Viewpoints | Jul 22,2023

On a broad range of plots on Gabon St. (stretching between Meskel Flower to Agona Cinema) lie a foundation for a five-storey building, one of many construction project sites left idle. They seem to remind passersby of a time of distress. Labourers were hardly visible as activities ceased; the usual loading and unloading of construction inputs, the noise of trucks mixing and transporting cement, and the howl from heavy machinery were quiet.

In front of the skeletons of a structure, over 50 daily labourers were gathered in an area designated to them - almost by default - ready to run and seize the opportunity when trucks loaded with construction inputs such as cement and rebar arrived. The desperate and despairing look on their faces was unmistakable.

Worku Belay, in his 40s, was one of these labourres. Eight years ago, he moved from Quarit, in the western Gojjam zone of the Amhara Regional State. He aspired to get a job and support his family back in his hometown. A father of two, Worku works as an artisan labourer earning up to 500 Br a day.

“Keeping the job becomes uncertain,” said Worku. “It’s been a week since I got work.”

Those fortunate among the labourers moonlight as security guards during the night. Even that, Mekonnen finds it too difficult to find.

The construction industry has been confounded by the shortage of materials, mainly caused by supply-chain disruptions and the unprecedented rise in prices of inputs, primarily cement and reinforcement bars, known in the industry’s lexicon as “rebar”. This puts the industry in the middle of a storm, overwhelming project owners from reaching the finishing line. The primary input for the construction sector, the cement shortage remains a nightmare for the industry, exacerbated over the past two years.

However, what has transpired over the last three weeks is unprecedented; a jam in the national supply chain has emptied stores and outlets across the capital. The chronic shortage has taken a toll on the progress of construction projects, where 20,000 contractors registered to work in the industry.

Incorporated in 2014, Ben Mcon Construction Plc, a grade-four contractor, provides construction services with over 25 permanent and up to 200 temporary employees.

Registering an average of 30 million Br in turnover, the company is handling seven projects and has completed over a dozen. Projects are no longer delivered on time, causing disputes between contractors and clients.

The famished construction industry has left workers unemployed, confounded and astray.

“We’re subjected to settle claims,” said Mubarek Nesru, the general manager.

The soaring prices have led the authorities in the trade sector to cap prices. The Minister of Trade & Regional Integration (MoTRI), Gebremesqel Chala, introduced a directive last July, which sought to end the distribution of cement through agents, instructing factory managers to sell a quintal of cement to designated distributors between 770 and 870 Br. Retail prices have surged to around 2,000 Br a quintal as wholesalers and retailers have their stocks depleted.

The 10 cement plants have an aggregate production capacity of 8.4 million tonnes annually. Demand is estimated to outstrip by four million tonnes. Derba Cement, located 70Km northwest of the capital, remains the largest factory, producing 2.5 million tonnes annually, followed by Dangote Cement, with 2.3 million tonnes. The Nigerian billionaire-owned Dangote sells directly to public projects at the factory gate for 900 Br.

It is a vital link in the value chains of the construction industry that brings the largest employment and contributes to the economy, accounting for one-fifth of the country’s GDP. About two million people got permanent jobs, and 961,000 others like Mekonnen, receive temporary employment at the end of last year.

Shortages of rebars and steel have added fuel to the tangle. The forex crunch and war in Ukraine exasperated the challenges importers faced. Domestic metal manufacturers operate below 20pc of their capacity. The hapless situation forced managers of the Metals Industry Development Institute to tell factories to collect scrap metals, primarily used for manufacturing rebars, two months ago. A kilogramme of steel costs 29 Br, while cast iron is traded at 21 Br.

Over 1,000tns of scrap metal is made available to six manufacturers, according to officials of the Ministry of Mines. Vehicles that have sustained severe damage and have served longer than 40 years are disposed of as scrap.

The Insitute determines prices, causing industry players to grumble over the tariff. They claim it does not consider the rise in prices at the current market, while the volume barely meets their demand. The Institute facilitates the supply of scrap metal based on the factories’ production capacity.

A thin galvanised steel sheet, mainly used for roofs and fences, is manufactured domestically. Feres is among the brands manufactured locally; its prices jumped by 73pc from 450 Br in only six months. Tila, an imported product, has its retail price gone up by nearly 83pc to 620 Br.

Industry insiders blame domestic manufacturers importing finished galvanised steel sheets as the main contributors to the supply shortage and price surge. They import galvanised rolls weighing five tones, and corrugate the flat sheet without recasting the products.

Established nine years ago with a paid-up capital of 20 million Br, Kora Korkoro & Nail Factory is among the companies that have seen production in decline owing to foreign currency shortages. It produces construction materials, mainly nail and corrugated galvanised steel.

The company can produce up to 500tns a month but operates below 30pc if its installed capacity. It has been two years since its managers applied to open a letter of credit (LC) from a bank. The company resorted to buying inputs from importers.

“It doesn’t meet our demand,” said the General Manager, Tesfa Eshetu.

Ethiopian Steel Plc is the manufacturer of Anbessa, which has been in business since 1996. It produces corrugated roof sheeting, mini-corrugated, and tile profiles. The company has plants in Addis Abeba, Gonder and Hawassa. It has not imported inputs for nearly two years and has stopped operation in the meantime. According to its managers, the company is closing its two factories.

The relentless pressure on prices is not confined to the main inputs for the construction industry. Other products like sand and gravel stones have seen sharp rises over the past eight months, particularly following the lifting off of fuel subsidies. A 16 cubic meter of sand increased by 10,000 Br from 17,000 Br and gravels by 81pc to 1,050 Br. A four-meter “morally”, a flat wood imported mainly from Austria and widely used in the construction industry, has doubled to 620 Br. Five-kilogram nail products are sold for 800 Br, having a 75pc jump from a few months ago.

Jemil Mohammed, 32, is a construction equipment supplier around Lafto. He provides construction materials, including corrugated sheets, metal cutting disks, nails, and metal wires.

“I’m exhausted,” said Jemil with a bleated expression. “The gravel stones and sand price hike is not getting attention.”

He believes that private construction project owners dealing with intermediaries to access cement from factories using their networks is the main reason creating turmoil in the construction industry.

According to the economist Alemayehu Geda (PhD), inflation in the economy is multi-dimensional. The war in Ukraine has widely contributed to aggravating it. Russia and Ukraine both have 15pc share of the total imported steel products.

Industry professionals complain that construction materials are not found at the same price as the week before. The cost of materials is going up every week, pushing those in the industry out of work and delaying projects.

“It’s difficult to grapple with,” he said.

Flinstones Homes Plc, a real estate developer with over two decades in the market and a portfolio of around 80 completed projects, is among the companies struggling to finish projects. The real estate developer has discontinued 20 projects due to the precarious inflation in construction inputs, according to its Deputy General Manager, Biruk Shimelis.

“Property developers should not be left to take the risk alone,” said Israel Bedaso, a real estate consultant with Worthy Homes.

He argues that projects are rarely completed on time due to limitations in project management and external factors. However, the shortage of inputs caused by conflicts has exacerbated the inflationary pressure. Several real estate companies have requested their clients to pay an upfront payment before signing up for any mortgage deals, which is inconsiderable of future price adjustments. Ongoing projects are halted, and finished homes have almost doubled in value.

Daniel Birhanu is a licensed real estate agent with a decade of experience in the industry. He saw the value of a two-storey house built on a 200Sqm plot in the Kebena area go up to 21 million, from 13.7 million, in six months.

Across the city from where Worku searched for a job last week was Mekonnen Tekalegn, 40. He, too, came to the city from Gojjam 13 years ago, trying to make a living as a day labourer. He works as a stonemasonry on one of the construction sites in Jemo St. Micheal’s neighbourhood. A father of three, he supports his family in a studio room around Ayer Tena, rented for a monthly 2,200 Br.

He works up to four days on a presumed good week, getting paid an average daily wage of 300 Br. However, the construction industry, battered by a ran away inflation and a credit crunch, gives him little hope to sustain his livelihood for far too long.

“I’m scared,” he told Fortune, the distress and fatigue visible in his body language. “I couldn’t afford to raise my children. I am left with no hope.”

PUBLISHED ON

Nov 12,2022 [ VOL

23 , NO

1176]

Viewpoints | Jul 22,2023

My Opinion | Apr 03,2021

Editorial | Sep 06,2020

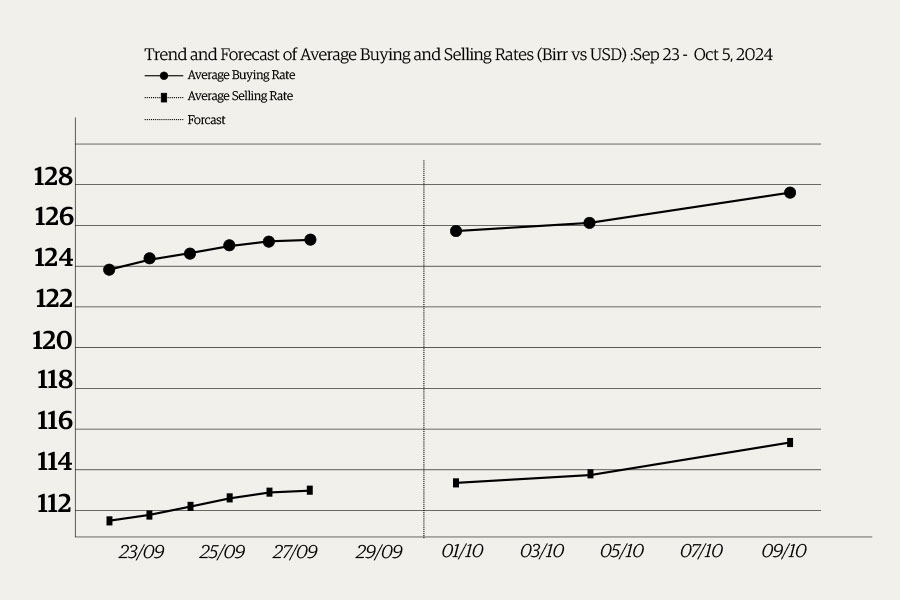

Money Market Watch | Sep 28,2024

Fortune News | Nov 18,2023

Verbatim | Aug 12,2023

Addis Fortune | May 04,2024

Radar | Aug 21,2023

Agenda | Jul 09,2022

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...

Sep 20 , 2025

Getachew Reda's return to the national stage was always going to stir attention. Once...

Sep 13 , 2025

At its launch in Nairobi two years ago, the Africa Climate Summit was billed as the f...