Fortune News | Aug 16,2020

The irony could not have been lost on Abel, in his late 20s, whenever he goes around the National Theater, on Gambia St., searching for forex dealers. Less than a kilometre is the headquarters of the central bank, a federal institution with a firm and historic grip on the allocations of foreign exchange. The neighbourhood is a hub for the foreign currency market parallel to the official. The head office of the Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (CBE), the state-owned bank with the largest source of forex for the country's external trade, is not too distant away.

It was not his first time looking for a dealer on the parallel (black) market; it has been a routine every couple of weeks or months. Abel, who requested his last name be withheld, was there last week, hunting for a better deal to exchange for 200 dollars he had earned from a part-time job at an international organisation the previous week. It has been three years since he stopped using formal channels to exchange foreign currency.

Abel often visits dealers around Tewodros Square, further up on Churchill Avenue. Married last year, he covers a good portion of his expenditures through his dealings on the parallel market.

Despite his long history with the dealers, he was in for a pleasant surprise last week. Abel found that a dollar had exchanged for more than 100 Br – over 10 Br more than the previous rates quoted. He wanted to capitalise on the windfall, bargaining with several dealers to get more for his dollars. Some were offering 17 Br higher than their peers.

The spike in the exchange rate – at some point more than double the official rate offered at commercial banks – is unprecedented.

A dealer around the National Theatre transacts up to 2,000 dollars a day. He has seen demand for forex surge over the past two months. He observed that those looking to do business would rather deal with him and his peers than wait months or even years to obtain forex permits from commercial banks.

Other regulars include foreign nationals and employees of international organisations, who receive their pay in foreign currencies and withdraw a portion of it in cash. Members of the Diaspora are also profitable customers, preferring the parallel market to formal remittance through banking channels. However, the central bank reported nearly 5.3 billion dollars in formal remittances last year.

Although the reported figure is the highest on record, those in the banking industry observe not many customers choose formal channels.

Less than 10 customers have visited a Dashen Bank branch in the area to collect remittances over the past two weeks. It was supposed to be peak season for remittances with the successive New Year and Mesqel holidays. The branch manager, who requested anonymity, would have seen fivefold customers come in during this season.

Forex exchgange window at one of the branches of Nib Bank.

It is a piece of the larger picture showing a trend of declining remittances channelled through the banks. This year, it has dropped by four percent at Berhan Bank. Dashen Bank rewards clients 50 Br in mobile credit for every 100 dollars exchanged.

However, the Branch Manager says incentives could do little to compete with the parallel market's rate.

Commercial banks like Dashen and Berhan have long partnered with traditional remittance services, such as Western Union, charging 15pc commission for a transaction. Despite the hype, the emergence of domestic remittance channels has done little to encourage the use of formal channels.

Knee-jerk responses by the central bank have not helped either. Earlier this year, regulators ordered CashGo, a domestic digital remittance platform partnered with the Bank of Abyssinia, to suspend operations while they assess the platform's legality and verify the absence of third-party involvement in its transactions. The suspension was reversed a few months afterwards.

According to Tewedros Shiferaw, co-founder of CashGo, the high commission fees imposed on transactions discouraged people from using traditional remittance vehicles. CashGo has registered 50,000 users and facilitated transactions valued at six million dollars thus far.

Tewodros and his partners plan to integrate with other gateways and link with over a dozen more commercial banks.

But economic pundits do not see the parallel market operating in isolation from the active agents of the officials market. They see the banks and employees active in the parallel foreign exchange market. Bankers advise clients not to wait for approvals for letters of credit (LCs), which could take years to arrive; they lead them to other alternatives, according to Alemayehu Geda, a professor of economics lecturing at the Addis Abeba University and an accomplished researcher on inflation and foreign exchange.

Alemayehu alleges bankers act as intermediaries in informal dealings in exchange for a margin. He accuses some in the industry of buying forex to shield themselves from inflation.

The forex shortage is as much a worry for importers as it is for banks. Over the last few years, the crippling forex crunch has been their most pressing problem. Those in manufacturing, agriculture, and construction have not been spared either. The federal government and regulators at the central bank have attempted to address the issues, but little has come from the efforts.

A directive issued by the central bank a year ago introduced a hierarchy for allocating foreign currency to businesses. Pharmaceuticals, inputs for edible oil plants, and petroleum products comprised the top category. Agriculture and manufacturing follow, with capital goods and motor oil in the final category.

Owned by Chinese investors, Sansheng Pharmaceutical Plc began operations four years ago in Dukem Eastern Industrial Zone after erecting a plant on a 160,000sqm plot. It employed 350 workers until recently. The workers, barring management members, were on leave three months ago. The factory could not operate due to currency shortages.

"Workers are still on leave," said Yared Hirpo, deputy general manager. "The issue hasn't been addressed yet."

Sansheng imports raw materials primarily from China and India to produce up to five billion tablets and capsules and 10 million doses of infusion drugs annually. It requires up to seven million dollars a year to keep production uninterrupted.

Manufacturers like Sansheng have trouble accessing forex from commercial banks despite holding priority status from the central bank.

According to a senior manager at one of the oldest private banks, it is not unusual to see manufacturers with priority access to forex waiting for more than two years to open letters of credit.

Sansheng is still waiting to secure three million dollars in letters of credit from the CBE. A week ago, the company resumed operations temporarily after obtaining spare parts and raw materials that suffice for close to a month of production. Sansheng's overhead and payroll expenses add up to 20 million Br a month.

Like many others, it is almost challenging for the pharmaceutical industry to earn foreign currency through exports. International buyers are rare to come by.

The state-owned Ethiopian Pharmaceuticals Supply Agency is the largest buyer in the market. First established in 1947, the Agency distributes over 1,000 types of medicines and medical equipment to more than 5,000 public health institutions. Local manufacturers supply around 10pc of the Agency's demand. It spent 17 billion Br on imported pharmaceuticals last year.

Banks' lack of forex and long waiting lists have pushed importers to turn to parallel markets to meet their needs. They buy forex at higher costs, which they eventually compensate for by inflating the price of their imported goods. The practice is often pointed to as one of the causes of the high inflation imported into the domestic economy.

In contrast, exporters ship out commodities at lower prices than international rates to get their hands on foreign currency, which, more often than not, goes towards parallel import activities.

The government is no less exposed to the forex problem.

Foreign currency reserves are at their lowest in decades, sufficient to cover nearly one month of imports. It is a pressing issue for federal authorities whose attention and focus are gripped by an expensive civil war, declining external loans and grants and a widening budget deficit. From the beginning of the year, a central bank directive compelling exporters to surrender 70pc of their foreign currency earnings has not done much good. Neither have record-high export revenues of 4.1 billion dollars last year made much of a dent; especially when import bills ballooned to four times as much.

Experts observe that recently introduced franco valuta privileges have contributed to the increasing demand for forex. The Ministry of Finance allowed the import of wheat, sugar, baby formula, edible oil and rice through franco valuta a year ago. The central bank was mandated to approve the origin of the foreign currency for these imports.

In April this year, the Ministry announced that the Customs Commission could approve franco valuta imports. These have led to a surge in demand from importers, pushing parallel exchange rates up and flattening the authorities' hopes that the privileges would help tame inflation.

It is a grim situation, likely to grow even more alarming unless policymakers figure out a way to bridge the gap between official and parallel exchange rates. Alemayehu urged them to set higher official exchange rates to encourage formal remittances, and close the gap with the parallel market.

PUBLISHED ON

Oct 01,2022 [ VOL

23 , NO

1170]

Fortune News | Aug 16,2020

View From Arada | Aug 12,2023

Commentaries | Jul 05,2025

Fortune News | Aug 01,2020

Radar | Feb 13,2021

Radar | Jul 27,2025

Fortune News | Jul 13,2020

Radar | May 23,2021

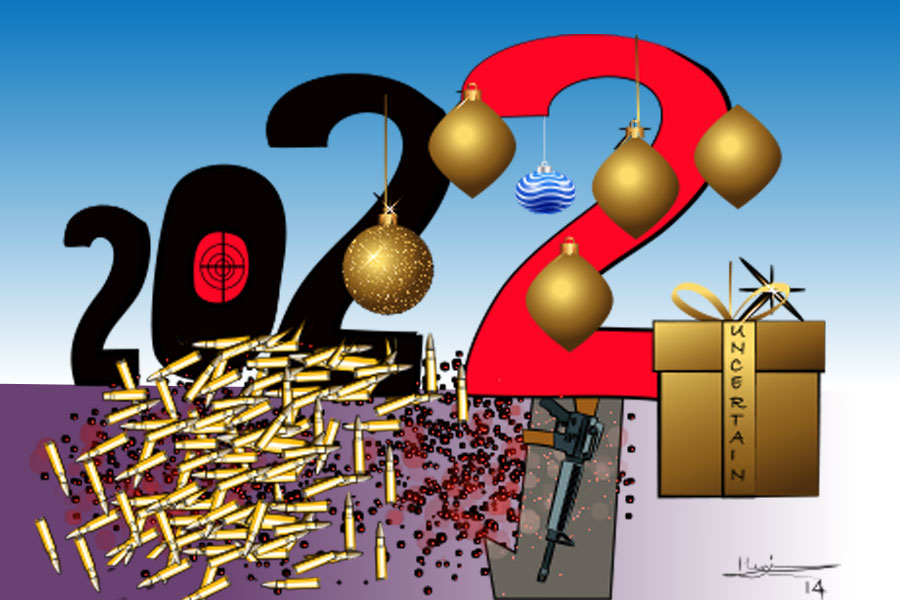

Editorial | Jan 01,2022

Agenda | Jan 23,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...

Sep 20 , 2025

Getachew Reda's return to the national stage was always going to stir attention. Once...

Sep 13 , 2025

At its launch in Nairobi two years ago, the Africa Climate Summit was billed as the f...