Sep 18 , 2021.

It could be customary to wish well for the holiday seasons. If only the New Year celebrated in Ethiopia last week had a consistent theme.

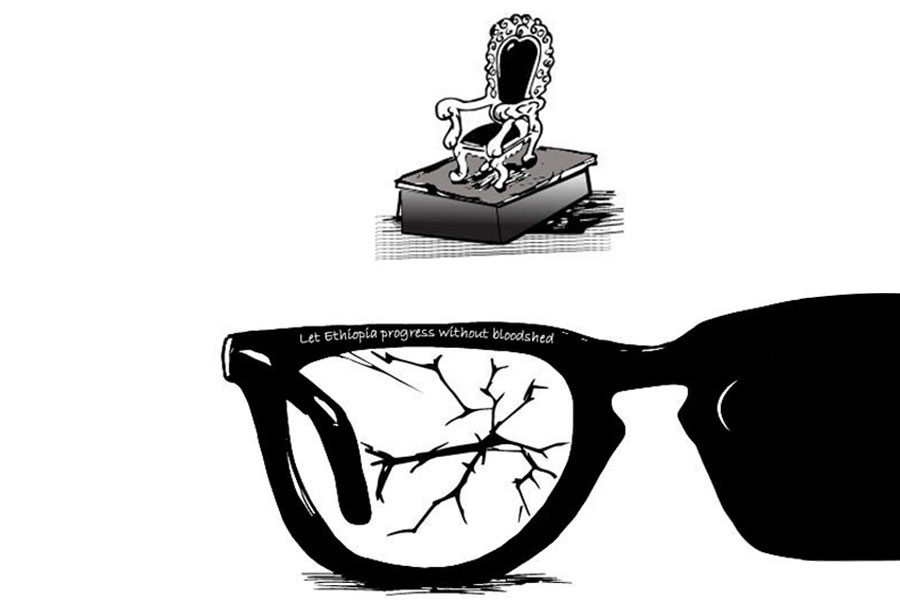

Nonetheless, many had gone into their social media pages wishing the New Year - 2014 - to be one where the guns are silenced, and peace is restored. This should not be surprising for a country that finds itself on its knees due to political instability and civil war. But for a society that has long romanticised war and where nationalism informs much of the political discourse, this could be seen as refreshing.

If there is a silver lining to the horrors of wars, how deeply they cinch the terrible and traumatising experience of going through it in memory is one. It partly explains why countries with a history of militarism, such as Germany and Japan, eventually developed an aversion for violence in their politics. Take Otto von Bismarck, the German statesman. He mostly wore an army General’s uniform despite no significant career in the military, compared to present-day Germany of anti-militarism politics.

The difference for countries such as Ethiopia is that the experience of suffering in the past has not been sufficiently internalised and utilised as momentum to find a political settlement anchored on peace and development. This is the freedom from “want and fear”. But without such a settlement, fear (insecurity) and want (extreme poverty) have unleashed a vicious cycle that claims lives and livelihoods.

If the modest calls for peace that are heard now more loudly than when the latest civil war began last November are cognizant of this, then a pacifist movement in the offing needs to be encouraged. But this is unlikely to be the case. There is no defined structure or even influential groups lending unrelenting support for pacifism, as the United Nations Charter espouses it, to gain ground. The UN Charter, in its Article Six, urges "warring parties to resolve differences via mechanisms such as mediation."

States have a reputational disadvantage to avoid in the face of the international community and perhaps the desire to use mediation as a stalling tactic in raging civil wars. For the rebellious groups that challenge the state, the quest for legitimacy is a significant incentive for them to come to the table of mediation. Provided that there is sufficient interest by the international community to commit time and resources, mediation of the warring parties in Ethiopia is not only desirable. It is possible.

According to a study by Tanisha M. Fazal, a professor of Political Science at the University of Minnesota and author of the acclaimed book "Wars of Law", civil wars with mediation are more than six times more likely to end in peace deals than unmediated one's.

There appears to be war-weariness creeping among a few quarters of the urban elite. It should be a welcome development for an anti-war coalition (not yet a social movement for pacifism) to form, born out of the recognition of how long and how much bloodier the war can get. Battles fought along the fault lines of ideology, territory or economic resources are devastating. However, the dilemma of Ethiopia is much more complex. The lines are drawn along identities and authority. It is a battle over culture, history and power. No one is allowed to sit it out or claim neutrality; not even children are spared.

There seems no end in sight unless one side prevails, vanquishing the other, which would only be a lull until the next war begins. It is a zero-sum game engagement that aspires for peace in captivity. In the absence of negotiated settlement, the peace that comes is a "victorious peace", dictated and imposed by the party that claims victory.

It should not be the case because there are alternatives. The history of the world since World War II, particularly with the end of the Cold War, shows civil wars were concluded in negotiated settlement and peace deals. More than half of civil wars in the 20 years beginning in 1989 were ended in peace treaties, compared to 11pc of the civil wars held in the world in the 175 years before 1989. More civil wars today end via negotiated settlements than did prior to 1945, according to Professor Fazal.

It is good to see voices terrified of the consequences of war are beginning to be heard, as belated as they have been to emerge. Suffice the petition signed by over 20 members of the civil society a couple of weeks ago, calling for the peaceful resolutions of the ongoing conflict in Ethiopia.

This and similar initiatives urging for peace are highly atomised, though. There are individual voices in media, academia and even politics making a case for it here and there; a few firms messaging it as part of corporate social activism (including a bold commercial from BGI Ethiopia over the holiday); and a spattering of non-profits trying to create platforms for dialogue (having in mind the efforts of the MIND).

These calls may have come from the realisation that the road ahead could be long and daunting, but not in any way worse than a war that promises the perpetuation of conflicts and poverty for generations to come. But before an anti-war movement can help swing the public discourse in favour of negotiated settlement instead of military engagements, consolidation is essential. The war camp has built steel and concrete fortifications against any possibility of compromise; throwing a few scattered voices against such a barrier hardly makes a dent.

The fractured voices calling for the peaceful resolutions of the militarized conflicts have little chance of breaking through the war camp's fortifications within the political space. Once a country is in a state of war, the momentum is with the hawks. The possibility of groups ever tolerating one another becomes a distant memory and an anomaly to the political imagination. Those who hold the state power and their hawkish supporters are unwilling to come to the negotiating table because they fear the very appearance gives their "rebel adversaries" legitimacy. The latter avoid talks for a negotiated settlement, for they realise in the end they will be compelled to disarm, leading to what Professor Fazal describes as a "commitment problem."

How to overcome the duality of the issue between legitimacy trap and commitment problem remains a formidable challenge for initiatives and efforts to bring Ethiopia back to the peace trajectory. But in the absence of bottom-up pressure from a pacifist movement, not much can be done by these fractured voices alone.

No less pertinent is for the pacifist camp to emerge on all the political aisles, not only on opposite sides of the battlefront. An anti-war effort that calls for a ceasefire but stays silent on humanitarian and human rights fronts cannot become credible either. Relationships between groups of opposing political persuasions need to be nurtured. Without inclusivity, such a movement will find it difficult to get the attention from every side - this is bad because all sides need to be committed to peace, not unilaterally.

Neither can initiatives for non-violent engagements grow unless there are diverse voices that allow the anti-war movement to grow in its philosophical and political potency. They may not need to consolidate into a single structure, but there is a dire need for them to piggyback off one another. What they should consolidate is their voices, resources and know-how to make their cause ring louder. Unless they constantly support one another’s initiatives, their lobbying would remain muffled by the deafening noise of the war camp, which has overwhelmed the media space and the public domain.

The only price of admission to join and consolidate the pacifist movement should be a call for a settlement of all political issues through dialogue and not armed conflict. As long as the central message is the protection of lives and livelihoods of citizens and for the guns to be silenced, such voices are playing for the same team. They can play the cards right in pressuring for a negotiated settlement of differences, however insurmountable they may appear.

The monumental contribution of the domestic coalition for peace could be putting enough pressure for this mediation to happen. And the first significant test for anti-war initiatives is to show commitment to the greater good: the absence of violent conflicts. If they cannot do this, they should not expect those on the battlefront to be any better.

PUBLISHED ON

Sep 18,2021 [ VOL

22 , NO

1116]

Editorial | Nov 11,2023

Editorial | Dec 19,2020

Fortune News | Apr 30,2022

Fortune News | Nov 18,2023

Fortune News | Jan 07,2022

Radar | Feb 27,2021

Advertorials | Apr 10,2023

Sponsored Contents | Oct 25,2021

Radar | Oct 16,2021

Editorial | Jul 17,2022

My Opinion | 131987 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 128376 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 126313 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123931 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

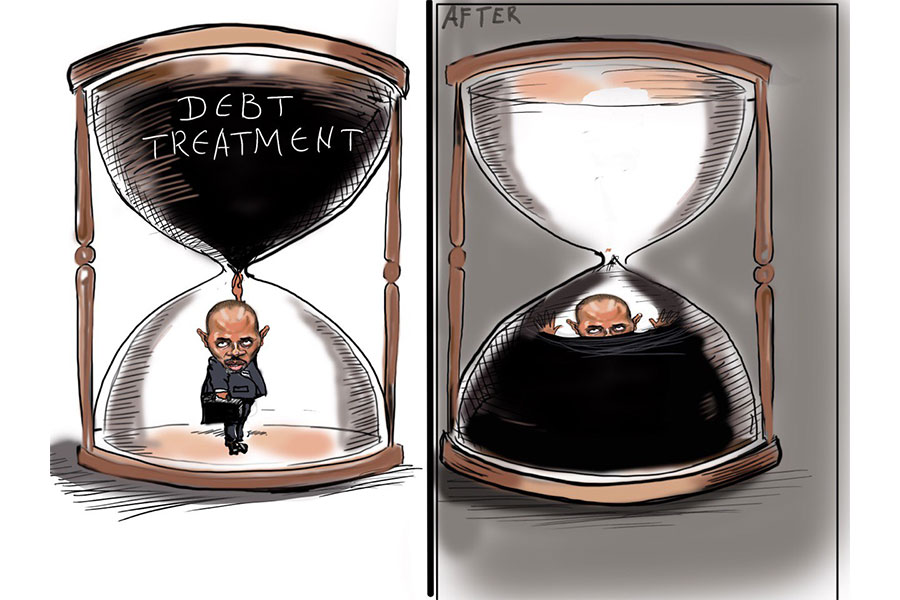

The federal legislature gave Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) what he wanted: a 1.9 tr...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

In a city rising skyward at breakneck speed, a reckoning has arrived. Authorities in...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A landmark directive from the Ministry of Finance signals a paradigm shift in the cou...

Jul 6 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Awash Bank has announced plans to establish a dedicated investment banking subsidiary...