Agenda | Jan 30,2021

Jan 9 , 2021

By Christian Tesfaye

In a way, when Alfred Binet, French psychologist, created what would eventually morph into the intelligence quotient (IQ) test, he was trying to create order.

He was commissioned to do a study by the French government, which wanted to have a way of identifying children that would do good in school from those that needed more hands-on help.

Binet was a scientist ahead of his time. He did create the test but warned against generalising. The concept of intelligence is complicated. One cannot merely use a test to make judgments as to a person’s ability. It serves a purpose; it helps identify students unlikely to keep up with a specific curriculum. Through standardisation, it makes it possible to better spend resources – in this case, in education. It helps ensure order.

But it can be misused. It can be utilised to justify Social Darwinism. Society does not lack for cynicism, and sure enough, a piece of knowledge designed to facilitate order was being used to marginalise and dehumanise populations. This was the case when IQs came to be used to explain differences between Whites and Blacks since the latter score lower on average than the former.

However, it was not true – or at least there is as of yet no strong evidence to suggest that some races are more intelligent than others – that Blacks are less intellectually gifted. The playing field is skewed. They are being cheated. For far too long, the IQs tests have been drawn up by people of a particular socioeconomic circumstance that few found it odd to call out that mostly only people of that same group scored higher. It was socially and culturally biased.

The history of IQ tests is just one example of how society, in its attempt to create order, puts in place all of these rules and standards that go on to marginalise and disenfranchise groups.

It is also the case that these methods of standardisation are important if utilised the right away. Let us go back to IQ tests. Primarily, despite the fervor of the early eugenicists, there is nothing to suggest that its early development under Binet in France was anything other than predicated on good intentions.

More to the point is that this method of standardisation has been used positively within society. It is a helpful way of forecasting educational attainment for designing educational policies. As it was pointed out in an episode of popular podcast Radiolab, “Problem Space,” IQ tests were instrumental in exposing the adverse effects of lead poisoning in children and the subsequent banning of lead from most products.

IQ tests cannot measure something as abstract as intelligence but they measure something - at least the ability to solve familiar problems faster.

This suggests that it is not useless and that societies nurture norms, values and even hierarchy with some purpose in mind. They function to allow humanity to order nature – a task that we are perpetually engaged in.

But our perpetual search for order also blinds us to the injustices committed in trying to find it. In the name of serving the higher good, we insist that such standardisations, hierarchies and norms and values cannot be amended. In our lowest points, we even begin to assume that some groups and individuals have a natural place in the world, that they are less useful.

In the interest of avoiding cynicism, we should assume that most people are willing to reconsider their ways and attitudes if they are offered an alternative outlook. This helps us see that society’s impulse for an order is not in itself a bad thing. It comes from a place of good intentions. The problem is the means of arriving at it.

If order, controlling nature, is the end goal, and the standards, norms and hierarchies are normatively positive, then it is clear where the problem lies. It emanates from the inability to see that the way we do certain things is harmful to people outside our socioeconomic group. It makes a case for diversity.

This reasoning should then be the best argument against the claim that a meritocratic system will be hamstrung by the simple act of insisting on diversity. If socioeconomic circumstance informs decision-making, then society can only make the best decisions for its well-being if all of its participants have a fair voice and influence. Meaningful meritocracy can only be created through diversity and order best attained.

PUBLISHED ON

Jan 09,2021 [ VOL

21 , NO

1080]

Agenda | Jan 30,2021

Life Matters | Dec 16,2023

Fortune News | Aug 20,2022

Agenda | Aug 17,2019

View From Arada | Jan 18,2020

Radar | Aug 21,2021

View From Arada | Nov 14,2020

Covid-19 | Jan 30,2021

Fortune News | Jul 21,2024

Featured | Sep 07,2025

Photo Gallery | 150680 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 140942 Views | Apr 26,2019

My Opinion | 134736 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 131310 Views | Aug 21,2021

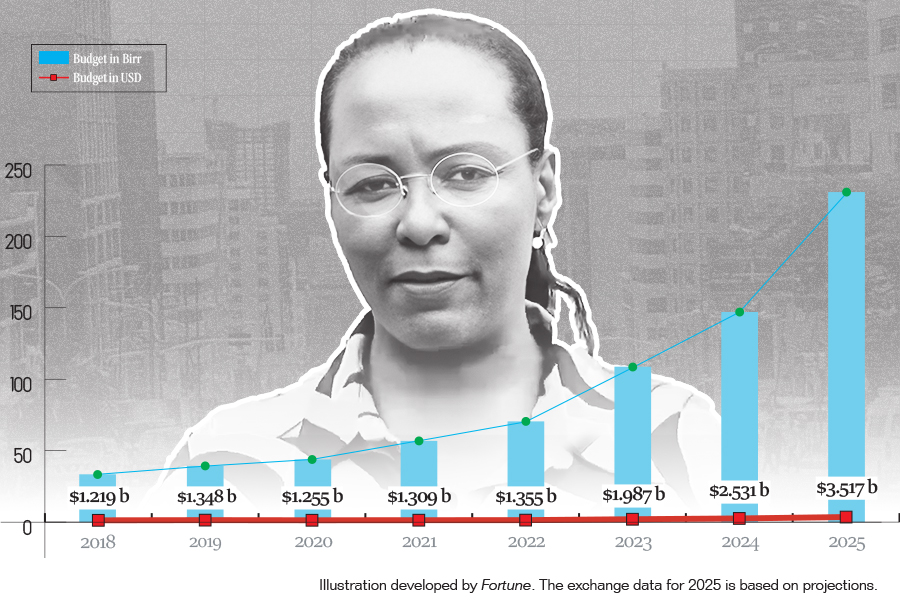

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Sep 6 , 2025

The dawn of a new year is more than a simple turning of the calendar. It is a moment...

Aug 30 , 2025

For Germans, Otto von Bismarck is first remembered as the architect of a unified nati...

Aug 23 , 2025

Banks have a new obsession. After decades chasing deposits and, more recently, digita...

Aug 16 , 2025

A decade ago, a case in the United States (US) jolted Wall Street. An ambulance opera...

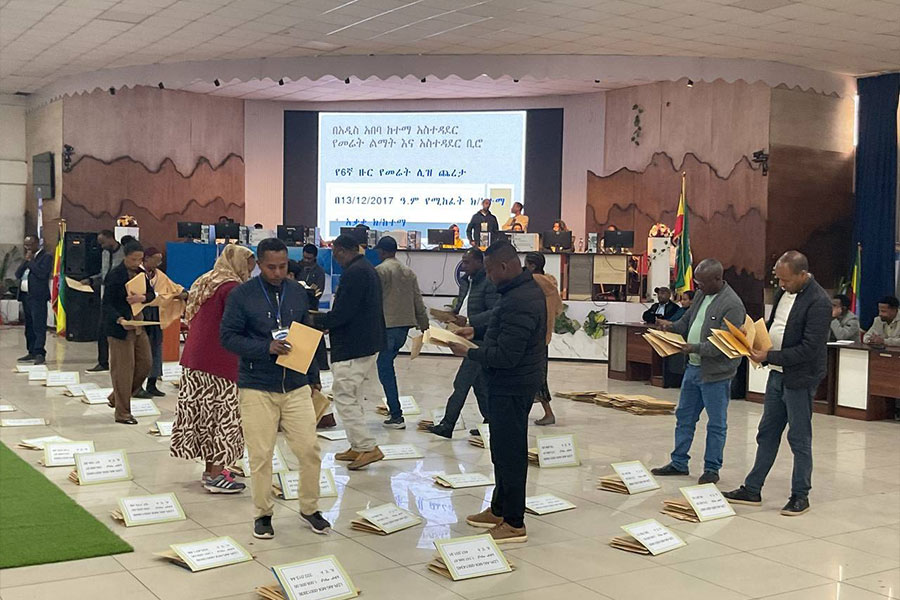

Sep 7 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

Addis Abeba's sixth public land lease auctions after a five-year pause delivered mixe...

Sep 7 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Brook Taye (PhD), the chief executive of the Ethiopian Investment Holdings (EIH), is...

Sep 7 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

For decades, Shemiz Tera in the Addis Ketema District of Atena tera has been a thrivi...

Sep 7 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A dream of affordable homeownership has dissolved into a courtroom showdown for hundr...