View From Arada | Apr 30,2021

Sep 28 , 2019

By Clay Webster

Clay Webster studied energy and environmental policy at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. He has written about energy, commodity and financial markets for The Motley Fool, Plattsand US News & World Report.

One of the weaknesses of modern democracies is their dependence on the immediate whims of voters. With much of the electorate focused on temporary zeitgeists or simplistic negative partisanship, the achievements or popularity of the current government is too often confused with that of the state as a whole.

If an elected leader performs poorly, the average voter often condemns the whole system itself and paints the entire state apparatus as necessarily rigged. The problem is that in any democracy, a large minority of voters tends to be disgruntled with the current leadership at any given time. With our current age of 24-hour news shows, minute-by-minute updates and political posturing on social media, the fallibility of political leaders, unfortunately, becomes apparent to even the casual observer.

With this as a backdrop, it is hard not to occasionally look back, with somewhat too nostalgic memories of course, at our pre-democratic age. In the past, very few of us controlled the nature of the states in which we lived. But it must have been at least somewhat reassuring to live in a society with a continuity attached to it – the knowledge that the state had existed before one’s birth and would likely carry on past one’s death.

Of course, many Ethiopians alive today remember living under a monarchy and may still retain this sense of awe. In this time of political uncertainty, even many of the youth hold up 19th-century monarchs as ideal leaders.

But many visitors find it curious in the present day United States that an electorate who has only known democratic governance for the last 230 years still reveres its “founding fathers” as the pinnacle of national leadership, a category that suffers clear comparisons to the semi-divine respect given to actual royalty. Of course, the fact that many of them were self-conscious slave traders and thought only white men who owned land should be given the vote is brushed aside. There is something primordial in our contemporary democratic psyches, in which the current stock of meritorious elites is never quite deemed worthy of polishing the shoes of those distant monarchs.

It is hard to feel that Ethiopia gained some level of sophistication by jettisoning its monarchy, following in the footsteps of many recently liberated African nations of the time and the “modern,” anti-historical Americans.

My question is this. What would it look like if the country reintroduced the Solomonic Dynasty as a symbolic, constitutional monarchy with zero political power?

Before shruging off this impossibility, consider the state of many advanced democracies around the world. Rather than splicing their history in half with a monarchical past and a democratic future, they have opted for hybrid designations. Denmark and the United Kingdom both have constitutional monarchies headed by queens. Thailand has a king. Japan has an emperor.

What these mostly symbolic leaders all have in common is that they serve as a focal point to uplift the hearts and minds of their countrymen. When King Bhumibol of Thailand passed away in 2016 after 70 years on the throne, thousands of Thais slept in the streets to reserve places to observe his funeral procession. The King had remained on the throne through more than 20 prime ministers and many coups, a disruptive democratic adolescence to say the least. But through all those crises, Thais had a sense of continuity, as their symbolic leader remained in place, stoically reassuring them that the state would carry on.

The other advantage that cannot be ignored about these constitutional monarchies is that they bring in significant amounts of tourism. As a nation that both requires all the foreign currency it can muster for economic development and loan repayment, the reinstating of a symbolic monarchy could be a significant game-changer.

Having a monarchy presents a nation with a certain cachet, a certain prestige that attracts a high-paying clientele, who often visit other sites and stay at hotels. When Prince Harry and Meghan Markle got married, the royal wedding brought in an estimated 1.4 billion dollars to the UK economy. When tourists flock to see the royals in an average year, the UK brings in more than 550 million British pounds. That’s a lot of foreign currency. In many ways, royal tourism is its own economic sector.

With Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) already undertaking significant renovations at the National Palace, what could make the future “museum” better than having a live royal couple living in the royal abode?

Imagine the thrill of attending a bunaceremony with the King and Queen.

What royalty does for a people is demonstrate that they are not just the inheritors of a modern democracy, which while respecting the wishes of its electorate often must descend into the petty squabbling inherent in its structure. What royalty signifies is that a citizen is not just an atomised cog in the broader electorate but also a descendant of a rich history much bigger than oneself, of a people deserving of kings and queens.

Yekuno Amlak’s leg of the Solomonic Dynasty, for all its issues and defects, ruled unbroken through prosperity and eras of decline for more than 700 years. King Bhumibol’s Chakri Dynasty is less than 240 years old. The current House of Windsor that presides in the UK is barely more than 100 years old. In light of 700 years, the last 45 seem like a mistake.

PUBLISHED ON

Sep 28,2019 [ VOL

20 , NO

1013]

View From Arada | Apr 30,2021

Fortune News | Jan 07,2022

My Opinion | Aug 01,2020

Radar | Jul 20,2019

Radar | Jul 18,2020

Radar | Jan 25,2020

Radar | Jul 02,2022

Radar | Jan 25,2020

Fortune News | Jan 18,2020

Radar | Jun 01,2019

Photo Gallery | 154127 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 144379 Views | Apr 26,2019

My Opinion | 134920 Views | Aug 14,2021

Photo Gallery | 132652 Views | Oct 06,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Sep 6 , 2025

The dawn of a new year is more than a simple turning of the calendar. It is a moment...

Aug 30 , 2025

For Germans, Otto von Bismarck is first remembered as the architect of a unified nati...

Aug 23 , 2025

Banks have a new obsession. After decades chasing deposits and, more recently, digita...

Aug 16 , 2025

A decade ago, a case in the United States (US) jolted Wall Street. An ambulance opera...

Sep 7 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

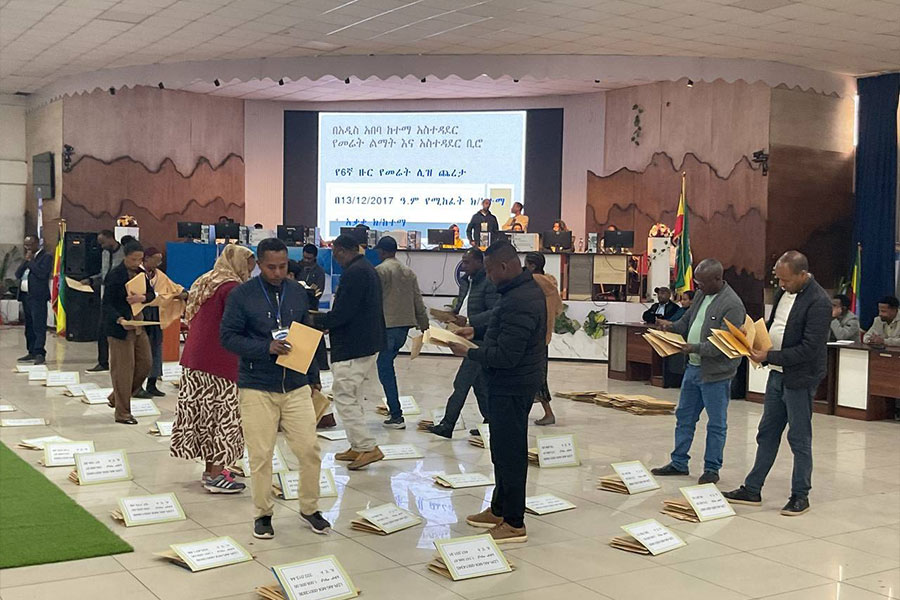

Addis Abeba's sixth public land lease auctions after a five-year pause delivered mixe...

Sep 7 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Brook Taye (PhD), the chief executive of the Ethiopian Investment Holdings (EIH), is...

Sep 7 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

For decades, Shemiz Tera in the Addis Ketema District of Atena tera has been a thrivi...

Sep 7 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A dream of affordable homeownership has dissolved into a courtroom showdown for hundr...