Fortune News | Apr 06,2019

Businesses in the floriculture industry thought they had seen the worst when the COVID-19 pandemic hit two years ago. In the months following the outbreak, they took a hit as lockdowns and travel restrictions put a chokehold on demand in their largest market – Europe. The Netherlands bought 294 million dollars worth of flowers last year, claiming a little over 60pc of flowers Ethiopia sold to the world in the same year.

Though the virus left hardly any industry unaffected, floriculture felt the sting the hardest as flower producers source inputs abroad. There is almost no option to substitute chemicals, fertilisers, and seeds from the domestic market. This is not for lack of attempt. Floriculturists had tried their hand at sourcing from local suppliers as these, together with royalty payments, account for 90pc of spending in foreign currency to run a flower farm.

Afri Flower, in Holeta town in Oromia Regional State, 40Km west of Addis Abeba, saw firsthand the futility of turning to local suppliers. The company grows roses, spray roses, and gypsophila on its farm in a region favoured by floriculturists for its conducive climate. It had tried to buy packaging materials here, but the gap in quality remains a barrier. Afri Flower executives had to scramble to import it instead.

As the pandemic progressed and restrictions began to ease, the industry breathed a collective sigh of relief. Not for long, though.

In the year since, the industry has been plagued by a series of hiccups, each seemingly tougher than the last.

In January, the central bank decided to alter foreign currency retention and distribution rules for the third time in a year. Commercial banks have to surrender 70pc of export revenues and remittances to the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE). What is left is to be shared between exporters and banks. There is also a percentage to go to cover freight costs. Exporters' share in forex retention dropped by half to 20pc.

For exporters, this meant profoundly altering the business calculus. Many entered the export sector, hardly making money from what they sold. Previously, they had been allowed to retain 30pc of export earnings unbounded by time, and 10pc to be used in 28 days of receipt, after which it had to be surrendered to the central bank. The catch was to import merchandise the local market is desperate to find. The margins from imports can even cover the losses from export transactions.

Exporters received the news of the dropping share in forex retention coldly. Little did many suspect they were in for some more disappointments.

Federal government officials and regulators at the central bank were desperate to beef up the country's foreign currency reserves, which may pay for a little over one month of imports. To cover the ballooning import bills, feared to reach 18 billion dollars this year, and external debt payments, bordering 1.6 billion dollars, they have also tried to discourage the use of foreign currency for the imports of what they categorise as "non-essential goods."

Over the first half of the year, the government spent 2.1 billion dollars on the import of basic goods and a further one billion dollars on external debt servicing. In the face of dwindling loans and grants from development partners; surges in the prices of essential commodities such as wheat, fertiliser, and petroleum; and a global shipping crisis, the government's attempt to hold on to as much forex as possible remains a source of frustration for the officials watching on the balance of payments.

In attempting to patch an economic wound in the absence of an adequate fallback, their policy response ensued a ripple effect that whacks a segment or two of the economy. Exporters find themselves at the receiving end of the series of policies meant to increase the foreign exchange reserves.

Sentayehu Kebede, general manager of Afri Flower, is one of those who find the current rules on forex retention hard to swallow. It has made it more difficult for him to run a business that employs 500 people. Afri Flower has paused monthly royalty payments to the patent owners of the high-quality flower seeds it uses. Suppliers are showing reluctance to continue with the credit-based payment system they had had with the company for years. Some are refusing to accept new orders, Sentayehu said, with a tone of vexation in his voice.

Hawassa Industrial Park, the largest of its kind in the country, accounted for 41pc of the 177.4 million dollars generated by companies operating in industrial parks last year. Issues with forex and trade restrictions could see the figure decline this year.

"They're asking us to switch to a cash-against-document scheme," said the General Manager.

The timing of the central bank's decision could not have been more off for Afri Flower and several in the floriculture industry. This was a season of peak sales in the year. Valentine's and Mother's day merrymakings bring with them a swell in demand, sometimes as much as 40pc. The over 100 floriculture companies, which grow flowers on 1,600ht of land, rush to leverage the moment.

The industry could also be a victim of its own success. Despite the forex policy its leaders view as detrimental, and in apprehension, it has done well. It brought in 471 million dollars last year, covering 13pc of revenues from export Ethiopia generated. Export revenues from flowers exceeded traditional sources such as khat (11pc), oilseeds (nine percent) and pulses (seven percent).

Over 2,700tn flowers were exported over the first two weeks of February, a report from the Ethiopian Horticulture Producer Exporters Association (EHPEA) reveals. Data from the Customs Commission shows flower export revenues hit 55 million dollars over the past two months alone, recording a 10pc increase on last year's same period figure.

Another input-intensive industry impacted by the new rules is the textile industry. Industry insiders ring the alarm bell that productivity has been declining in recent months, perhaps due to the retention policy changes.

Elias Tesfaye Garment & Textile Factory runs two plants in the Akaki-Qality District and Bishoftu town. Operating with 1,400 employees, the company generates around three million dollars a year, shipping its products to North America, Europe and the Middle East. Its productivity has fallen by a fifth since the retention rates were changed, according to Elias Tesfaye, a major shareholder.

"We're working with what we had in stock before the regulation changed," he told Fortune.

Elias says that accessing letters of credit (LCs) from commercial banks has become more difficult. Queues for LCs are long, and the fast-moving manufacturing sector is ill-suited for extended waits.

Like many other manufacturers, Elias hopes to see his industry receive a preferential surrender rate. After all, it generated 147 million dollars in earnings mainly exported to the United States, claiming 4.7pc of total exports. Nonetheless, the industry had seen revenues dropping by 13pc from the previous year when it had generated 169 million dollars. But the outlook for the first half of the current year gives those in the industry like Elias a cause for sanguinity. The industry brought in 75 million dollars, an increase of 15pc from the same period last year. So has the share of textile export revenues jumped by one percentage point.

Experts like Ermias Wodajo, a private consultant having experience with industrial parks companies, say bargaining on retention share will do little for manufacturers.

"It wouldn't be enough even if it had been 50pc," he said.

Ermias advises exporters and the government to find alternatives to source raw materials.

Textile manufacturers operating in industrial parks have not been spared the trouble either.

Tenants there use two operational modalities. Through Free on Board (FOB) shipment, apparel manufacturers take care of everything from raw material procurement, product development, and sampling to production, managing orders and shipping products to destination ports. There is also the cut, make and trim (CMT) modality, where buyers pay for the inputs and the manufacturers are paid in foreign currency for the production. The payment normally amounts to 30pc of total export value.

Companies operating in the 13 industrial parks generated 177.4 million dollars in export revenues last year, a 7.5pc growth. Those in the Hawassa Industrial Park brought the largest share, accounting for 41.2pc of the earnings.

Hibret Lemma, chief executive officer (CEO) of the Hawassa Industrial Park Investors' Association, noticed companies in industrial parks increasingly rely on the CMT scheme.

A study conducted by the central bank, the Ethiopian Investment Commission (EIC), and the Association on the forex use of 12 companies that make up 90pc of the Park's export revenues discovered that those using the FOB scheme had spent 137.9pc of the forex earnings on operational costs over the past four years. It is insufficient to cover overhead costs, and they have had to visit banks to get forex. The figure is 33pc for CMT users.

Raw material imports, salaries for expatriate staff, and rental fees are the main expenses covered in foreign exchange.

Businesses in the Park have been pleading for a preferential forex surrender rate since the central bank first altered the rules a year ago. Their pleas remain unanswered. The rules may have been introduced as "temporary measures", but they are to stay at least until the end of the year, disclosed Fikadu Digafe, vice governor and chief economist of the central bank.

The central bank will not entertain any requests for preferential treatment in adjusting retention rates, the Vice Governor told Fortune.

Spurned by the central bank, the 23 companies operating in Hawassa have tried to cut a deal with the Industrial Parks Development Corporation (IPDC). They want to pay rent in local currency. Companies pay 2.5 dollars a square metre in rental fees. The smallest shed available in Hawassa Industrial Park is 2,275sqm in size, while the largest is 44,000sqm.

Paying in Birr could make a retention rate of 50pc sufficient to allow manufacturers to run feasibly, Hibret argued.

Neither would the news from the Corporation delight the companies. Its executives prefer to keep things as they are, says Sandokan Debebe, chief executive officer of the IPDC. Acknowledging the companies' misgivings about the retention rules, he believes the rental fees at industrial parks are "low".

"Changing the currency would undermine the financial viability of the Corporation," he said.

However, the Corporation could consider adjusting prices in local currency if it is the only way forward, Sandokan told Fortune.

His view seems to be influenced by a decision the central bank made recently, allowing companies in industrial parks to pay rent in Birr, Fikadu disclosed to Fortune.

It is only that the decision is yet to be enforced. However, the IPDC is unaware that such a decision has been made, according to Sandokan.

Though the change will provide some relief to the manufacturers, other factors such as Ethiopia's delisting from the African Growth & Opportunity Act (AGOA) worries those in the textile industry. Two companies in Hawassa Industrial Park have shut down over the past two months, and a couple more might follow suit, says Hibret. He fears the impacts of President Joe Biden's executive decision and the forex shortage can be more visible next month when companies start the order and input cycle anew.

Experts like Ayele Gelan, a macroeconomist at the University of Strathclyde in the UK, argue in favour of sector-specific measures to help retain exporters' earnings. But this is a symptom of larger economic problems whose policy response should be found elsewhere.

"Exporters should be allowed to retain all their earnings," he said.

Yet, the revised retention rates have helped the federal government add close to 400 million dollars to its coffers over the past two months.

"It's not a lot, but it helped us cover rising expenditures," said Fikadu.

This may mean little to exporters like Afri Flower waiting with bated breath for better days ahead. However, many are less than confident about their prospects.

"The industry has a few months left before it gets completely stuck," Sentayehu warns.

PUBLISHED ON

Mar 05,2022 [ VOL

22 , NO

1140]

Fortune News | Apr 06,2019

Radar | Oct 06,2024

Fortune News | Jul 13,2020

Agenda | Aug 11,2024

Radar | Oct 06,2024

Commentaries | Feb 27,2021

Editorial | Jul 18,2021

Fortune News | Jul 24,2021

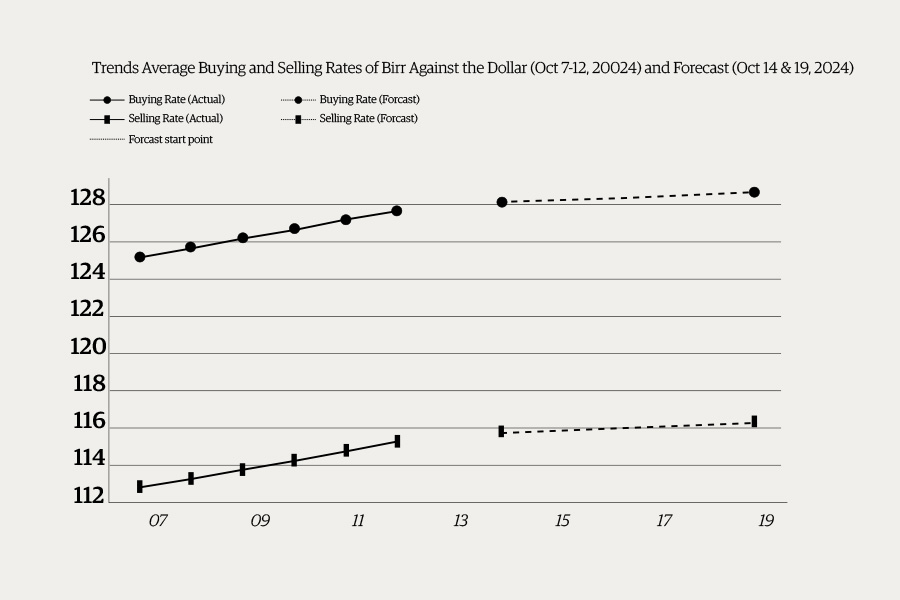

Money Market Watch | Oct 13,2024

Radar | Sep 10,2023

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 5 , 2025

Six years ago, Ethiopia was the darling of international liberal commentators. A year...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jun 14 , 2025

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars...