Commentaries | Mar 20,2021

Jun 27 , 2020

By Fisseha Adugna

In the course of negotiations over the GERD, Egyptian leaders have utilised cherry-picked arguments with different audiences and succeeded in creating confusion about the real issues at hand, writes Fisseha Adugna, former ambassador of Ethiopia to the United Kingdom & Northern Ireland. The opinion reflected here is solely his own and not that of any institution or government.

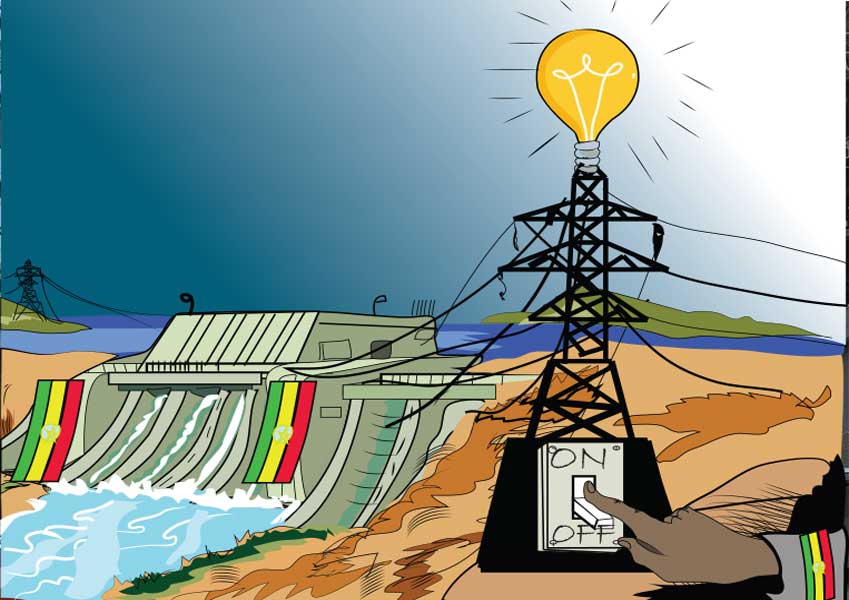

The dramatic events between Ethiopia and Egypt over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) have only been unfolding faster over the past few weeks as Ethiopia prepares to begin filling the reservoir in July.

The good news was the resumption of stalled negotiations and the extension of an invitation to the European Union, the United States and South Africa to serve as observers. Then Sudan announced that progress had been made, with 95pc of the open issues resolved, but Egypt kept pushing back on the lack of progress.

On June 19, 2020, the Egyptian Foreign Minister wrote a letter to the UN Security Council pleading for its intervention in the dispute “which potentially constitute[s] a threat to international peace and security.”

Ethiopia, for its part, rejected Egypt’s allegations and expressed its plan to go ahead in filling the Dam with or without a deal.

“For us it is not mandatory to reach agreement before starting filling the Dam, hence we will commence the filling process in the coming rainy season,” Foreign Minister Gedu Andargachew told The Associated Press.

In the course of this long negotiation, Egyptian leaders have utilised cherry-picked arguments with different audiences and succeeded in creating confusion about the real issues at hand. Sometimes technical issues such as the safety of the Dam or its management principles during prolonged droughts are the core of Egypt’s argument.

In other instances, negotiations have focused on colonial treaties, acquired rights and maintenance of the status quo. And then in yet other discussions, arguments are centered on unsubstantiated and largely fear-based conjecture about the Dam's possible impact on Egyptian agriculture.

There are Egyptians who believe their leaders use the GERD negotiations as a pretext to suppress domestic dissent. The government has banned press coverage on the GERD, which indicates a desire to deny the Egyptian people balanced information from independent sources.

Egypt has employed extensive resources to reinforce its game plan for the GERD and Nile waters. They have carried out diplomatic and propaganda campaigns against Ethiopia. They knocked on every door in the corridors of world leaders in order to bring third-party pressure against Ethiopia. They hired famous lobbying and PR firms to influence foreign leaders and public opinion in the West.

The objective of all of these was primarily image building for Egypt after its international standing suffered immensely. This was due to a violent military coup against the first democratically elected president of the country and the subsequent bloody crackdown of human rights and civil society activists in Egypt.

The other responsibility of these powerful firms is to help distance Ethiopia from its traditional allies during this long and sensitive dispute.

On the propaganda front, Egypt has two seemingly contradictory approaches. On the one hand, Egypt portrays itself as an aggrieved party fighting for its survival and as a victim of Ethiopian cruelty; cruelty that will deprive Egyptian people of water from the Nile. On the other hand, Egypt threatens Ethiopia and indicates that it will use its military might if the East African country does not budge, portraying itself as the policeman of the Middle East and Africa.

The people of Egypt and Ethiopia developed two great civilisations that have lived side by side for millennia. They are connected by the mighty Nile, and they aspire to live in peace together. However, there are also instances where Egyptian leaders have exhibited imperial ambitions to weaken and dominate Ethiopia, an attitude which has sometimes been manifest in their modern bilateral relations.

The modern Egyptian state is linked to Mohamed Ali Pasha, the Albanian-Ottoman governor who became powerful and established his own dynasty in Egypt. Starting in the 1820s he began his adventure by conquering Sudan and attempted to move further south.

Ethiopia, as the source of the Blue Nile, was the main target. Ali Pasha’s grandson, Khedive Ismael Pasha, was the leader who tried to implement Egypt’s ambition to control the source of the Blue Nile. He unleashed two devastating battles against Ethiopia – Gundet and Gura - in the mid-1870s. Egypt lost both.

Khedive Ismael sent his son, Prince Hassan, to lead the expedition at Gura, whose account has shaped Egypt’s behavior in their relationship with Ethiopia. It would be quite hopeless for the Khedive to try the conquest of Ethiopia, according to what the Prince told his father after he was captured and pardoned by Emperor Yohannes IV.

Gura was consequential for Egypt. Egypt lost 4,000 men and 8,000 rifles at the Battle of Gura. Apart from the shame that the Khedive suffered at the hands of Ethiopians, that military adventure resulted in a financial and political crisis for the Khedive. The Khedive was deposed in 1879. Egypt could not pay back its British creditors, opening the door for the United Kingdom to colonise Egypt in 1882. Egyptian adventurism in Ethiopia badly weakened the Turco-Egyptian administration in Sudan and caused the rise of the Mahdi Movement in 1881.

The British occupation of Egypt remained in place from 1882 to 1956. While Britain was still in Egypt, a military coup took place in 1952 that toppled the monarchy and helped establish a military state in Egypt. Successive Egyptian leaders continued advancing their ambitions over Ethiopia.

In 1956, Gamal Abdel Nasser became the president of Egypt. He financed liberation movements to weaken Ethiopia. President Sadat continued a policy of intimidation and declared in 1978 that he would go to war with Ethiopia if the country built a dam on the Blue Nile.

More recently, the former Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi threatened to attack Ethiopia in order to stop the construction of the GERD.

Morsi and his cabinet suggested three actions, namely “sending special forces to destroy the dam, sending jet fighters to scare the Ethiopians,” and “called for Egypt to support rebel groups fighting the government in Addis Abeba,” according to the BBC in 2013.

The current president of Egypt, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, initially spoke about cooperation among Nile riparian countries, which seemed like a change in the traditional Egyptian policy that focused on depriving the rights of the other riparian states to use their water resources. That was welcomed by many, but soon enough el-Sisi broke his promise and rejoined his predecessors in pursuing old uncompromising rhetoric on the Nile.

On June 20, 2020, el-Sisi visited an air force base in western Egypt and told his pilots to be ready for any mission, potentially outside the borders of Egypt. It was just a day before that he accused Ethiopia for the lack of progress on the GERD discussions and disrupted the latest negotiations.

Egypt has continued to frustrate any meaningful cooperation on the Nile. In February 1999, the Nile Basin Initiative (NBI) was launched, which was supported by external actors such as the World Bank. The Nile Basin covers 11 countries with a combined population of about 300 million people comprised of Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Tanzania and South Sudan. The objective of NBI was “to achieve sustainable socio-economic development through the equitable utilization of Nile Basin water resources” among all riparian countries.

A decade ago, after nearly 11 years of negotiations on the framework of the NBI, most countries signed the Cooperative Framework Agreement (CFA), but Egypt refused to. The desire to establish a permanent Nile River Basin Commission, which would serve as a permanent legal and institutional framework for governing the Nile River Basin, thus did not materialise.

Since 2012, Ethiopia has begun construction of the GERD and at the same time also commenced dialogue with Egypt and Sudan. Sudan signed on and joined Ethiopia from the beginning, appreciating the many benefits the project would bring to the downstream countries. Egypt was less forthcoming, and its position changed from time to time, often proposing unreasonable demands that delayed progress. Egypt’s consistent delay tactics through nearly a decade of negotiations can only be understood as an attempt to frustrate and weaken the progress of the Dam with the eventual expectation of influencing the outcome.

After many ups and downs, Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan finally signed a “Declaration of Principles (DoP)” in Khartoum on March 23, 2015, and have begun negotiations to implement that agreement. Negotiations were going on when Egypt, on August 1, 2019, suddenly submitted a new proposal that, in effect, sidelined the agreement on the Declaration.

This new proposal brought back Egypt’s long-time argument about the protection of colonial and bilateral “water-sharing treaties” that exclude all water source countries. It overlooked the fact that the Nile is a transboundary river which has 11 riparian countries. Such a frustrating position is a deliberate and well-thought-out tactic on Egypt’s part.

After the submission of this proposal, Egypt began unprecedented diplomatic and public relations campaigns aimed at pressuring Ethiopia through diplomatic blackmail, threats and intimidation tactics designed to force Ethiopia to accept the latest proposal.

Egypt focused on Ethiopia’s allies to pressure Ethiopia, and that seemed to have gained a short-term PR victory for Egypt. However, those PR and lobby campaigns were ultimately ineffectual. Instead of persuading Ethiopia’s longtime allies to take punitive action against Ethiopia for refusing Egypt’s unreasonable demands, the international community largely opted to urge the two countries to engage in direct negotiations to resolve their differences.

In fact, instead of galvanising international public opinion against Ethiopia on the GERD, Egypt helped to popularise the GERD. This was demonstrated by the responses that came from the United Nations Secretary-General and the European Union to Egypt’s accusations against Ethiopia. They both emphasised the resumption of negotiations to resolve differences through dialogue and understanding. The responses from the African Union and the Nile riparian countries went even further, saying that Egypt should not invite outside forces to African problems that should be resolved by Africans.

How long will Egypt pursue such destructive tactics?

Egyptians will undoubtedly confront multiple projects on the Nile by many countries shortly, and they cannot hope to manage these developments through intimidation, blackmail and tirades.

Egypt's policy on the Nile is a zero-sum policy. It aims to maintain the status quo. Its war-like propaganda to advance its policy objectives is dangerous for our region. They cannot scare 10 riparian countries into not using their water resources. They have to play a positive role and work with others in the spirit of cooperation and good neighbourly relations.

Perhaps current Egyptian leaders can learn from the Camp David Accords. President Anwar Sadat was a flawed leader, but his courage in bringing about peace with Israel was appreciable. The country achieved through peaceful negotiation what it could not achieve through military means. Because of the Accords, Egypt has enjoyed long periods of peaceful relations with its powerful neighbour.

More importantly, it regained the Sinai Peninsula and has become a long time recipient of generous economic and military assistance from the United States. Such is the kind of courage which is needed on the Nile River. One cannot hope to gain sustainable peace and prosperity by refusing cooperation with 10 riparian countries in the Nile Valley. Leadership that aims for short-term popularity by misleading its people through fear, intimidation and the gross exaggeration of the impact of the GERD on their lives is not good leadership for the long term.

PUBLISHED ON

Jun 27,2020 [ VOL

21 , NO

1052]

Commentaries | Mar 20,2021

My Opinion | Sep 30,2023

Editorial | Feb 26,2022

Fortune News | Feb 16,2019

Viewpoints | Jan 25,2020

Radar | Apr 24,2021

Viewpoints | Jul 03,2021

Editorial | Aug 26,2023

Radar | Feb 23,2019

Radar | Nov 28,2020

My Opinion | 131499 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 127855 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 125833 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123463 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jun 14 , 2025

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars...

Jun 7 , 2025

Few promises shine brighter in Addis Abeba than the pledge of a roof for every family...

Jun 29 , 2025

Addis Abeba's first rains have coincided with a sweeping rise in private school tuition, prompting the city's education...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Central Bank Governor Mamo Mihretu claimed a bold reconfiguration of monetary policy...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal government is betting on a sweeping overhaul of the driver licensing regi...

Jun 29 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Gadaa Bank has listed 1.2 million shares on the Ethiopian Securities Exchange (ESX),...