Fortune News | Dec 27,2018

Nov 30 , 2019.

Finally, officials at the central bank acted upon repealing one of the most controversial policies of an activist state. Two weeks ago, the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) announced the lifting of the 27pc bond private banks were mandated to buy, forcing them to rechannel resources they mobilised to sectors in the economy the state prefers.

In place since 2011, the justification for this policy move has gone this way. Private banks are unlikely to finance risky investment ventures in priority areas the government has designated as crucial to the national economy. The state-owned Development Bank of Ethiopia (DBE) was chosen to be the financing vehicle to receive one-third of deposits by private banks and funnel it into what policymakers consider high productivity sectors, such as manufacturing.

It was not all doom and gloom. There was a silver lining in the cloud. Over the past eight years, around 116 billion Br was mobilised, and most of it was used to finance mega-development projects that are essential to upgrade the country’s infrastructure. Most certainly, manufacturing plants, mostly of Turkish origin, benefited from the loan largesse, leading the DBE to be cynically nicknamed the "development bank of Turkey."

Though it might not have achieved what it was intended for - entirely - it is not wise to dismiss the problems this policy tried to address. They remain real and should not be discounted outright.

There was a need to tighten the money supply to rein in galloping inflation. In the face of little national savings, there was a reason to find ways of better deposit mobilisation and allocation. Though some of it might have been based on ideological conviction, the allegation directed at the private sector’s lack of appetite for risk-taking in long-term projects was not entirely unfounded. It is only stating the obvious to recall that the developmental state needed a way to finance the mega projects that are at the core of its ambition to create an aggregate demand where there was little capital and meagre national savings.

However, there is little doubt that all that was achieved was at the high cost of crowding out the private sector from accessing credit.

It is the tenet of "developmental stateism" to be suspicious of the private sector. Despite its sometimes ugly predatory instincts, there is no economy anywhere in the world that has sustainably shown dynamic growth without the active participation of the private sector. This is true even in China, as well as in many of the Asian tigers.

In theory, even the EPRDFites have repeatedly stated, in their ideological documents, their ultimate goal was to get the private sector to be a significant player in the economy. Though their paranoia about the business class never allowed them to take it fully onboard, some might argue that this is just the time they have always intended: time for the private sector to step up.

Now there is an administration in power shifting such a rigid worldview on how the economy should be managed away from an activist state to one run by the active role of the private sector. The new party made from the debris of the EPRDF, the Prosperity Party (PP), is liberal in its economic policy formation, as it is emerging as a centre-right force in its political orientation.

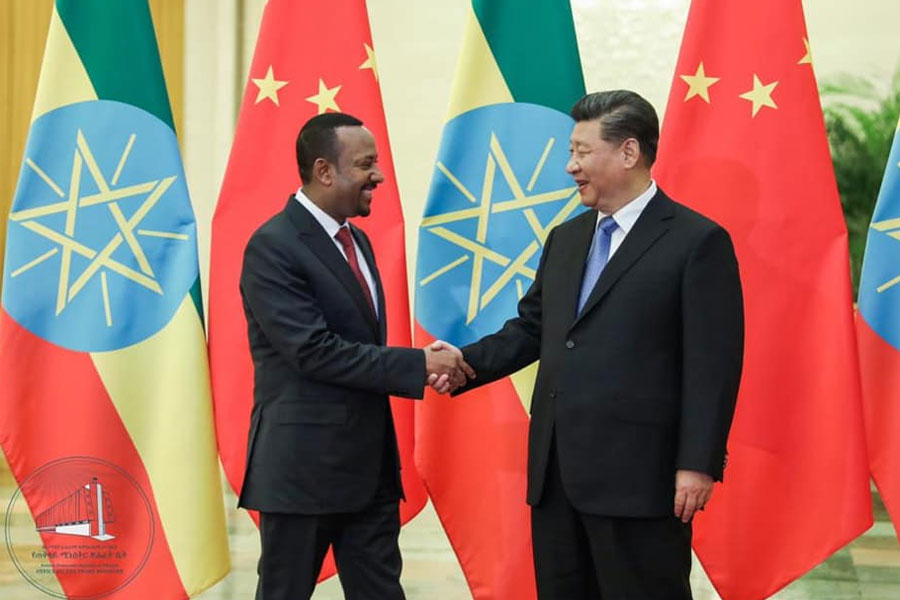

Whatever the ideological arguments, the lifting of the bond is the most unambiguous indication that Abiy’s administration is walking the talk in allowing the private sector to play a leading role in the economy. Even more significant was the fast-tracking of the investment bill that liberalises industries such as in finance, aviation and logistics.

The three-year Homegrown Economic Reform Programme could not be any more explicit in its private sector friendliness. The administration is betting the family farm on the private sector. They must not fail this administration and the country at large at this historical junction.

Leaders of the private sector have long complained about the little space the activist state has afforded them and its intrusive, suffocating regulations. They will not have a better time than now to prove their critics wrong and deliver a meaningful contribution to the country’s development while turning in profits to their shareholders. They must prove the two are not mutually exclusive.

A dynamic and innovative private sector alive with entrepreneurship-having the right kind of thoughtful policy support and incentives from the state-can take the economy a long way forward.

It gives one hope that Abiy's administration and its young policy wonks have realised this; they are taking meaningful steps in the right direction. The repealing of the directive that unjustly subjected private banks to funnel resources to a rather inept policy bank is one such step. It is not the state with the insight and competence to determine the efficient and optimum allocation of resources in the economy. It is the market operating on the basis of demand and supply with a competent and agreeable regulatory state.

Liberalisation of the economy and opening up formerly closed sectors for both domestic and global competition is another. But while liberalisation may have been a step in the right direction, it is likely to do more harm than good if it is carried out without strong and independent regulatory institutions to look after them.

While a well-trained, disciplined and professional civil service is the essential backbone of an efficient economy, including even the most liberal ones, a country just emerging from a statist system is in particular need of institutional capability. The role of such a civil service will be of make-or-break significance. The central bank is a good illustration of how institutional inadequacies could be detrimental to the wellbeing of an economy and limitations on the efficient functioning of its operators.

In the face of an onslaught of savvy international players in search of the last investment frontiers, naïve and incompetent regulators can be ripe targets for state capture. The rapid opening of formerly closed sectors in the economy has the risk of the government not having enough time to develop the required human resources, as well as the legal and institutional settings, to manoeuvre the tricky transition to an open economy. Successfully!

There is no shortage of examples of poorly handled transitions, rushed privatisation schemes or liberalisation moves.

While the policy wonks in this administration take these right steps to make room for the private sector, they should also work as hard to strengthen the regulatory capacity of the state. It will only be tragic if they are to repeat mistakes in the past of filling the civil service ranks by control freaks and innovation-stifling old bureaucrats and party loyalists. A new breed of well-informed, technology savvy and competent technocrats, who understand the importance of their regulatory role for economic growth and citizens' welfare, should be the most sought-after.

This is especially crucial in the financial sector.

It may well be essential to acknowledge and celebrate the right step taken in lifting the demand on banks to buy the mandatory bond. But it is more important to point out that the government should ensure the autonomous functions of the central bank, the professionalisation of its bureaucracy, and the disentanglement of the institution from the grip of the executive branch of government.

PUBLISHED ON

Nov 30,2019 [ VOL

20 , NO

1022]

Fortune News | Dec 27,2018

Fortune News | Nov 16,2019

Radar | Dec 10,2018

Sunday with Eden | Jun 22,2024

Fineline | May 18,2019

Fortune News | Jun 15,2019

Fortune News | Apr 26,2019

Sunday with Eden | Feb 01,2019

Radar | Feb 22,2020

Fortune News | Sep 18,2022

My Opinion | 132272 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 128692 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 126600 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 124206 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The Addis Abeba City Revenue Bureau has introduced a new directive set to reshape how...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Addis Abeba has approved a record 350 billion Br budget for the 2025/26 fiscal year,...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By RUTH BERHANU

The Addis Abeba Revenue Bureau has scrapped a value-added tax (VAT) on unprocessed ve...

Jul 13 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Federal lawmakers have finally brought closure to a protracted and contentious tax de...