Agenda | Sep 28,2019

Jul 13 , 2020.

Last week might have appeared an ordinary moment for an annual event in parliament. Legislators voted - unanimously - over a bill for the next fiscal year’s budget for the federal government. They read questions they had sent through a week earlier, raising a number of much discussed grievances, from the security situation in the country to public health challenges in light of the Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. As expected, the trials the economy is facing took much of the session, which unusually extended to four hours.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) addressed these questions, matching the lack of sense of urgency the legislators had displayed. There would undoubtedly be challenges he sees. But nothing insurmountable. The general trajectory of the national economy would be one of sustained rapid growth, he told legislators.

His ministers and macroeconomic planners were no less complacent in the face of the despair of winter in both the global and domestic economies. They have produced a federal budget based on assumptions that are far from prudent.

Such lack of prudence in planning was apparent in the tone of the parliamentary session last week. It failed to recognise that Ethiopia’s economy has been and continue to be profoundly challenged by the twin trends of a global recession and domestic political instability.

These are headaches that are unlikely to be addressed by throwing money at the problem. It is hard to imagine the administration paying its way out of the dilemma between facing stagflation and the skyrocketing cost of living. Injecting more money into the economy may be what complicates matters further, which was what parliamentarians voted to do last Tuesday, July 7, 2020.

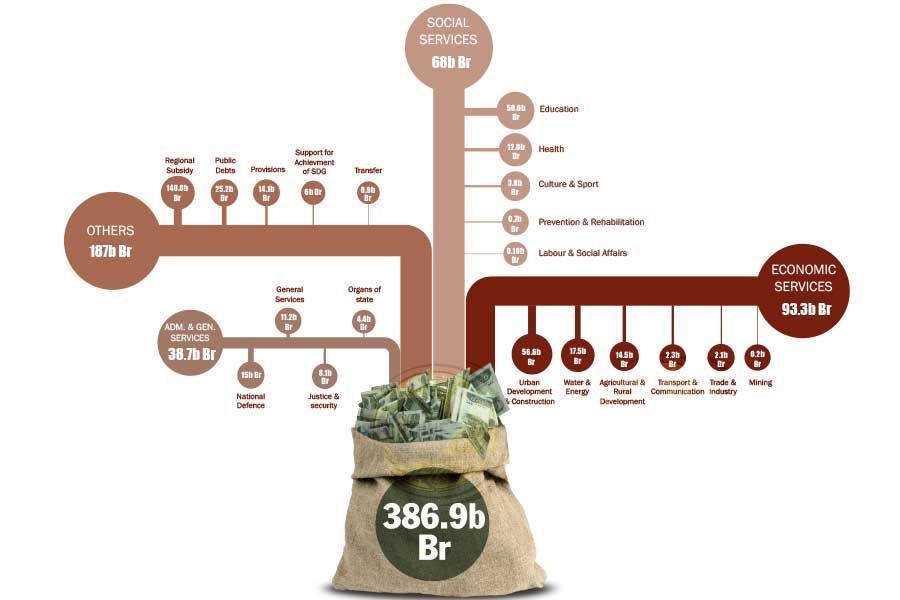

The bill that was passed by parliament does exactly that. At 476 billion Br, it was not only the largest budget the federal government had ever worked with. It also showed one of the highest year-on-year jumps that has ever been seen. In aggregate, it is 83 billion Br higher than the previous fiscal year’s budget. It represents an amount comprising the entire public expenditure for the year 2002.

The justifications for this are understandable, nonetheless.

With double digit inflation chugging along at a worrying year-on-year average of about 19pc, coupled with a fast depreciating Birr, this meant that there was actually a two percent increase to the federal budget in dollar terms. A budget of this size might sound like a rational and sensible increase to public expenditure. In the economics parlance, it is known as "inflationary financing."

This may appear a U-turn from the much touted economic reform programmes the administration wants to carry out by rebalancing the macroeconomy and introducing a tight monetary policy and fiscal stance. Reality dictates that inflationary pressure in the economy and significantly reduced economic growth will only lead to massive unemployment. The rationale that the government has to jump-start the economy and thus needs an expansive budget could be a digestable idea.

But such scenario works where there is a domestic productive capacity that can meet an aggregate demand by an expansive fiscal position.

Neither is it clear how the administration plans to pay for a budget ballooning, at least in Birr terms, in any other way than printing money. The projected tax revenues for the next fiscal year, 272 billion Br, is expected to cover 64pc of the federal budget. It is far higher, by about a third, than what the government managed to collect in the previous fiscal year.

Macroeconomic planners should have little reason to believe this amount can be collected in full. The record from the recently ended fiscal year showed that only 82pc of the planned 244.8 billion Br in domestic revenues were collected, declining by 10pc from the previous year. The trend since the year 2005 shows nothing different: tax revenues growing by an average of 19.3pc.

But the sheer number of challenges working against the economy are unprecedented, even considering the depressed growth of the past fiscal year, to justify such an assessment the Minister of Finance, Ahmed Shide, and his team have come to hold.

With global supply chains and logistics still reeling from the impact of the global COVID-19 pandemic, manufacturers who depend on the import of raw materials have been affected negatively. Perhaps more worryingly, remittances to Ethiopia and the tourism industry are in dire straits, likely to substantially affect dwindling foreign currency reserves. The former is expected to fall by 23pc across sub-Saharan Africa in 2020, according to the World Bank. The latter, which brings to Ethiopia’s economy well over two billion dollars annually, is bound to create a gaping hole in foreign currency reserves as international tourist arrivals are expected to drop substantially.

These are just the challenges from COVID-19 alone, which by the government’s estimate has impacted growth by two to three percent. The international financial institutions have a bleak outlook. They find it hard to foresee GDP growing by more than 3.2pc, a monumental loss compared to the impressive growth trajectory Ethiopia witnessed over the previous 15 years.

Ethiopia is likely to enter a time of even greater political volatility in the coming year by virtue of the profound constitutional issues following the indefinite postponement of the national elections. The consequences of this will be felt severely in an ever lower appetite for domestic investments. Flows in foreign direct investment (FDI) may be buttressed as a result of lower interest rates in much of the developed world. But it is hard to see how investors

can see past all the political uncertainties to risk pouring money into the national economy with the hope of generating profits.

These unprecedented challenges to the economy should have put a greater sense of urgency in the eyes of parliamentarians, the Prime Minister and his economic advisors, such as Girma Birru, to raise sensible questions.

It is a no-brainer to see that the economy will be hard pressed to expand by 8.5pc; that inflation is unlikely to be kept at bay at nine percent; and domestic resource mobilisation will be an uphill task to reach anywhere close to the amount that is planned. Neither will the deep recession in the global economy, projected to last as long as 2022, allow 4.5pc growth in the value of goods the administration foresees.

Granted, the export of goods had shown a slight improvement, which is not saying much considering the level of stagnation over the past half decade. This is reflected in the revenues from exports, which could cover 17.3pc of imports in 2019 compared to 34.3pc in 2011.

Depressed economic growth, if not contraction, puts into question the tax revenues the government plans to collect in the next fiscal year, which the Finance Minister himself has acknowledged is “overambitious.” Indeed, covering much of the federal budget through tax revenues will leave a fiscal deficit at three percent of GDP, forcing the government to borrow close to 78 billion Br from domestic sources.

But a testament to the nearly unfathomable challenges this country faces in its near future, an expansionary budget of the sort that was approved by parliament may actually be the better of two evils.

Shortly after the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic began to bite, Prime Minister Abiy's administration had rightly broadened the fiscal space, hoping to support economic sectors that would be severely impacted. There have been tax waivers and debt remittances, and funds have been made available for banks to provide payroll protection in the hospitality industry.

The call from the business community and pundits has in fact been for the government to risk inflation in the name of stimulating economic activities through a higher fiscal deficit. Inflation had been rising anyway, mostly because Ethiopia is an import-dependent country. The logical step seemed to be not to compound this with unemployment as businesses fail and investment slumps.

An expansionary budget for a fiscal year that will most likely see depressed economic activities was thus the understandable Keynesian response to increase aggregate demand, stave off business failure and combat unemployment.

However, macroeconomic policymakers should be in no doubt that the country has entered an economic winter, and thawing it will require a sense of urgency much more noticeable than the sort the Prime Minister and his economic advisors seemed to have shown. As the government fails to collect its “overambitious” revenues from taxes in an economy severely impacted by a pandemic and political uncertainty, it will have to print the notes. Brace for a low growth and highly inflationary macroeconomic reality that will not be served any better by a raging virus and combustible political instability.

PUBLISHED ON

Jul 13,2020 [ VOL

21 , NO

1055]

Agenda | Sep 28,2019

Radar | Aug 10,2025

Sunday with Eden | Oct 22,2022

Radar | Jan 15,2022

Radar | Jun 07,2025

Agenda | Aug 10,2025

My Opinion | Jun 14,2025

Fortune News | May 11,2019

Fortune News | Jul 13,2019

View From Arada | Nov 05,2022

Photo Gallery | 178207 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 168414 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 159186 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 137055 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 25 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

Officials of the Addis Abeba's Education Bureau have embarked on an ambitious experim...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The federal government is making a landmark shift in its investment incentive regime...

Oct 29 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) is preparing to issue a directive that will funda...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A community of booksellers shadowing the Ethiopian National Theatre has been jolted b...