Even if the prevailing development orthodoxy claims otherwise and advocates for the attraction of FDI, historical evidence amply demonstrates the fact that the capital required for economic development has to be largely generated and mobilised from domestic sources.

There is no sustainable way around the pressing shortages of hard currency in Ethiopia but to try and solve the underlying structural problems. The privatisation of lucrative public enterprises and liberalisation of so far protected non-tradable sectors would not solve the problem. In fact, it is highly likely to worsen it through mid- and long-term impact on the balance of payments.

The Ethiopian government would be well-advised to reconsider its position on FDI into all non-tradable sectors - including selling stakes in state-owned enterprises to foreign companies - and seriously study the implications of its approach to attracting FDI into non-tradable sectors on the balance-of-payments of the country.

PUBLISHED ON

Dec 25,2018 [ VOL

19 , NO

974]

Commentaries | Dec 25,2018

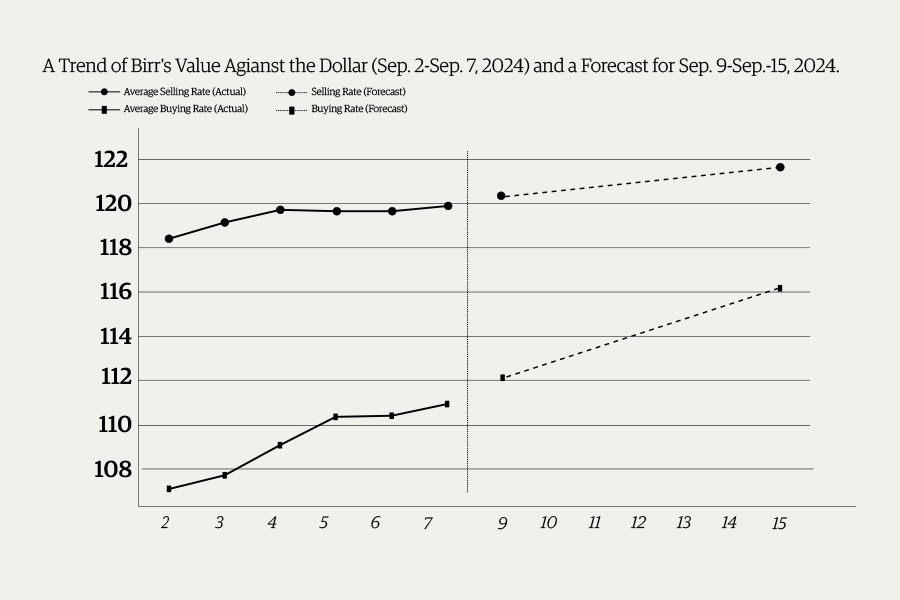

Money Market Watch | Sep 08,2024

Agenda | Oct 24,2020

Fortune News | Nov 03,2024

Commentaries | Feb 25,2023

Radar | Aug 17,2019

Agenda | Mar 05,2022

Fortune News | Mar 07,2020

Featured | Nov 16,2024

Commentaries | Dec 16,2023

Photo Gallery | 179001 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 169196 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 160072 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 137134 Views | Aug 14,2021

Commentaries | Oct 25,2025

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Oct 25 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

Officials of the Addis Abeba's Education Bureau have embarked on an ambitious experim...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The federal government is making a landmark shift in its investment incentive regime...

Oct 29 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) is preparing to issue a directive that will funda...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A community of booksellers shadowing the Ethiopian National Theatre has been jolted b...