Jan 25 , 2025

By Frederic G. Ngoga (Amb.)

Last year, the African Union’s Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace & Security, Bankole Adeoye (Amb.), described a growing phenomenon that could determine the fate of many African countries. He stated the rise of artificial intelligence's (AI) power to transform nearly every aspect of life, from governance to human security. But, he also warned that Africa risked becoming a testing ground for technologies that, while offering critical advantages, could introduce new threats if not properly regulated. He urged leaders to recognise AI’s dual potential, its promise to strengthen governance and peace, and its capacity to undermine both if left unchecked.

The concerns presented by Adeoye gained urgency as AI-driven tools began appearing in African conflict zones and security operations. Many saw the benefit of advanced surveillance systems, data-driven conflict prevention, and sophisticated early-warning mechanisms meant to help communities avert violence. In theory, AI could feed into the African Union’s Continental Early Warning System, offering richer, real-time intelligence on belligerents, the interplay of local actors, and hotspots where conflict might escalate.

The data these systems generate could, at least in part, support efforts to mediate disputes and encourage dialogue among communities teetering on the edge of conflict. AI could also be channelled into peacekeeping operations, making it easier to monitor ceasefires, broker peace agreements, and ensure that belligerents did not violate the terms of any negotiated settlement.

But, reality on the ground often brings a harsher perspective.

Over the last two years, African conflict theatres have seen more sophisticated deployment of AI tools than ever before. Using drones and autonomous systems has reshaped the balance of power and raised the stakes for state and non-state actors, many of whom do not follow international law. In places such as Libya, the Sahel, Sudan, Somalia, and the Great Lakes region, drones have been used for intelligence gathering, reconnaissance, and direct attacks on military installations and populated areas. This escalation has led to an alarming increase in civilian casualties, generating questions about the legal, ethical, and humanitarian consequences of AI-aided warfare.

In July 2024, reports of parties jamming global positioning systems and conducting spoofing cyberattacks sent jitters through security circles, stoking fears that these tactics could extend to civilian aviation and other critical infrastructure.

These developments have also troubled intelligence services, which are now struggling with evidence that terrorist organisations operating in the Sahel, as well as militant groups like Al Shabaab or the Islamic State in Somalia, have acquired and deployed drones against military camps. Ethiopia’s Air Force, presumably recognising this shift in the tactical environment, announced last year the establishment of a drone unit that would incorporate AI-driven capabilities. Such moves demonstrated a regional arms race in which AI becomes not merely an appendage to traditional military hardware but a decisive factor in how power is projected and maintained.

Beyond the visible use of AI in combat, there is a quieter threat with equally profound implications. Though ostensibly neutral, AI systems can become vectors of disinformation if hijacked or manipulated. A policy brief by the United Nations University Centre for Policy Research (UNU-CPR) discovered how generative AI, from natural language models to deepfake technologies, has accelerated the production and spread of false or misleading information. Since OpenAI’s ChatGPT was publicly launched in December 2022, political conflicts across sub-Saharan Africa have been inflamed by waves of AI-generated content crafted to mislead voters, promote extremist ideologies, or foment distrust in state institutions.

These toxic messages can now spread more rapidly and easily penetrate regions with limited internet access through proxies that exploit social media loopholes and local communication channels.

Complicating matters further, AI systems often draw on datasets that may embed ethnic, social, or economic biases. If a government or an institution invests in AI models without carefully auditing how they learn, it risks magnifying existing discrimination. In Africa, where fractures along tribal, religious, and socioeconomic lines can be acute, the deployment of biased AI could erode citizens’ trust in everything from law enforcement to judicial proceedings and inadvertently target vulnerable communities.

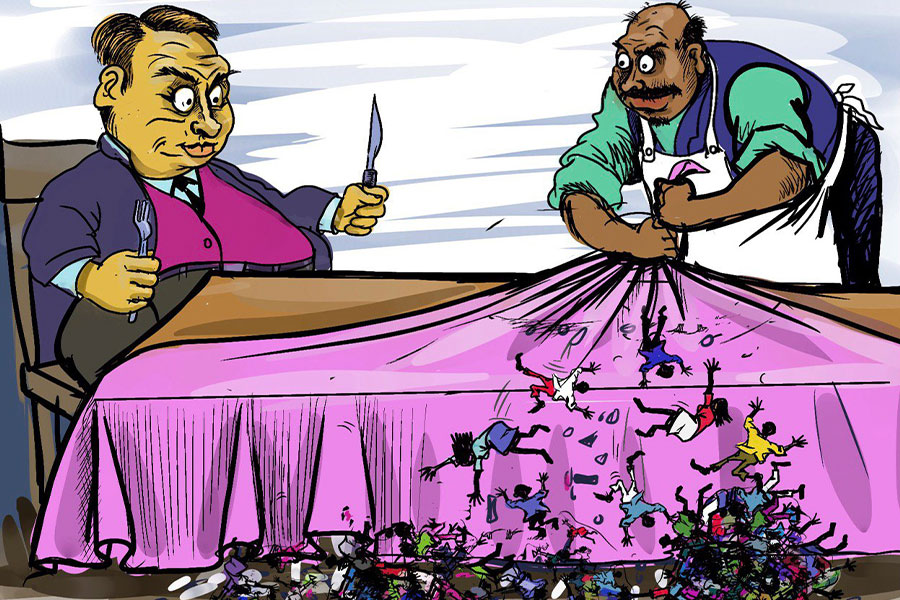

On the other side of the spectrum, authoritarian regimes could co-opt AI-driven surveillance tools to suppress political opposition, muzzle free speech, and cement their hold on power, all in the name of maintaining stability.

In response, the African Union Peace & Security Council (AUPSC) took several steps to guide AI's responsible integration into security policies. Its meeting, held on June 13, 2024, culminated in a communique that stressed the role of the African Union Commission in undertaking a comprehensive study on AI’s impact on peace, security, stability, democracy, and development. The document also recommended mainstreaming AI into peace processes, urging stakeholders to incorporate AI in mediation, reconciliation, and post-conflict reconstruction efforts. It offered guidance on integrating AI into military operations while complying with ethical standards and international humanitarian law, cautioning against the deployment of AI in ways that might increase civilian harm.

The communique called for using AI-driven tools to combat disinformation and fake news while considering the potential for AI itself to generate deceptive content. It emphasised the necessity of strengthening cybersecurity measures by harnessing AI to track and neutralise digital threats efficiently. It stressed the need to equip early-warning systems with AI so officials can anticipate and defuse emerging crises.

Acknowledging the continent’s demographic dynamics, the communique urged AI-driven initiatives to empower youth and women through education, entrepreneurship, and leadership opportunities, seeing inclusivity as a shield against instability. It also urged for data protection and transparency, from national to cross-border levels, arguing that AI’s governance should be harmonised with the protection of civil liberties. And, in a sign of the African Union’s determination to shape rather than merely react to the global AI conversation, the communique demanded the urgent development of a Global Compact on Artificial Intelligence while calling on the Commission to expedite a Common African Position on AI’s impact on peace, security, democracy, and development.

As if to follow through on these directives, the African Union Executive Council adopted the AU Strategy on Artificial Intelligence at its 45th Ordinary Session in Accra, Ghana. The strategy aims to extract the benefits of AI for African nations by encouraging capability-building, investment, and collaboration across the public and private sectors. At the same time, it endeavours to curb AI risks through ethical supervision and regulatory vigilance. By ensuring that AI deployment aligns with human rights and democratic values, the strategy aspires to position Africa not as a passive recipient of external technologies but as an active participant in global tech governance.

The new framework urges collaboration between African governments and their regional and international partners, including the United Nations and private-sector firms, to define principles for AI usage in conflict zones. These efforts acknowledge that AI crosses national boundaries too easily for any single country to handle alone. The strategy portrays Africa’s voice in global AI debates as essential to ensuring that the continent’s historical, social, and material contexts factor into the design of AI standards.

Yet, no document, however thorough, can single-handedly address the disparities in infrastructure and digital capacity that shape AI adoption across Africa. While nations such as South Africa, Kenya, Rwanda, and Nigeria have moved rapidly to establish AI governance frameworks, many African countries face severe technological shortfalls, from intermittent electricity supply to limited internet connectivity. Without adequate resources, these states find themselves unable to integrate AI in early-warning systems or effectively combat AI-fueled disinformation. That gap threatens to widen the gulf between relatively technologically advanced nations and those on the margins. As a result, AI’s potential for good—from peacekeeping to public service delivery—may remain confined to better-resourced corners of the continent.

Nevertheless, a layered approach could address these risks.

The African Union’s Political Affairs, Peace & Security Department, working with the Department of Infrastructure & Energy, has been tasked with establishing a multidisciplinary advisory group on AI and governance. That group will offer proposals for continental AI governance in civilian and military domains and then report every six months to the Peace & Security Council. African leaders can also ground AI usage in well-established norms by tying AI regulations to existing international human rights standards. Africa’s position in the upcoming United Nations Summit of the Future, the forum where a Global Compact on Artificial Intelligence might emerge, could further shape how responsibly AI tools are developed and deployed worldwide.

Even if these steps are implemented efficiently, vigilance remains crucial. AI’s capacity to automate decisions raises profound questions about sovereignty, human agency, and accountability.

If an autonomous system makes a mistake in a battlefield context, mistakenly designating a civilian convoy as hostile, for example, who is responsible for that?

Local communities, civil society organisations, and technology experts should remain engaged in ongoing debates, pushing for transparency in how AI is procured and deployed. Ideally, that engagement would help keep AI from becoming merely another tool that powerful interests use to consolidate power at the expense of the vulnerable.

PUBLISHED ON

Jan 25,2025 [ VOL

25 , NO

1291]

My Opinion | 131297 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 127648 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 125627 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 123265 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jun 14 , 2025

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars...

Jun 7 , 2025

Few promises shine brighter in Addis Abeba than the pledge of a roof for every family...

May 31 , 2025

It is seldom flattering to be bracketed with North Korea and Myanmar. Ironically, Eth...

Jun 21 , 2025

In a landmark move to promote gender equity in the banking industry, the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) has released its inaugural Gender F...

Jun 21 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Officials of the Ministry of Urban & Infrastructure have tabled a draft regulation they believe will...

Jun 21 , 2025 . By AMANUEL BEKELE

A sudden ban on the importation of semi-knockdown and completely knockdown kits for gasoline-powered vehi...

Jun 21 , 2025 . By RUTH BERHANU

Mufariat Kamil, minister of Labour & Skills (MoLS), is rewriting the rules on overseas work, hoping t...