Money Market Watch | Dec 29,2024

Dec 28 , 2024

By Million Kibret

From Ethiopia's attempt to reform systemic distortions to Kenya's aim to balance currency fluctuations with interventions, both countries demonstrate the need for robust strategies to spur economic growth and protect the vulnerable. As they continue to evolve, it isn't only about whether the currency floats or is policy-guided, but it should also be about policymakers' effectiveness in leveraging broader strategies. writes Million Kibret, a managing partner at BDO Ethiopia.

At the close of 2024, two East African neighbours offer an intriguing lesson in contrasting foreign exchange policies.

After years under a managed floating system, Ethiopia shifted to a market-determined regime in July, hoping to close the persistent gap between official and black-market rates. Kenya, by contrast, has long operated a floating exchange rate, granting its currency, Shilling, the flexibility to move with market forces and relying on regulatory interventions to cushion shocks.

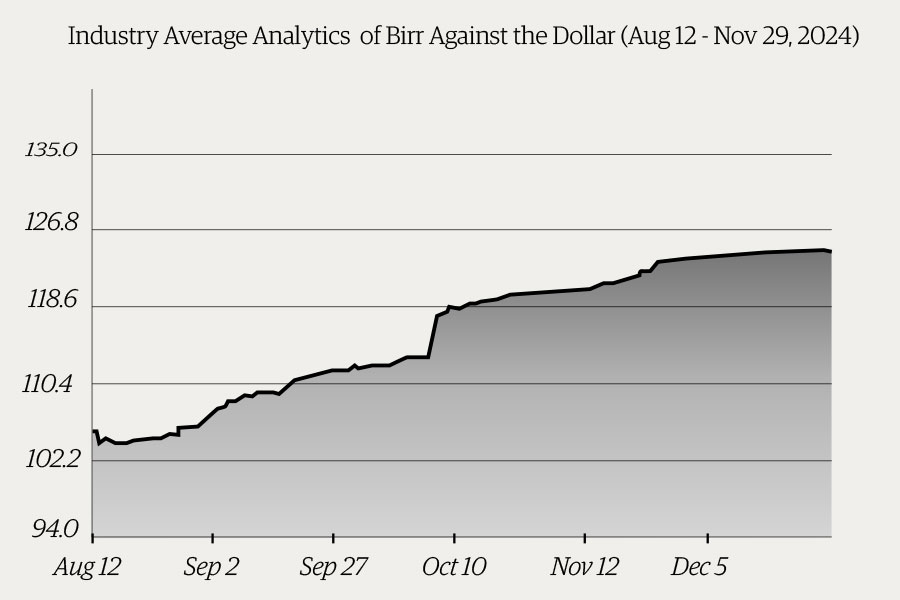

Ethiopia's forex regime reforms were as dramatic as they were ambitious. Policymakers scrapped the managed floating rate and let the Birr (the Brewed Buck) seek its level based on supply and demand. Within weeks, the Birr lost over 103pc of its official value. By mid-December, it was traded at 125.41 Br against the U.S. Dollar (the Green Buck), much closer to the rate quoted in informal markets.

On paper, the policy shift had the precise objectives of bridging the gap between the official rate and the parallel market, attracting more remittances, and encouraging a more transparent foreign exchange environment. Its authors have also aspired to attract foreign investment, a critical component of the home-grown economic reform agenda.

While officials defended the move as essential to resolving deep structural imbalances, there is little doubt that higher consumer prices are testing households and small businesses in a country that has endured other disruptions, including conflicts and the ongoing fallout from the Russia-Ukraine war. Liberalising a currency in an economy heavily relying on imported goods invites serious inflationary risks. Ethiopia depends on external inputs ranging from fuel to machinery; devaluation quickly drives up prices for local consumers.

For many, the cost of everyday staples has jumped, echoing the government’s admission that inflationary pressures were an inevitable short-term consequence of the policy shift. By November, annual inflation reached 16.9pc, a noticeable climb from 16.1pc the previous month.

Limited export diversification compounds the challenge. Africa’s second-most populous country export basket is dominated by coffee, oil seeds, and cut flowers, which jointly account for a substantial share of foreign exchange earnings. Theoretically, a weaker Birr should encourage export growth by making goods cheaper abroad. However, with such a narrow range of export products, exporters struggle to take full advantage of the depreciated Birr.

For coffee farmers, depreciation can mean higher local returns once foreign exchange is converted, but the broader economy remains vulnerable to fluctuations in global commodity prices and competition from other emerging markets. Policymakers bet on remittance inflows, reporting that it improved as Ethiopians working overseas took advantage of more favourable exchange rates. They feel accomplished seeing the gap between official and parallel market rates narrowed, weakening the incentives to trade on the unofficial market. They hope that, over time, enhanced transparency will facilitate more stable capital inflows.

Nonetheless, they also conceded that keeping inflation at bay would require carefully calibrated measures, possibly including further monetary tightening and a renewed focus on industrialising beyond traditional commodity exports.

Across the border to the south, the Kenyan Shilling trades under a floating regime that has long been praised for granting the market a decisive voice in setting prices. The Shilling has depreciated steadily over the past two years, by 22pc against the Dollar beginning in March 2022. Yet, the movement has been relatively orderly. As of December 20, 2024, the exchange rate was 129.29 Shillings for a dollar.

Kenya’s Central Bank has often signalled that while the currency is free-floating, it does not relinquish intervention when volatility occurs. Indeed, the monetary authority’s benchmark interest rate has seen multiple adjustments this year before settling at 11.25pc in December, a level intended to maintain price stability while avoiding a sharp brake on growth.

Despite currency swings, Kenya’s inflation rate has remained low by regional standards. A slight uptick to 2.8pc in November kept it comfortably below its neighbour's. Kenyan officials attribute this stability to favourable food harvests, stable fuel costs, and disciplined monetary policy.

A robust pipeline of official reserves also helped. In July 2024, Kenya’s forex reserve was reported to be 7.4 billion dollars, enough to cover roughly four months of the country's imports. Several factors bolstered these reserves, including deferred payment arrangements for oil imports that spread the foreign exchange burden over a longer horizon. The government’s decisions have also benefited from support programs by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), helping Kenya remain resilient despite a global backdrop of tighter financial conditions.

The Central Bank’s balancing act is evident. Maintaining foreign exchange reserves is essential for dampening shocks, but it can become costly if reserves slip below the recommended threshold. Officials are keenly aware that while the Shilling has proved resilient, global disruptions, such as conflicts in Europe, trade disputes, and tighter monetary policies in developed markets, could all take a toll.

Kenya’s approach has yielded other dividends.

High yields on local currency bonds have piqued the interest of investors seeking a blend of yield and relative stability. Fiscal authorities have managed the delicate balance of public debt and made steady progress in keeping the Shilling stable enough to attract foreign participation. However, persistent concerns remain over whether Kenya can maintain these policies despite periodic external shocks. Droughts, floods, and occasional political unrest pose risks to agricultural production, a mainstay of the economy.

Though the World Bank cut growth forecast for Kenya to 4.7pc for 2024, officials in Nairobi say the medium-term outlook remains encouraging if infrastructure improvements and regulatory reforms stay on track.

The free movement of the Shilling has become a hallmark of the country’s open business climate. Foreign firms find it relatively straightforward to convert earnings and repatriate profits. Exporters benefit from the stability that allows them to plan for production and shipping costs with little fear that a sudden currency intervention would erode profit margins. Kenya’s diversified export base, which includes tea, horticulture, apparel, and services, has helped the economy maintain a steady flow of foreign exchange, though it is not entirely insulated from external turbulence.

For Ethiopia, currency liberalisation signalled an official effort to correct systemic distortions. The official exchange rate had been pegged too far from market realities, creating a breeding ground for speculative arbitrage and scarce inflows. Bringing the Brewed Buck's official value in line with street prices not only removed a disincentive for foreign investors but also made monetary policymaking more transparent.

Nonetheless, the struggles with a lack of foreign reserves have not vanished overnight. The federal government still relies heavily on remittances to meet short-term forex needs, and the ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine has pushed energy and grain prices higher, placing additional strain on households. Officials stress that external debt management should go hand in hand with currency reform, backed by IMF programs providing technical support and financial buffers.

Ordinary Ethiopians, meanwhile, face the immediate consequences of a sharply weaker currency. Importers who bring in everything from electronics to medications complain that costs are skyrocketing. Small businesses contend with more expensive raw materials, leaving them little choice but to pass on at least some of the higher costs to consumers. Social safety nets remain spotty, although the government has pledged targeted assistance for the most vulnerable populations, including subsidies on certain essential goods.

Unless they broaden the manufacturing base and strengthen the domestic value chains, currency liberalisation will have limited benefits for average citizens. Efforts to develop agro-processing and light manufacturing are ongoing. It may take time before they yield enough foreign exchange revenues to cushion the economy from global price shifts.

While the interplay between exchange rate policy and inflation is often abstract, it has a tangible effect on families. In Ethiopia, the pinch of higher import costs is felt most acutely by those in urban areas, who rely on foreign goods or subsidised commodities. Coffee growers in the rural highlands may see some benefit from favourable export prices, but the rising cost of fuel and inputs for processing and transport can offset those gains.

For Kenya, stable inflation translates into less volatility in household budgets. Even small shifts in fuel or food costs can ripple through the consumer price index, yet the country’s broad supply chain and foreign partnerships help mitigate those shocks. Government officials argue that strategic deals with Gulf oil suppliers, which reduce near-term dollar outflows, will continue to stabilise the market in the months ahead.

On the geopolitical front, these countries wrestle with external uncertainties that can ripple through currency markets. Ethiopia’s predicament is magnified by domestic political and security unrest, as well as global energy and commodity price swings. The war in Ukraine, for instance, has pressured supply chains for wheat, metals, and fuel. Higher import bills for these goods exacerbate Ethiopia’s forex shortfalls, undercutting export gains from the weaker Brewed Buck.

Kenya, though better positioned, also faces rising costs for energy products, even if global oil prices remain below their midyear peaks. Kenyan officials try to offset these pressures with timely interventions in the foreign exchange and treasury markets. Yet, they cannot eliminate the possibility that persistent global shocks could push inflation higher and slow growth.

The most apparent lesson from the divergent paths of these neighbouring countries is that exchange rate regimes on their own cannot fully determine economic outcomes. Ethiopia has leapt toward a market-determined exchange rate to correct chronic distortions, yet success depends on broader policy measures. Advancing industrial projects, diversifying exports, and resolving political tensions will be critical if Ethiopians are to reap any lasting benefits from a more transparent currency mechanism.

Kenya’s floating regime, while generally lauded, has limitations. The Shilling is susceptible to fluctuations in international markets, though the Central Bank’s careful management and comfortable reserve position have prevented excessive volatility.

Investor sentiment appears cautiously optimistic about both countries, although the reasons differ. In Ethiopia, the big draw is the prospect of a sizeable domestic market coupled with new clarity in the foreign exchange system. Multinationals and private equity firms may see an opportunity for high returns if they can overcome the regulatory burden and uncertain political terrain. In Kenya, confidence is rooted in the proven track record of a government that balances a floating currency with interventions, ensuring a measure of predictability. While the World Bank’s revision of Kenya’s GDP forecast dropped it to 4.7pc, urging caution, major players in agriculture and infrastructure say the country’s fundamentals remain strong.

Officials in both countries emphasise that foreign exchange policies do not operate in a vacuum. They tie into everything from social welfare to national security. Policymakers in Addis Abeba argue that their decision to free the Birr aligns Ethiopia with global financial norms. In time, they hope this could attract diversified investment into the manufacturing sector, renewable energy, and services. Kenyan authorities, mindful that no currency regime is foolproof, insist their flexible approach will keep the country well-positioned to respond to unexpected shocks. They point to initiatives such as the deferred oil payment plan and robust deals with multilateral lenders as evidence that prudent foresight can stabilise the Shilling.

Though each country's next phase is uncertain, exchange rate policy is an indispensable but incomplete tool for achieving long-term development and financial stability. Ethiopia can claim the short-term victory of narrowing official and black-market rates, though it faces an uphill battle to expand its economic base. Kenya can point to its capacity for weathering global storms, but it, too, confronts ongoing fiscal pressures and the ever-present risk of external shocks.

As both countries demonstrate, a currency’s path is less about whether it floats or is guided by the state. It is more about how effectively policymakers leverage broader strategies to spur economic growth, keep inflation in check, and protect the most vulnerable citizens from the brunt of market turbulence.

PUBLISHED ON

Dec 28,2024 [ VOL

25 , NO

1287]

My Opinion | 131548 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 127903 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 125879 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123510 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jun 14 , 2025

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars...

Jun 7 , 2025

Few promises shine brighter in Addis Abeba than the pledge of a roof for every family...

Jun 29 , 2025

Addis Abeba's first rains have coincided with a sweeping rise in private school tuition, prompting the city's education...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Central Bank Governor Mamo Mihretu claimed a bold reconfiguration of monetary policy...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal government is betting on a sweeping overhaul of the driver licensing regi...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Gadaa Bank has listed 1.2 million shares on the Ethiopian Securities Exchange (ESX),...