Radar | Oct 23,2021

On the sunny afternoon of Wednesday last week, roughly 50 health personnel on duty at Millennium Hall, once a venue for festivity, were rushing to the patient wards through the donning area. Every inch of their bodies was covered by stuffy personal protective equipment (PPE). Some were sweating profusely even before entering to see the sick and, yes, the dying, too. It showed how much strain they were under.

Stretching across the facility lie 38 wards segregated by gender, classified alphabetically. Each has a capacity of around 14 beds, and a third of the wards were occupied by patients, some on the verge of death, others fighting to recover. Almost all were on oxygen support.

The centre's four ICUs were even more chilling. Each contains a dozen or so beds, all equipped with ventilators and a team of seven or eight medical staff trying to keep patients breathing with help from the machines. Strikingly, the centre's ICU units outnumber the combined capacity of the city's four major hospitals, including Black Lion and St. Paul.

All told, 181 patients were hospitalised at the Millennium Hall on September 15, 2021. The ICUs are accommodating 47 patients, most of them unconscious. Young and old, they were lying on their beds, unaware of what was going on around them but separated from their loved ones. Eight were on tracheal intubation (TI) - a stage doctors say very few ever make it through.

Only three or four people have survived this stage since this makeshift started operation, according to Dejene Damtew (MD), a ward supervisor at the centre. He gazed at a 58-year old woman lying intubated on an ICU bed.

"She could be a mother," he said, sounding resigned to the possibility that she may not make it out of the centre alive.

Designed to accommodate around 1,000 patients, the Millennium COVID-19 Care Centre (MCCC) hosted just 12 patients two months ago. All were stable, leading to speculation that authorities were considering shutting the centre down as case numbers dropped to their lowest levels in over a year. No deaths were recorded on June 30, marking the first time since mid last year.

The scenes are worlds apart now. Cases and deaths have been climbing since mid-August, flagging the pandemic's third wave, a year and a half since it first took hold. The filling wards and intensive care units coincide with the emergence of the COVID-19 delta variant, which the US Centre for Disease Control (CDC) describes as more than twice as contagious as previous variants.

This month alone, over 22,000 cases have officially been registered, marking a 18pc positive rate, a state of affairs that coincided with the confirmation of the presence of the delta variant in Ethiopia. Some 415 people have lost their lives, while thousands of severe cases were recorded over the same period. By mid-September, over 5,000 people had lost their lives to the pandemic in Ethiopia.

To the medical staff like Dejene working at the Millennium Hall and 31 other health centres providing COVID-19 treatment in Addis Abeba, this development means a return to the heavy workload, relentless pressure, long and sleepless hours and the personal risk they were facing when the pandemic hit its peak between March and May this year. Dejene has been working in COVID-19 treatment since the very beginning of the pandemic. He started as a quarantine service provider at the Tulip Inn on Gabon Street in the Mesqel Flower area, one of the hotels chosen as a quarantine centre last year. He then moved on to Mekedonia Homes for the Elderly & Mentally Disabled before being transferred to the Millennium Hall just as the second wave took hold earlier this year.

Things were bad then; the highest-ever deaths in a single day clocked in at an unnerving 47 people on April 20, 2021.

It appears Dejene and doctors like him are back to square one lately. On September 13, just two days following the new year's celebrations, 38 deaths were recorded.

Even though the medical staff at the Millennium Hall were preparing for a third wave, what they are experiencing is more daunting than they had expected. Among the over 800 critical COVID-19 patients in the country, over 700 of them are in the capital.

There are currently 32 COVID-19 treatment centres in Addis Abeba, where 90pc of cases in the country are being registered. Eleven of these are in private hospitals and four additional private centres are awaiting approval to join.

Dejene observes young patients coming more often. One such patient was a stable 28-year man who collapsed and died just a half-hour after ending a video call with his mother.

A glance around confirms his observation.

Among those intubated was a 31-year man who had no trace of underlying health conditions but tested positive for COVID-19 when he went to a hospital looking for treatment for haemorrhoids. He was lying there as a doctor adjusted his ventilator and made his observations, unable even to see the person trying to save his life. The young man was one of many, but, sadly, it was no longer a surprise for the doctors and nurses working there, who report people in their mid-20s often succumb to the virus.

Dejene gave both the 58-year old woman the young man a day before they “X," a term the medical staff in the centre use to refer to ventilated patients who do not make it through. Sadly, he was right, both passed away hours apart the very next day. They were two of half a dozen people who die at the centre every day.

On the hopeful side, some recover as well.

One of them is Tesfaye Beyene, 48, a human resources professional who moved to the capital from Dessie six months ago.

He came to Addis Abeba with his wife and four kids. As the sole breadwinner, his hospitalisation has been hard on his family. Though his wife, sister-in-law, and their housemaid had all been infected, Tesfaye's condition deteriorated. Healthy before COVID-19 hit him, he had been at the centre for two weeks. He is well on the way to recovery and no longer requires respiratory support.

Tesfaye did not know how the virus made it into his household. But he admitted to not taking recommended precautions. Health professionals and officials alike see the surge in cases and death rates as directly tied to a drop in vigilance.

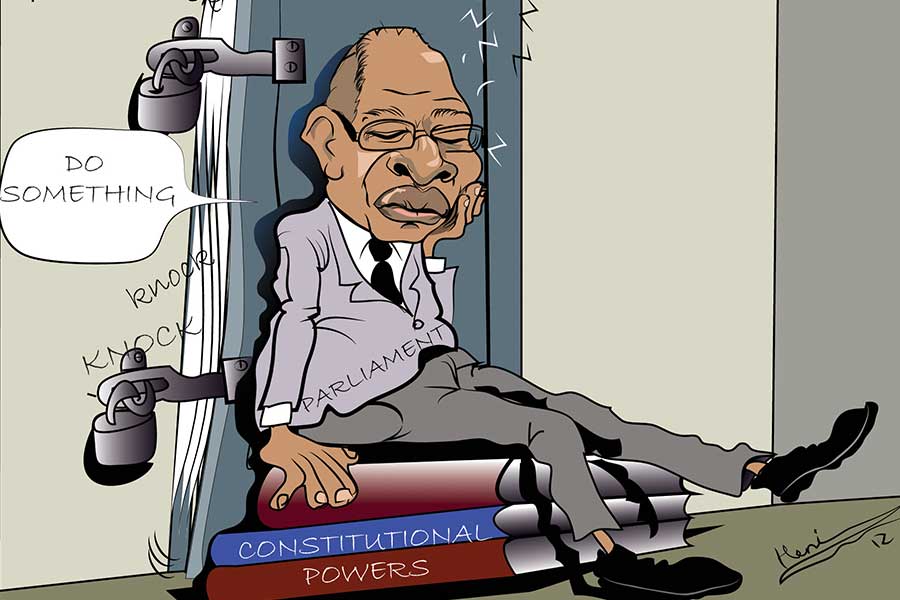

The public's response has not been adequate, says Mebratu Massebo (MD), national COVID-19 response task-force coordinator at the Ministry of Health. He asserts a lack of exemplary behaviour from political leaders, and the instability in the country has drawn attention away from the pandemic.

Mebratu's observations are obvious to anybody who has walked the streets of Addis Abeba over the past couple of months. Not many people wear face masks, large social gatherings are nothing out of the ordinary, and sanitiser has been all but forgotten. Transport service providers are also back to their usual practice of filling their vehicles up to the brim with passengers.

Biruk Wolde, a taxi driver working the route between Stadium and Shiro Meda, does not demand his passengers to wear masks.

"I got tired of it," was his response.

Of the 12 passengers on his minibus, only four were wearing their masks. Biruk himself wears a relatively clean surgical mask and keeps a bottle of sanitiser handy, while his conductor makes do with a torn-up cloth mask that he uses to cover only his chin.

"We're in discussions with law enforcement and especially the leaders of the districts to reinstate the loosened restrictions," Mebratu said.

He sees the government is buckling up to take measures with special attention to Addis Abeba, where over 90pc of recent cases were recorded.

Though the third wave is similar to its predecessor in scale, the wider availability of vaccines this time around makes the recent spike in infections a little puzzling. The first doses rolled in March 2021, just before the second wave hit. Back then, medical professionals and the elderly were prioritised to receive the jab. Since then, millions of doses have made their way into the country.

The AstraZeneca, Sinopharm and Johnson & Johnson vaccines are readily available at health centres. Anyone above the age of 18 is eligible for the vaccination, but it does not seem that many are eager to receive them. So far, some 2.4 million people have been fully vaccinated, while an additional 500,000 have received the first dose of either the AstraZeneca or Sinopharm jabs.

The figure is a far cry from the government's target to have 20pc of the population inoculated by the end of the year.

Under the leadership of Minister Lia Tadesse (MD), officials at the Ministry of Health attribute speculation among the public, whether it be rumours about side effects, religious objections, or any number of conspiracy theories, as the largest obstacle to their vaccination efforts.

Yohannes Lakew, a vaccination programme coordinator at the Health Ministry, sees suspicion about the vaccines causing blood clotting is widespread, discouraging many from getting the jab.

"The chances are one in millions," he said, underscoring the benefits far outweigh the risks. "No case of blood clotting [due to the vaccines] has been reported in Ethiopia."

While medical experts have mixed views on how officials should proceed with the situation, they are unanimous in calling the public to get vaccinated.

For Tinsae Alemayehu (MD), an infectious disease specialist, tightening restrictions and protocols to curb the spread is not likely to change much. He cites that these constraints have been slack for months and believes all efforts should be directed at vaccination instead. This could help reduce the number of patients checking into health centres with severe symptoms, according to Tinsae.

"It's crucial to get vaccinated, especially with the delta variant here," he said.

Tinsae's argument makes more sense when seen in tandem with the woefully under-equipped healthcare system. There are only 1,400 ICU beds and 1,200 ventilators for a population of over 110 million, 600 of which are located in public health centres while 200 are yet to be installed. Oxygen plants have the capacity to produce 3,285 cubic metres of medical oxygen an hour.

Yet, Tsion Firew (MD), an emergency physician and assistant professor of emergency medicine at Columbia University in New York, understands the pickle officials are in, having to choose between imposing restrictions that could put imperil livelihoods or leaving people free to go about their daily lives at the risk of more infections and more deaths.

"It's challenging to enforce lockdown measures when it puts people's survival into question," said Tsion.

Last year, the economic growth was contracted to two percent in GDP, four times lower than the average rate registered for almost a decade before the pandemic. The pandemic also left thousands jobless, especially impacting those working in the hospitality industry because of a drastic fall in tourists. The construction industry took a hit as well.

Remittance flow, a major source of foreign currency even higher than export proceeds, also dwindled by one billion dollars to 4.7 billion dollars last year after the pandemic brought the global economy to its knees.

For Tsion, even under such difficult circumstances, declaring a lockdown might be necessary to curb the spread of the pandemic, which has so far cost the government 5.7 billion Birr for the procurement of medical supplies alone. Tsion urges face masks to be mandatory for everyone while officials focus on getting as many vaccinated. Given that vaccines for communicable diseases have been commonplace in Ethiopia for nearly a century now, she believes the public should be reacting positively to the COVID-19 jabs.

"We grew up with vaccines," said Tsion.

However, even if the public decided to go all-in for the vaccines, the reality is that there would not be nearly enough to go around.

Ethiopia has vaccinated little over two percent of its population so far, a figure that pales compared to 63pc in Germany or Portugal's 81pc.

Ethiopia is not alone in the underdeveloped countries league.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), high-income countries have given 61 times more doses per person than low-income countries. Less than four percent of Africa's population has received the jab, one percentage point more than the population size vaccinated in Kenya.

The WHO reported last week that the COVAX facility's decision to slash planned vaccine deliveries to Africa would leave the continent almost 500 million doses short of its target to inoculate 40pc of the population by the end of this year.

"As long as rich countries lock COVAX out of the market, Africa will miss its vaccination goals," reads a statement from Matshidiso Moeti (MD), WHO regional director for Africa.

Despite the harsh reality, the best and only thing left to do is take advantage of the few doses available while strictly adhering to protocols. That way, lives can be spared, and the burden on the healthcare system and medical professionals like Dejene may ease slightly.

"Ethiopian health professionals should receive all the credit for fighting the pandemic with the limited resources at their disposal," said Tsion.

PUBLISHED ON

Sep 18,2021 [ VOL

22 , NO

1116]

Radar | Oct 23,2021

Commentaries | Sep 27,2020

Editorial | Jan 25,2020

Year In Review | Sep 10,2021

Commentaries | Oct 16,2021

View From Arada | Jun 14,2025

Featured | Sep 06,2020

Radar | May 06,2023

Radar | Sep 26,2021

Radar | May 07,2022

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 5 , 2025

Six years ago, Ethiopia was the darling of international liberal commentators. A year...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jun 14 , 2025

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars...