Commentaries | Aug 22,2020

Jul 24 , 2021

By Habtamu Yesigat (PhD)

In Ethiopia and across much of sub-Saharan Africa, farmers are being sidelined as a result of a lack of a robust agro-processing industry that would turn raw materials into processed products with a longer shelf life. Government and private sector collaboration is key to strengthening this link, building rural economies, and generating jobs desperately needed for pandemic recovery, writes Habtamu Yesigat (PhD), Ethiopian agricultural development economist with extensive research experience in Africa and Europe, director of programmes for Precision Agriculture for Development and Aspen 2021 New Voices Fellow.

While traveling from Hawassa, currently a capital to both the Southern and Sidama regional states, to Addis Abeba last March, I met a tomato producer on the roadside looking for buyers. His regular trader had skipped travel to the farm to collect the harvest for the last two weeks. The farmer, therefore, set out to sell his tomatoes on the street and was worried that the harvest could be wasted.

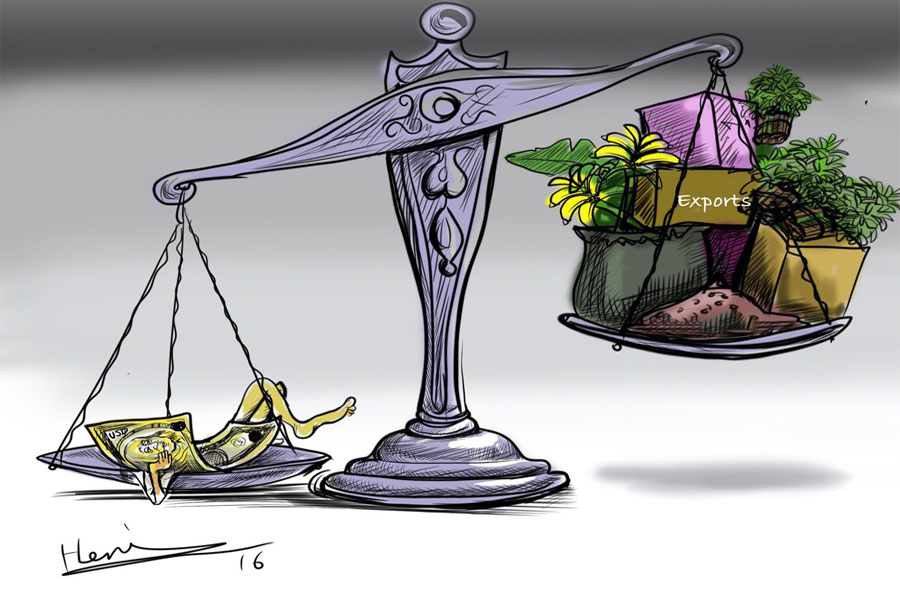

This is the experience of most smallholder farmers. They have little knowledge about the market situation when they make production decisions. Disconnected from the market, they rely on the middle-person; there is no processing plant that they know of; and in the end, they are hit with low prices and a lack of market outlets. Meanwhile, instead of local brands, expensive processed food imports line many supermarket shelves. Perhaps unsurprisingly, I had an imported brand of tomato paste for a snack in my backpack as I talked with the farmer.

In Ethiopia and across much of sub-Saharan Africa, farmers are being sidelined in a dysfunctional agricultural system with a weak link: lack of a robust agro-processing industry that would turn raw materials, such as tomatoes, into a processed product, such as tomato paste, with a longer shelf life. Such an industry would purchase locally, absorb large harvests, and ensure farmers a market. Government and private sector collaboration is key to strengthening this link, building rural economies, and generating jobs desperately needed for pandemic recovery.

Indeed, the COVID-19 pandemic makes the situation even more urgent. Even a few weeks of travel restrictions could depress agricultural trade, lead to lower prices for the farmer and drive-up food prices for urban consumers, according to Farmers Weekly. Indeed, between January 2020 and June 2021, global food prices rose 40pc. The number of people facing acute food insecurity and needing urgent assistance hit a five-year high in 2020. Small-scale farmers who are stuck with spoiled or unsold harvests are among those most affected. The post-harvest loss in tomatoes in Dire Dawa, for instance, accounted for about 45pc of the total production, according to a study conducted in 2018. Ethiopia and many African economies are predominantly agrarian, and such losses impact the larger economy.

Countries are hit with a double burden. On the one hand, farmers’ produce is left unsold or sold for pennies. On the other hand, there is no adequate supply of fresh and processed agricultural products in the market. At the same time, many countries import food products.

This begs the question: if the demand for processed agricultural goods is there, what hinders private sector development?

Companies are put off by the challenges: fragmented production, low and variable quality raw materials, and underdeveloped transport. This all adds up to extremely high risk for every dollar invested. And it presents this dilemma: unless there is an adequate supply of standardised farm products, quality grading systems, and a functional infrastructure, the private sector will not find agro-processing an attractive business proposition.

Farmers, on the other hand, will not find large-scale production feasible as long as they continue to rely on the existing unreliable market conditions.

There is a way out. Government co-investments with the private sector could lower risk. Co-investments that support coordination between businesses and farmers would be particularly effective. Governments could help farmers to organise and produce more as a group, provide timely and reliable market information, and support contract farming activities. In addition, this coordination activity would support standardised quality and adequate supply of agricultural products for processing plants.

Public-private partnerships in agro-processing are already proving their worth. For example, Ghana attracted over 37 million dollars in private funds through a provision of numerous incentives for Ghana Rubber Estates. The government supported this initiative through the development of infrastructures and facilities (construction of farm and feeder roads), activities to help farmers (credit provision, contractual agreements, subsidised insurance and an income protection fund in case of low rubber market prices), and actions to support businesses (guarantee for quality raw material, tax breaks).

Recently, a public-private partnership between the Kebbi State government in Nigeria and GBfoods established a 48 million dollar tomato processing factory. In its first three years, the tomato factory has contributed to improved incomes for smallholder farmers that supply fresh tomatoes to the processing factory. Farmers were provided with improved seeds, fertilisers, training and irrigation pumps.

Selling a few tomatoes at a time on the roadside is a recipe for poverty. Well thought out, designed and executed public-private partnerships that build agro-processing capacity would allow farmers to earn, save and invest more and put affordable local brands on grocery shelves. If Africa wants to achieve food security, enable its farmers to prosper, and generate jobs, governments and companies should invest in public-private partnerships that forge unbreakable links between farmers and markets.

PUBLISHED ON

Jul 24,2021 [ VOL

22 , NO

1108]

Commentaries | Aug 22,2020

Agenda | Mar 19,2022

News Analysis | Sep 10,2021

Fortune News | Jun 18,2022

Viewpoints | May 23,2021

Agenda |

Fortune News | Jun 25,2022

Agenda | May 13,2023

Commentaries | Mar 19,2022

Fortune News | Dec 28,2019

Photo Gallery | 97252 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 89474 Views | Apr 26,2019

My Opinion | 67332 Views | Aug 14,2021

Commentaries | 65811 Views | Oct 02,2021

Feb 24 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

Abel Yeshitila, a real estate developer with a 12-year track record, finds himself unable to sell homes in his latest venture. Despite slash...

Feb 10 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

In his last week's address to Parliament, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) painted a picture of an economy...

Jan 7 , 2024

In the realm of international finance and diplomacy, few cities hold the distinction that Addis Abeba doe...

Sep 30 , 2023 . By AKSAH ITALO

On a chilly morning outside Ke'Geberew Market, Yeshi Chane, a 35-year-old mother cradling her seven-month-old baby, stands amidst the throng...

Apr 27 , 2024

The Prosperity Party (PP) - Prosperitians - is charting a course through treacherous...

Apr 20 , 2024

In a departure from its traditionally opaque practices, the National Bank of Ethiopia...

Apr 13 , 2024

In the hushed corridors of the legislative house on Lorenzo Te'azaz Road (Arat Kilo)...

Apr 6 , 2024

In a rather unsettling turn of events, the state-owned Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (C...

Apr 28 , 2024

A dire situation unfolds across public universities, where students face the harsh re...

Apr 28 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

A European business lobby in Ethiopia issued a scathing review of the tax system last...

Apr 28 , 2024

The Federal Supreme Court has recently ruled in the prolonged commercial dispute surr...

Apr 28 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

Transport authorities placed blame on driving schools and vehicle inspection centres...