Fortune News | Oct 21,2023

Apr 13 , 2025

By Ahmed T. Abdulkadir

A country where over one third of its population is under the age of 30, Ethiopia faces a quiet crisis in education, threatening the future of millions. Schools, intended as places of growth, are increasingly becoming necropoleis of potential. Measures taken to address the crisis are paradoxically deepening it.

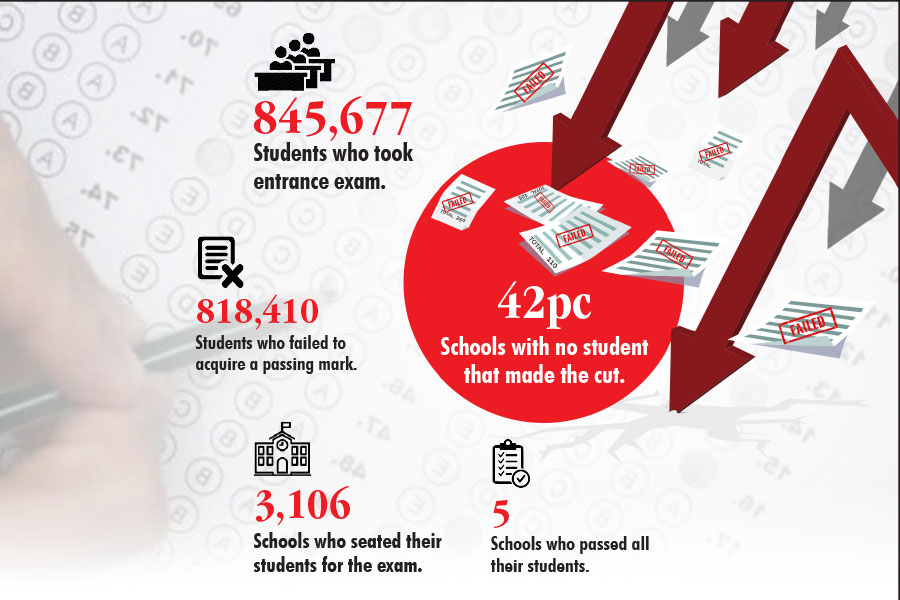

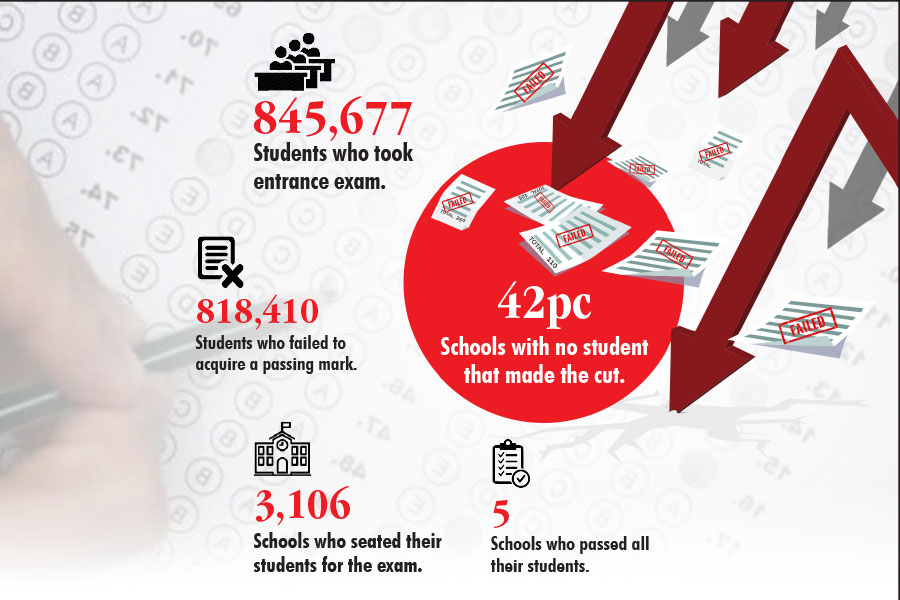

Calling the statistics alarming should be an understatement. Last year, over 684,000 students sat for the Grade 12 national examination. Only 5.4pc passed, leaving the rest to the harsh reality that their 12 years of schooling amounted to little. The previous year's results were even more dismal, with a mere 3.2pc passing rate. Shockingly, in over 1,300 schools countrywide, not a single student achieved a passing score.

These figures are not anomalies but should be taken as clear indicators of an education system in deep distress.

Education officials have attributed the declining pass rates to curriculum reforms and exam restructuring, yet the fundamental issues remain largely unaddressed. Chronic underfunding and neglect are to blame, especially in primary and secondary education. Although education comprises 10pc of the federal budget, almost half is directed towards tertiary institutions, benefiting only three percent of students. The remaining 60pc allocated to basic education, where foundational skills are supposed to be developed, is insufficient.

The imbalance leaves public schools severely overcrowded and lacking essential resources. Class sizes frequently range from 50 to 60 students per teacher. Textbooks are rare, science laboratories lie unused, and libraries, where they exist, often resemble neglected museums. Teachers frequently lack adequate training, aggravating an already dire situation.

Further complicating matters, the federal government recently eliminated the Grade 10 national exam. The abrupt shift forced students to transition directly from general education to advanced, university-track coursework without adequate preparation, making failure virtually inevitable. The absence of a proper bridge has widened gaps in learning, contributing further to the overall decline.

Political instability and violent conflicts in several regions have not helped the situation. They send approximately nine million children out of school entirely. Over 10,000 educational institutions across the country have been damaged or destroyed by ongoing violence, particularly in regional states like Tigray, Amhara, and Oromia. Many children in these areas have missed years of schooling, further weakening their educational foundation.

Ironically, the authorities' response often centres on slogans about modernisation, reform, and increased access without tangible action or sufficient investment. Genuine reform requires resources, well-trained teachers, secure classrooms, and evidence-based curricula rather than merely reshuffling personnel or delivering empty promises.

One of the latest initiatives proposed by the government is a national service program, slated for implementation in the 2026/2027 academic year. Under this plan, university students would spend a year teaching in underserved areas to respond to chronic teacher shortages and cultivate civic engagement. While well-intentioned, the strategy risks exacerbating existing problems by deploying inexperienced students into unstable regions, with poor infrastructure and overstretched budgets.

The initiative could do more harm than good, exposing students and communities to unnecessary risks. With tens of thousands of qualified teachers absent and many classrooms barely functional, placing untrained students in charge may further degrade educational quality. The extra mandatory year could disproportionately impact rural and economically disadvantaged students, making the dream of obtaining a university degree even more elusive and increasing dropout rates.

Instead of broad-based programs like national service, immediate and targeted interventions are required. These include emergency funding for repairing and rebuilding school infrastructure, comprehensive training programs for teachers, and dedicated mental health support for students repeatedly demoralised by systemic failures. Long-term strategic planning is equally essential. Budget priorities should shift towards basic education, which forms the foundation for later success. Curriculum changes could be guided by research and context-specific needs, not political considerations or donor demands.

The more accurate measure of the educational crisis is not found in examination results but in the daily experiences of students who travel hours to overcrowded classrooms, only to be told they have failed. It lies in the quiet desperation of teachers tasked with impossible expectations and inadequate resources. Most critically, it is shaped by every policy decision made at the intersection of crisis and meaningful reform.

PUBLISHED ON

Apr 13, 2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1302]

AhmedT. Abdulkadir (ahmedteyib.abdulkadir@addisfortune.net) is the Editor-in-Chief at Addis Fortune. With a critical eye on class dynamics, public policy, and the cultural undercurrents shaping Ethiopian society.

Fortune News | Oct 21,2023

Commentaries | Mar 18,2023

Viewpoints | Oct 12,2024

Covid-19 | Apr 25,2020

Viewpoints | May 11,2024

Fortune News | Dec 30,2023

Fortune News | Jan 09,2021

Commentaries | Jul 18,2020

Fortune News | May 06,2023

My Opinion | 131981 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 128369 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 126307 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123925 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 5 , 2025

Six years ago, Ethiopia was the darling of international liberal commentators. A year...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jun 14 , 2025

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal legislature gave Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) what he wanted: a 1.9 tr...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

In a city rising skyward at breakneck speed, a reckoning has arrived. Authorities in...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A landmark directive from the Ministry of Finance signals a paradigm shift in the cou...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Awash Bank has announced plans to establish a dedicated investment banking subsidiary...