Feb 1 , 2025

By Abdulmenan M. Hamza

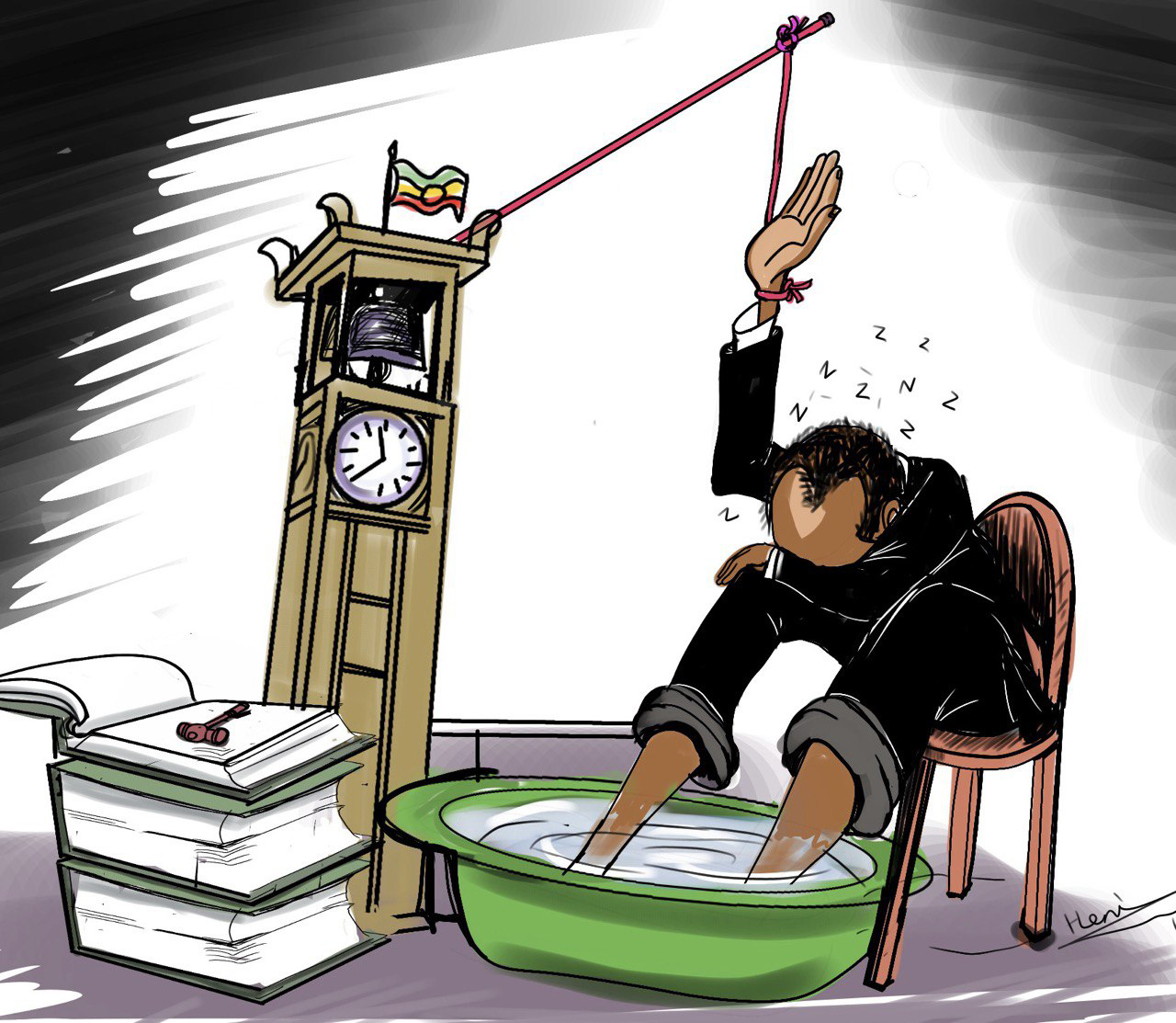

For one-and-a-half decades, Ethiopia’s state-led economic growth model generated impressive expansion in gross domestic product (GDP) but left behind a series of financial and structural complications. The grand vision of transforming the economy’s fundamentals never progressed beyond rhetoric, and the ambitious structural changes that policymakers promised remain elusive. While recent reforms have been introduced with much fanfare, their outcomes are still unclear. They have yet to alter the country’s economic reality meaningfully.

A well-developed financial system is a key driver of any robust economy. It goes beyond simply disbursing credit to established businesses. As the economist Joseph Schumpeter argued, banks fuel growth through what he dubbed “creative destruction.” It involves channelling funds toward risk-taking entrepreneurs who introduce novel products, adopt unconventional production processes, and break into untapped markets.

This process of disruption makes resources available for innovators, and such a financial system has the potential to propel economic development to new heights.

Ethiopia’s experience demonstrates what happens when that system fails to do its job.

Entrepreneurship and access to finance are the most critical elements in economic development. A vibrant system for protecting property rights and financing new ventures promotes the formation of businesses that can bring fresh ideas to the marketplace. Developed economies long ago established institutions such as equity markets, pension funds, and insurance companies that cater to ventures of all sizes. These structures have given businesses a lifeline and a robust ecosystem for seeking diverse forms of capital.

However, banks dominate the financial sector in much of the developing world, including Ethiopia. Relationships, insider information, and collateral arrangements often influence decisions about who gets credit. This approach generally benefits established traders and property developers over small manufacturers or agricultural enterprises, which traditional metrics deem too risky.

Over the years, private banks in Ethiopia have leaned heavily on relationship-based lending. This has meant that entrepreneurs, especially those with untested ideas or technology-driven concepts, find themselves outside the circle of favoured borrowers. When domestic banks step up, they typically demand collateral that many young or innovative companies do not possess. Even manufacturing firms with assets fare poorly in this environment, owing to fears of market volatility or logistical challenges. Agriculture, crucial as it may be for national food security, also struggles to win bank financing because of seasonal uncertainties, weather risks, and infrastructure gaps.

To compensate for the shortcomings of these private banks, policymakers turned to state-owned financial giants. The Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (CBE), the country’s largest lender, poured billions of dollars into public infrastructure, including power generation, railway lines, and mass housing projects, while the Development Bank of Ethiopia (DBE) extended loans to private companies in agriculture and manufacturing. Yet, political interference in financial institutions took its toll.

Non-performing loans (NPLs) accumulated to alarming levels, raising fears of a domino effect that could destabilise the wider financial system. In a move that would have caused political firestorms in more transparent economies, Ethiopian authorities quietly took over a massive portion of CBE’s bad loans last October. The absence of public debate or legislative scrutiny exposed the governance gap, revealing the risks of depending on institutions without sufficient checks and balances.

The outlook for the country’s entrepreneurs is incredibly bleak.

Across the world, startups that disrupt established markets turn to venture capitalists or private equity investors who can look past immediate collateral requirements and instead value innovative potential and long-term growth. Ethiopia lacks these alternative funding mechanisms. It has also been nearly impossible to tap capital markets because there have been no functioning stock exchanges where new companies could list their shares and attract investors who might diversify across different industries.

In the past two decades, a handful of entrepreneurial ventures attempted public share subscriptions to raise equity, but the results were largely disastrous. Many of these businesses vanished within a few years, leaving investors with valueless certificates and eroding public trust in share offerings. The lack of oversight over such ventures, combined with unscrupulous operators looking to make a quick profit, led to a spate of failures. This brought deep scepticism among Ethiopians, many of whom came to see share subscriptions not as an investment in the future but as a high-stakes gamble.

Hopes ran high when federal authorities launched the Ethiopian Securities Exchange (ESX) after years of planning. Projections suggested that about 50 companies, mainly from the financial services sector, would list their shares and inaugurate a new chapter in the country’s capital markets. However, details of which companies will appear on the exchange remain unclear. The stringent listing requirements set by regulators protect investors from dubious operators, yet they also raise the bar high for legitimate entrepreneurs lacking extensive track records.

That irony has tempered some of the initial excitement as policymakers struggle with balancing investor safeguards and the need to provide fresh avenues for capital formation.

Broader economic and political uncertainties continue to cast a long shadow. Firms of all sizes remain wary of bureaucratic delays, arbitrary decisions by local officials, and corruption that can sap the energy of the most ambitious startups. Property rights, another crucial element in building confidence, still need to be strengthened to assure investors that the rules of the game will not shift overnight. Corruption, often experienced at the local level where permits and licenses are granted, blunts innovation and steers capital toward unproductive channels.

Overcoming these hurdles demands a new financial architecture that identifies, evaluates, and funds new ideas rather than defaulting to tried-and-tested ventures. Mortar and brick banks, whether public or private, should reinvent themselves if they are to stay relevant. The state can also create space for more specialised funding platforms, such as venture capital firms and private equity funds, while regulators can encourage a culture of accountability to build trust in capital markets. Such structural changes become even more urgent in a political environment prone to sudden shifts that push investors toward speculative activities instead of productive enterprises.

The years ahead will show whether the long-promised transformation can take hold. Policymakers have begun to acknowledge that relying on heavy government intervention and relationship-based financing will not deliver the entrepreneurship or productivity gains the economy needs. Yet, without stronger institutions, better regulation, and more openness to risk-taking, the economic reforms may prove little more than a fleeting attempt at change.

The potential is enormous, but so is the tough call to turn a notoriously insular financial system into a catalyst for growth and innovation.

PUBLISHED ON

Feb 01,2025 [ VOL

25 , NO

1292]

My Opinion | 132151 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 128561 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 126482 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 124091 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 12 , 2025

Political leaders and their policy advisors often promise great leaps forward, yet th...

Jul 5 , 2025

Six years ago, Ethiopia was the darling of international liberal commentators. A year...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The Addis Abeba City Revenue Bureau has introduced a new directive set to reshape how...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Addis Abeba has approved a record 350 billion Br budget for the 2025/26 fiscal year,...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By RUTH BERHANU

The Addis Abeba Revenue Bureau has scrapped a value-added tax (VAT) on unprocessed ve...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Federal lawmakers have finally brought closure to a protracted and contentious tax de...