Viewpoints | May 01,2020

Sep 7 , 2019

By Ahadu Y. Assefa

Despite the concerns, it is difficult to brand the BRI as a debt trap. However, there is a need for transparency in this initiative, as greater transparency would also help address additional concerns and will deflect at least some criticism forwarded against the initiative, writes Ahadu Y. Assefa , an LLM student at Greenwich University in London.

An estimated 5,000 foreign officials and business delegates from 36 countries were in Beijing attending the two-day Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) forum in April 2019. Guests included President Vladimir Putin of Russia and ex-Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte of Italy, the first G7 country to endorse Chinese president Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy. Prime Minister, Abiy Ahmed (PhD), was also in attendance.

Leading up to this forum, however, Western governments became increasingly wary of China's growing influence. The US has been particularly critical of the BRI. Vice President Mike Pence and US National Security Adviser John Bolton said on different occasions that China was using "debt diplomacy" to expand its influence around the world. And the Chinese government, in the April 2019 forum, found itself defending the BRI by convincing the international community that the initiative is inclusive and making policy concessions in areas including debt sustainability. But how did it get here?

President Xi of China announced the BRI during official visits to Kazakhstan and Indonesia in 2013. The BRI is an ambitious programme to connect Asia with Africa and Europe via land and maritime networks along six corridors to improve regional integration, increasing trade and stimulating economic growth with the total investment predicted to be over 8 trillion dollars.

The plan was two-pronged: the overland Silk Road Economic Belt stretching from China to Europe and the Maritime Silk Road. The two were collectively referred to first as the One Belt, One Road initiative but eventually became the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). As a conscious and deliberate move, the BRI shows a more overtly activist Chinese policy in the world at large. This approach shifts away in principle from Xi’s predecessors who followed the maxim: “Hide your strength, bide your time, never take the lead.”

China has both geopolitical and economic motivations behind the initiative. Put simply, President Xi has promoted a vision of a more assertive China, while the new normal of slowing growth has put pressure on the country’s leadership to open new markets for its consumer goods and excess industrial capacity. This oversupply in the domestic market of China needs a new demand to keep it moving forward.

But there have been growing concerns over the intentions of China and the financing of some projects that brands the initiative with criticism. Some writers refer to the BRI as “an overt expression of China’s power ambitions in the 21st century,” arguing that Beijing’s goal is to reshape the global geopolitical balance of power. Others frame it in less adversarial terms, saying the Chinese leadership “simply hopes the BRI will improve China’s image among its neighbours, and help to rejuvenate them economically.”

Given its grand ambition, the BRI, as one writer puts it, "is [the] best-known, least-understood foreign policy effort underway, with little reliable information about how it is unfolding overall." The IMF has reported that the lack of transparency in China’s lending obscures its risks to recipient countries, many of which are already vulnerable to or are suffering from financial or fiscal distress.

And lack of transparency in procurement and project awarding coupled with lack of economic feasibility of some BRI projects, many observers suspect that the initiative is partly motivated by China’s desire to stimulate its own economy, obtain strategic assets, and convert its economic access into political and strategic influence in recipient nations.

This has led to "hidden debt" and "debt trap" accusations forwarded mostly by the Western world, as the Chinese effort is said to stand outside of international efforts - principally driven through the IMF and World Bank - to promote transparency, which improves policy making, prevents debt crises and discourages corruption.

The case that fueled this accusation was the takeover of a Sri Lankan port. A Chinese state-controlled company, China Merchants Port Holdings, took over operation of Sri Lanka’s 1.3-billion-dollar Hambantota Port on a 99-year lease after that country defaulted on loan payments. According to a document released by Wikileaks, the first major loan for the project for 307 million was given on the condition that Sri Lanka was required to accept Beijing’s preferred company, China Harbour, as the port’s builder. This has become a trend for projects under the BRI to be built by Chinese companies and labourers.

Critics have raised concern that this hand over might set a precedent for other countries that owe money to China to accept deals that involve the signing over of territory. This concern is present in Africa and, more specifically, the Horn of Africa. There was a leaked report from Wikileaks stating that Kenya might be forced to handover the Mombasa port to the same Chinese company that took over the Sri Lankan port if it defaults on the loan for the construction of the giant Mombasa-Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway project. This report showed that President Uhuru Kenyatta had in 2013 waived the Mombasa Port's sovereign immunity to use it as a security for the Chinese loan. Although it had not materialised, it still lingers as a fear in Kenya.

The main concern is for Djibouti. As the Institute for Securities Studies (ISS) puts it, Djibouti is at the core of BRI as an important trade corridor. China has taken root in Djibouti through numerous infrastructure projects including a new port, two new airports and the Ethiopia-Djibouti Railway. The sheer scale of these projects, combined with the fact that they are concentrated in a small but strategically located, cash-strapped country, make China’s presence significant. According to a Centre for Global Development report, Djibouti’s public debt is around 88pc of the country’s GDP, with China owning the lion’s share of it. The IMF has also warned that Djibouti’s debt is not sustainable at this rate. Djibouti is also home to China’s first overseas military base. All these factors raise concern that Djibouti may be forced to hand over important assets to China.

Information inconsistencies are also seen in BRI projects. The Ethio-Djibouti Railway project is a good example. This project was financed by the Ethiopian government and by a loan from China’s Exim Bank. Chinese media reported that Exim Bank provided 85pc of the funding. Whereas, Ethiopian media reported that only 70pc of the financing was from Exim Bank. Details are also not quite clear about the total cost of construction, which reached 4.5 billion dollars, at least half a billion more than originally planned. Reutersreported the cost at 4 billion dollars. These inconsistencies may not be severe, but it shows how BRI projects do not have consistent information, leaving room for speculation from various parties on the motive and success of these projects.

Despite the concerns, it is difficult to brand the initiative as a debt trap. The only case that has been a concern is the Sri Lankan port. This is only one project, and the BRI does contain numerous projects.

A senior advisor for Asia at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies says the debt trap critique is unfounded. At the end of the day, the Chinese banks want to be repaid. But the advisor said it might reflect China’s views on a country’s right to make its own decisions – "A Chinese view is, ‘Well, that’s not our responsibility. It’s their responsibility.’"

But the common theme from the concerns and the above country cases is the lack of transparency on the projects. And there is a need for transparency in this initiative. Transparency is needed throughout the project life, including information disclosure relating to project financing, siting, tendering, procurement processes, anticipated fiscal, environmental, social and other impacts, project contracts and project implementation. This should not affect confidential information on the project that is expected to remain confidential.

Transparency also prevents debt crises. Organisations, mainly the IMF, whose main purpose is to stabilise the world economy, need information to perform their duty. This means that if the IMF is doing debt sustainability on Djibouti, unless they know how much Djibouti owes China, they are doing that sustainability exercise blindfolded. It also discourages corruption by making firms aware of opportunities, to contest procurement decisions and assure there is accountability and integrity.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in one study concluded that well-executed consultation processes in infrastructure projects could enhance the legitimacy of the project within the community and foster a sense of shared ownership. This is important to local communities and citizens who will be directly affected by the projects.

Greater transparency regarding BRI projects and their implementation would also help address additional concerns regarding the environmental and social sustainability of BRI projects - which again directly implicates local populations. And finally, it will erode at least some criticism forwarded against the initiative.

PUBLISHED ON

Sep 07,2019 [ VOL

20 , NO

1010]

Viewpoints | May 01,2020

Advertorials | May 30,2025

Fortune News | Aug 16,2020

My Opinion | Jun 17,2023

Fortune News | Dec 08,2024

Radar | Aug 21,2021

Advertorials | Jul 08,2024

Radar | Jul 27,2025

Life Matters | Apr 03,2021

Radar | Nov 27,2021

Photo Gallery | 156506 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 146793 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 135324 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 135246 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Sep 13 , 2025

At its launch in Nairobi two years ago, the Africa Climate Summit was billed as the f...

Sep 6 , 2025

The dawn of a new year is more than a simple turning of the calendar. It is a moment...

Aug 30 , 2025

For Germans, Otto von Bismarck is first remembered as the architect of a unified nati...

Aug 23 , 2025

Banks have a new obsession. After decades chasing deposits and, more recently, digita...

Sep 15 , 2025 . By AMANUEL BEKELE

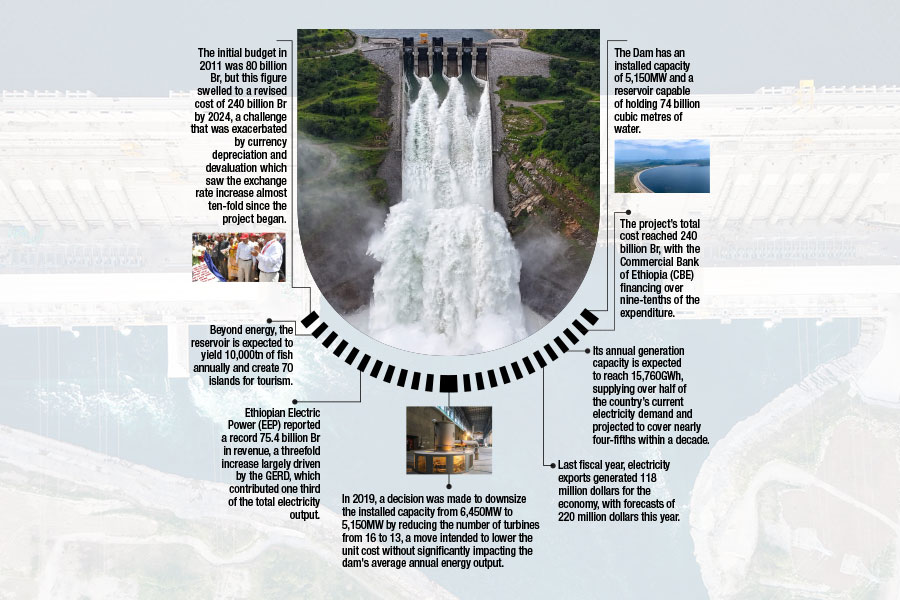

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), Africa's largest hydroelectric power proj...

Sep 13 , 2025

The initial budget in 2011 was 80 billion Br, but this figure swelled to a revised cost of 240 billion Br by 2024, a challenge that was exac...

Banks are facing growing pressure to make sustainability central to their operations as regulators and in...

Sep 15 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The Addis Abeba City Cabinet has enacted a landmark reform to its long-contentious setback regulations, a...