Radar | Mar 25,2023

Like so many children who grow up wanting to be a doctor, Tariku Hussen (MD) had his heart set on the medical profession from a young age. He had good grades and encouragement from his aunt who had supported him through school. But the decision to become a doctor took a lot of consideration. He knew that he would have to commit the next seven years of his life to school, which generates minimal pay only during the graduating class.

It was a difficult choice to make but one he ended up making with resolve; hoping that once he was finished with his studies, things would fall into place.

In a country where there is only one physician for every 10,000 people, according to a report by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), employment for a doctor seemed as good as guaranteed.

However, as graduation loomed closer, Tariku understood that his chances of finding a job were not as secure as he had once imagined.

"I knew this was coming before I graduated," said Tariku, who had served as president of the Ethiopian Medical Association at Gonder University. "We were having dialogues with the Ministry of Health at the time to resolve similar issues for our seniors who were having difficulty [securing jobs]."

He says he was not prepared for how bleak it really was.

"It wasn't that there weren't enough job posts," he said. "It was that there were no posts at all. It was demoralising to realise I wouldn't get a job after all this time."

So he volunteered to work at Eka Kotebe General Hospital for three months. His time there proved valuable as he met senior doctors who helped him get a job.

"It was difficult to find myself without a source of income after all those years," he said, "and to find out I wouldn't be able to get a job because of a language barrier and other issues was heartbreaking."

"As a doctor, you take care of an enemy's wounds," he said. "That is the moral obligation we have, but somehow I couldn't find a job, because I wasn't from a particular place in the country."

Though Tariku may have found work now, his earlier predicament is still the reality for hundreds more across the country. Last year, graduates found themselves at the height of the problem. A letter addressed to the Health Ministry regarding the rising joblessness of doctors amassed over 450 signatures in less than a week's time last August.

The practitioners have been out of work since graduation — for some, unemployment has lasted nearly a year. The problem has affected doctors from all parts of the country, with over half hailing from Amhara Regional State.

The hiring process has been difficult for many as most jobs require an additional language to be able to serve in that state, according to Gedefa Kindu (MD), who had been one of the coordinators seeking a response from the government. Applying for a job in private health institutions also comes with its own challenges, as private institutions demand experience.

For many years prior, graduating medical students were assigned to posts in different parts of the country by the Health Ministry. The centralised delegation was done based on the needs and capacity of the regional states. In 2019, this system changed and doctors were directed to look for job posts from regional health bureaus instead.

"This was why there were more doctors looking for jobs in Amhara Regional State," Gedefa said. "In some cases we encountered, being from the region itself was required."

There were also doctors who had received job offers by Tigray Regional State but had opted to decline. The current political impasse between the Regional State and the federal government had created a sense of unease among the graduates, and they had chosen to return to their hometowns.

But without a unified job post portal, it was difficult to know which posts were available.

Around 450 graduated doctors signed a letter addressed to the Ministry of Health requesting an answer for the current state of unemployment in the country last August.

"We don't know if any regional states have any open posts if it's not out in public," said Gedefa.

Stories of alleged bribes to secure posts, rigged entrance examinations, and unspecified criteria for job posts that led to an arbitrary selection became rife.

Tariku Belachew, deputy head at the Amhara Regional Health Bureau, cited budgetary constraints as its main limitation.

The region of 22 million inhabitants had tacked on an additional 162 million Br to the 300 million Br that was allocated to salaries of health professionals last year. Even so, it was only able to take in half of the 600-plus doctors that had applied for the posts.

"The demand and the resources available for hiring more doctors aren't balanced," said Tariku. "This is becoming an increasingly difficult problem, which didn't exist a few years ago. "

The deputy director attributes this to the differences between the rate of health institutions being built and the rate of professionals matriculating from schools. The region currently has 81 functional hospitals with seven more under construction.

"As per the population, we need 210 hospitals," he said. "But there is no shortage of doctors within the health facilities available in the region."

The region is conducting an assessment to evaluate the structural needs of the health facilities and the professionals needed within.

Currently, 50,000 health professionals, from health extension workers to specialised doctors, are operating in the Regional State. It has 862 health centres in which the Bureau is pushing for doctors to get hired, but budgetary restraints are also visible here.

"We're trying to get the weredaadministrations to allocate a greater share of their budgets to this," he said.

Discussions on medical employment and budgetary constraints were taking place before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Joint meetings involving the Jobs Creation Commission, the Ministry of Health, 15 members of the Ethiopian Medical Students Association, as well as the Centre for International Reproductive Health Training, had started, but efforts were put on hold once the pandemic appeared in March.

When Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) called on retired and in-training medical professionals for national duty two weeks after the onset of the pandemic, it had seemed that the country might find itself in desperate need of health professionals.

By July, nearly 23,000 health professionals had been committed to the cause in isolation and quarantine centres. Overall, the pandemic had created new job opportunities for 4,000 health professionals including recently graduated doctors. They were called into work on a contractual basis, with terms ranging from three to six months, subject to renewal if the need so dictated.

This relief, however, is proving to be short-lived.

COVID-19 quarantine and isolation centres are closing up following government policy changes geared toward isolation and self-care at home. A number of doctors have already been told that their services are no longer needed. With just a few days remaining on their contract, some are awaiting renewal, while others have already started looking for other options.

Kaleab Ashebir (MD) has applied for a teaching post, a general practitioner post at a private hospital, and the annual residency programme for graduates in the hope that one will stick.

"We've been told that they'll redeploy us, but I'm looking at other alternatives in case that doesn't work out," he said.

He had been working at the Ethiopian Youth Sports Academy, which had been converted into an isolation centre. After working there for five months, contracting the virus himself while in service, he is now scouring the options left available to him.

Doctors are also exploring their options overseas. Establishment of an international testing centre is one of the requests of professionals who are out of jobs. The closest testing centre for the United States Medical Licensing Examination, a certification accepted in the United States and other parts of the world, is in Kenya, an unfeasible option for many.

The lack of rising joblessness among doctors may have gotten worse since last year, but the symptoms had started appearing long before.

Regional health bureaus began requiring additional language skills and mentioning budgetary constraints, according to Tegbar Yigzaw (MD), president of the Ethiopian Medical Association.

"It's a paradox," he said, "that we need at least five to six times more health professionals in the country, yet we have doctors without jobs."

The Association has been working to find a solution with the government and other non-governmental bodies like Jhpiego, a non-profit with over four decades of experience in the health sector internationally.

"The country needs to increase its spending on healthcare," he said, "and the number of its health professionals."

Ethiopia is a signatory to the Abuja Declaration, where heads of African states pledged to allocate at least 15pc of their annual budgets toward the health sector. In 2001, 12 years following the agreement, the World Health Organisation found that only Tanzania had managed to follow through on the budgetary promises. Ethiopia and 11 other countries were categorised as countries showing insufficient progress, allocating less than five percent of its annual budget.

There are other problems that also need fixing, according to Tegbar.

After demanding a high grade-point average from students wishing to enter medical school, requiring them to complete seven years of training and education is commensurate to wasting resources, stated Tegbar.

Another issue raised is outdated structural operations that are not modeled on the work burden shouldered by caregivers in the sector. This leaves health professionals overworked and patients waiting in unbearable queues, explained Tegbar.

"We're operating under an outdated staffing norm," said Tegbar. "Hospital services are different now. You [should] give more time to communicating with patients."

Health centres, which used to have general practitioners assigned to them, no longer do. Placing doctors across the more than 3,000 health centres in the country will take in many professionals and tenure better healthcare at lower levels, according to Tegbar.

"People that use these centres also deserve good healthcare," said Tegbar.

During the Ministry of Health's previous assignment system, doctors were forced to choose between completing multiyear service posts or paying a hefty fee to obtain their practitioners license. However, this was changed as the number of health professionals in the country increased, according to Lia Tadesse (MD), Minister of Health.

"Graduated doctors had been caught in the middle of the back and forth," she told Fortune. "The Ministry assigns them to a region, and the region sends them back with a response of no budget."

In response to this, the government lowered the required payment and started availing practising licenses to doctors so they could explore other options.

Another change made was to the residency programme — previously financed by the employing hospital, costs are now being covered by the federal government, according to the Minister.

"This was to encourage hiring by hospitals," she said. It became effective last year with a budget totaling upwards of 100 million Br.

Currently, the Ministry is revising the standards for health institutes in the country, including the option of assigning doctors to health centres. Though it will require an additional budget, the Ministry is working on trying to find innovative ways to manage budgetary expansion without depending on donors, according to Lia.

"Sustainable health financing is one of our main objectives in the coming five years," said Lia. "Although we've been steadily increasing the budget for health, we've yet to reach the intended goal."

This year, a little over 19 billion Br was allocated to the health sector, a jump from the 12 billion Br of the previous year.

Governmental agencies cannot absorb all the graduating practitioners, as this is not a long-term solution, according to the Minister. Here, too, discussions are taking place between the Jobs Creation Commission, the ministries of Innovation & Technology and Health.

"We need to create a conducive environment for the private sector to engage," she said. "In addition to that, we're working on enabling the practitioners to open consultancy offices where they can work in collaboration with other institutes."

Though regarded as a last resort, the Ministry is also considering sending professionals outside the country.

"We'll be disclosing more details on plans regarding this in two weeks," she said.

Sending professionals outside the country is the final option to take while the country has an immense need for health professionals, according to public health experts like Tewabech Bishaw (MD), founder of Alliance for Brain Gain & Innovative Development.

"There are countries like Cuba who have an agreement with other nations and allot a certain amount of their health professionals toward that goal," she said. "Perhaps this is something that the government can explore if all other options are exhausted."

Tewabech, who also serves as the secretary-general of the African Foundation of Public Health Associations, believes that to make informed decisions, there is a need for accurate data sources and a better understanding of the currently employed workforce in the country.

"The marketability and demand of the sector had initially led policymakers to flood it with professionals," she said, "in an attempt to match the needs of the country."

But that has now resulted in a misalignment of budget and capacity. The finance, health and education sectors need to be on the same page, according to the expert.

"The health policy in the country needs to get the attention and priority it deserves," she said, "as this isn't putting resources toward a consumer. It's investing in the economic development of the country."

Health institutes are complex and need a lot of resources to function. This creates delays in their retention capacity and the speed with which they can create jobs and provide services to the public, according to her.

"This goes beyond just the question of employment and as far as the protection of basic human rights to health," said Tewabech.

PUBLISHED ON

Oct 31,2020 [ VOL

21 , NO

1070]

Radar | Mar 25,2023

Fortune News | Jun 07,2020

Sunday with Eden | Jun 07,2025

Fortune News | Oct 12,2019

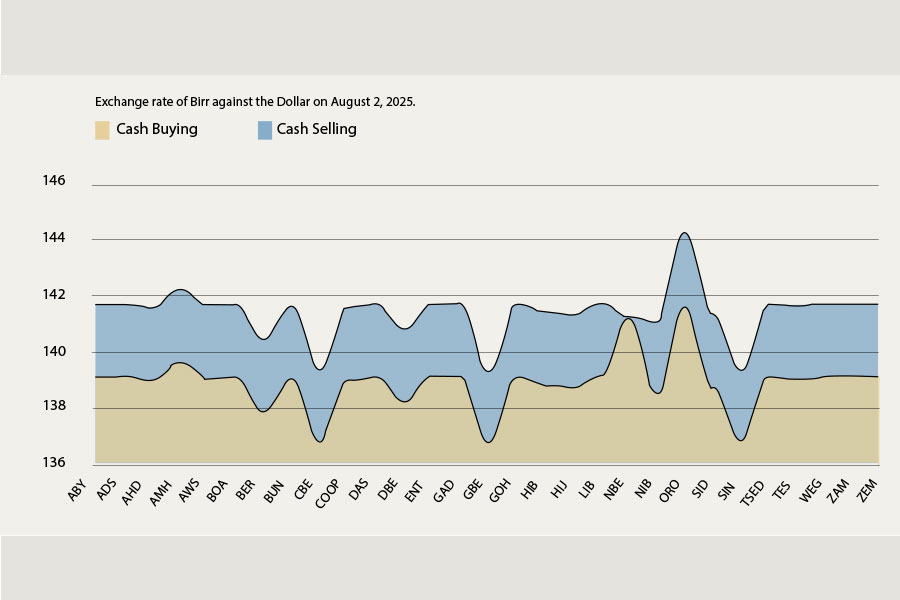

Money Market Watch | Aug 23,2025

Obituary | Jun 17,2023

Obituary |

Agenda | Aug 01,2020

Fortune News | Dec 10,2022

Obituary | Oct 12,2019

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...

Sep 20 , 2025

Getachew Reda's return to the national stage was always going to stir attention. Once...