Jan 22 , 2022.

The relationship between fuel price shocks and politics needs no introduction. As a fundamental source of energy that powers modern civilisation, its effect on net importers of oil goes beyond macroeconomics. A paper the World Bank released two years ago puts a number on this relationship. Using a dataset of 207 national elections in 50 oil-importing countries, it finds that a percentage point increase in the crude oil index reduces an incumbents` prospect for re-election by about six percent.

Imagine then what a doubling of prices since the release of this report would do. Add to this a country already under intense political uncertainty, fractured polity and without a history of solid constitutional institutions. There is more than losses at the electoral front for an incumbent at stake. Neither does it take much imagining. Recalling how Ethiopia`s political instability in the mid-1970s climaxed with a revolution that ousted an ancient Imperial system after fuel prices had gone up is sufficient.

With the global price of crude oil at over 80 dollars, Lorenzo Te`azaz Street has a headache it needs to deal with much earlier than anticipated. To its credit, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed`s (PhD) administration intended to deal with subsidies that were never economically sustainable but have been kicked down the road by subsequent administrations. Even before its diplomatic fallout with development partners over the current civil war and funding dried up, it had been phasing out subsidies on sugar and electricity.

It needs to concentrate its efforts on fuel prices.

The share of fuel comprised 12pc of Ethiopia`s merchandise imports two years ago. Compared to double this size in 1998 (or a decade later), recent trends were not historic high. It was even lower than the average for Sub-saharan Africa. Nonetheless, the cost of the subsidies to taxpayers is mounting.

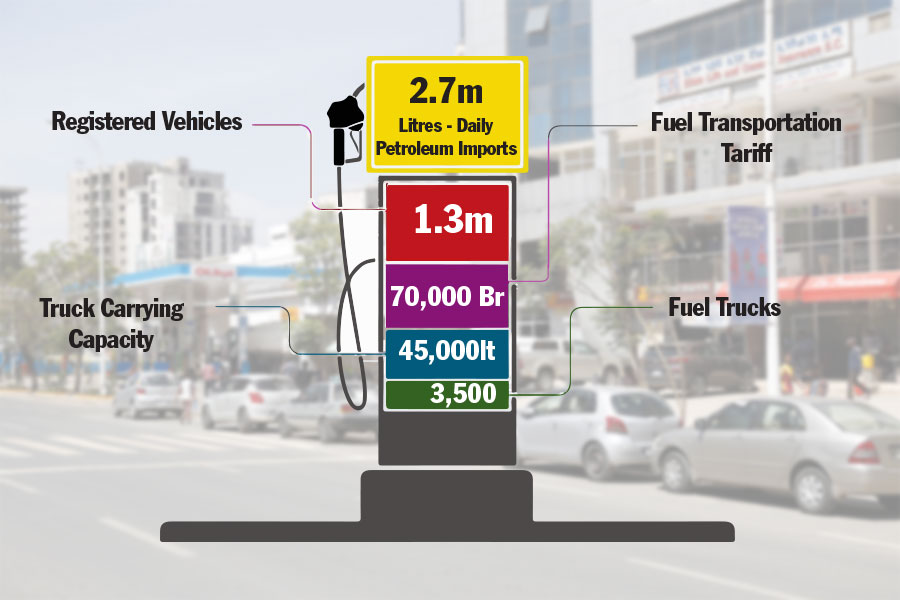

For an economy that absorbs 126 billion Br in a budget deficit, close to 50 billion Br pays for fuel subsidies. The federal agency established to absorb shocks, the Fuel Subsidisation Fund, spent over 82 billion Br to keep prices at pumping stations not to hit 60 Br a litre. The volume of fuel imported hovering at four billion tonnes, the import bill (over 2.6 billion dollars) is going up by a yearly average of 15pc.

The urgency of the matter is a consequence of domestic and exogenous factors. On the former, two years of COVID-19 and over a year of a tragic civil war have left foreign currency reserves alarmingly low. This is complicated by a global inflationary pressure that will likely lead to the upward re-adjustment of interest rates, especially in the United States and Europe. The subsequent impact will be a stronger euro and dollar, making debt repayment for countries such as Ethiopia that have their debts pegged to the Dollar more burdensome on forex reserves.

Domestically, the alternative is increasingly becoming deficit financing through borrowing from the central bank, which is inflationary and can cripple the economy. On the external front, the fuel price in the global market is surging rapidly. It may hit 100 dollars this year. It would be unsustainable for diesel to retail at around 31 Br, costing less than it currently does in major oil exporters such as Russia and the Emirates. The average global price of diesel is presently nearly twice the amount drivers are asked to pay at gas stations in Ethiopia.

The question then is not whether the government can and should remove subsidies. It may not be able, but it has little choice. The burden on the balance of payments and the budget deficit is too heavy to continue to carry. A pragmatic consideration should be how fast and through what process this burden eased from creating a macroeconomic imbalance.

Necessity is the mother of invention, so they say. Some experimenting would have to take place to settle on a suitable alternative to subsidies.

Policymakers begin to see dual pricing as an obvious alternative. In an ideal world, it could work. Priority areas such as public transport, long-haul trucking and manufacturing would get fuel at subsidised prices. Vehicle owners can pay the real price - figuratively and literally - for their higher per capita energy consumption.

If it were so straightforward, every country would be doing it. Double pricing presents the same problem that the government already complains about of cross-border illicit fuel trade. Prices in Djibouti and Kenya are much higher, incentivising contraband trade from highly subsidised Ethiopia to countries that follow market realities. Double pricing will create the same headache but at far lower risk since there are no borders to cross.

International experience will be helpful, though. The regime of double pricing may have been implemented with modest success in countries such as India and Rwanda. However, it does not have a good record, for it provides too much of an incentive for an informal market to emerge. Leakage will be high, and shortages will be even more persistent. Monitoring and enforcement could be increased in countries with better administrative capacity. The Philippines has demonstrated its ability to have such regulatory capability, making the target group narrow.

This should be straightforward in Ethiopia. Households and organisations using private vehicles are concentrated in Addis Abeba. With around half of the 1.3 million vehicles registered are in the capital, the subsidies have ironically been used to subsidise the better-off in society. This should be a factor encouraging policymakers to keep subsidies to public transport operators and long haul truckers. An exception could also be made to manufacturers that use oil derivatives as an alternative to an unreliable power supply.

A combination of digitised processes and a law enforcement apparatus not distracted by war could successfully contain the misuse and abuse of selective subsidies.

Even then, leakage and shortages will be too prohibitive to manage for an extended period. International experience shows that a dual pricing system can only provide a soft landing from the phasing out of fuel subsidies. Extending it longer than its purpose is bound to create the same problems subsidies cause once they are entrenched. Short-term is what subsidies should have been. A policy that respects market realities should utilise subsidies temporarily in times of high crude oil prices, like now, until they stabilise while setting them at least equal to the regional average.

Double pricing will also be most useful as a stabilising tool. The administration needs to map out a transitional period where fuel prices are phased out while a dual pricing system is implemented. The most considerable burden would be on small-scale produces that use fuel for either manufacturing or transport and low-income households. Tax breaks and cash transfers could help carry them over in the transition phase.

Ultimately, the subsidies will have to go. They can be considered for stabilising the retail market when global crude oil prices are in a temper tantrum. Until that happens, the dual pricing system is the best alternative. It will be a flawed but unavoidable experiment to carry out.

PUBLISHED ON

Jan 22,2022 [ VOL

22 , NO

1134]

Verbatim | Aug 13,2022

Commentaries | Jul 29,2023

Fortune News | Nov 24,2024

Radar | Nov 20,2023

Radar | Aug 03,2025

Fortune News | Feb 12,2022

View From Arada | Aug 12,2023

Sunday with Eden | Mar 13,2021

Radar | Apr 09,2022

Fortune News | Jan 22,2022

Photo Gallery | 176541 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 166754 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 157286 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 136920 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

In a sweeping reform that upends nearly a decade of uniform health insurance contribu...

A bill that could transform the nutritional state sits in a limbo, even as the countr...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A long-planned directive to curb carbon emissions from fossil-fuel-powered vehicles h...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Transaction advisors working with companies that hold over a quarter of a billion Bir...