Advertorials | Jul 30,2025

Jun 17 , 2020.

It is characteristic of the general climate of confusion the year 2020 has set in Ethiopia and the global stage in general. There is an air of melancholy.

In just a few months, the spirit of the Constitution was afforded as much respect as its intent was devalued. The circumstances were at first ominous.

The National Electoral Board of Ethiopia (NEBE), citing disruptions caused by the Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, decided to postpone the much anticipated national elections, which were slated for August. It was a fateful decision that failed to pass the test of considerable and thoughtful reflections.

But it set off a substantive and rewarding debate on the letter and spirit of the Constitution, with legal scholars reflecting on the possibilities and implications of postponing the elections. No less encouraging was to see the Council of Constitutional Inquiry (CCI) hold a hearing chaired by Chief Justice Meaza Asheanfi, president of the Supreme Court, for legal and constitutional experts to add to the discussion. It was an uplifting exercise of the sort rarely witnessed in the country's political history.

Alas! What followed was a decision that overwhelmingly echoed the positions of the incumbent, effectively extending its hold on power beyond what is allowed in the Constitution and without any attendant limits. It even irked some of the individuals who took part in the scholarly debate, with high hopes of a meaningful outcome.

The decision came on June 10, 2020, when members of the House of Federation approved the recommendations that came from the Council a day earlier. Legislators across federal and regional councils had their terms of office extended until the upcoming elections. The time frame for this was made entirely under the discretion of the executive branch.

Unwittingly, a process stewarded by Chief Justice Meaza granted a legal closure to what is essentially a political deadlock. History will remember her and those legislators who have voted in favour of their decision needlessly.

Members of the House of Federation fully endorsed - with only four votes against - the recommendations from the Chief Justice and her team. There will be elections held nine to 12 months from the time the Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic is declared to pose no threat to public health. This may be three years from now, considering that the consensus among the medical community is that the pandemic could last until 2022, which is also the views of the Centre for Infectious Disease Research & Policy of the University of Minnesota.

If the rippling effects of granting the incumbent an extension of its full power based on a contested deliberative political and constitutional process was not apparent, there have been signs of ill omen over the past week.

Three major opposition parties - the Oromo Federalist Congress, Oromo Liberation Front and the Ogaden National Liberation Front – have warned of an increase in tensions. In the case of the first two, the consequence could be a return to public discontent and possible eruptions of anti-government protests that “could transform into violence,” according to a joint statement they released.

Perhaps the most worrying, if not gravely concerning, development is the deteriorating relationship between the federal government and the Tigray Regional Government.

On the same day Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) took questions from MPs on the economic and political state of the country, mainly about the impact of COVID-19, Keria Ibrahim, speaker of the House of Federation, resigned. She had not even tendered a formal resignation letter to the House when she made this announcement in a press conference. Keria attributed her resignation to what she claimed was “unconstitutional manoeuvring" to extend the national elections.

It is a decision in keeping with the uncompromising position of her party, the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF), on any attempts to extend constitutionally limited terms of office. Having vowed to continue with the elections for the regional council, the TPLF has reiterated in multiple statements that the legitimacy of the current government is unacceptable without a fresh electoral mandate.

It seems a position followed by a resolution by members of the regional state council to hold elections in the Regional State before September this year. They have also directed the regional administration to request that the electoral board carry out the poll on time. The regional administration was told by the Council to prepare an electoral agency to carry out elections should the National Election Board be "unwilling or unable" to do as such.

It is a view in sharp contrast to the administration of Prime Minister Abiy and the chief of the Electoral Board, who believes election management is not a devolved power.

At an impasse, the regional council wrote a letter addressed to the international community to resolve the impending “danger hovering over" the country by leaders it alleges are "working in earnest to institutionalise an autocratic and a one-man dictatorial rule.” Stressing that the incumbent will no longer have a constitutional mandate after October 5, 2020, the regional government, a part of the republic, asked for external actors “not to sit idly by” while the country falls apart.

It is an indication of the grim political state of affairs Ethiopia is setting itself up for. It is perhaps gloomier than the uncertainty of the past two years that have seen communal violence and partisanship that led to the internal displacement of millions and the assassinations of high-level military and regional government officials.

For Kjetil Tronvoll, the Norwegian professor of peace and conflict studies, there has never been for Ethiopia a moment like this where "so clear indications and clear trajectories" with potential for armed conflicts, if left "unmitigated," are evident.

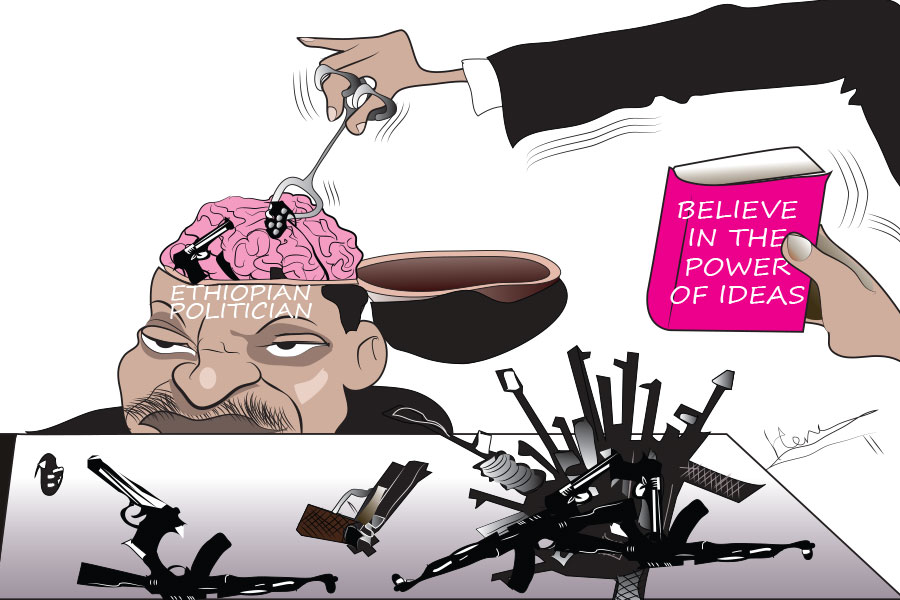

Indeed, a notable development within the Ethiopian state over the past year has been the increasing verticalisation of violence, which portends the confrontations that arise as relationships further sour between the incumbent and the opposition. Distinctive of the transition of power in 2018 was the reconfiguration of the form of violence taking place in the country. The three years of political instability that led to the rise of Abiy Ahmed were mostly anti-government protests, including an assault on the institutions and the businesses that were perceived to be either partisan or supportive of the political power base at the time.

The post-2018 period was attended by an added dimension of horizontal conflicts, as the various political groups attempted to assert their hold in a socio-economically and politically transforming state. Hostilities were decentralised, no longer having a generally singular aim, and usually directed at neighbouring, resource-sharing communities.

Hostilities have once again become verticalised. Over the past year, as the promise of a plural democratic settlement fades away and the incumbent deems certain threats no longer tolerable, confrontations between the opposition and the government have increasingly turned violent. Violent clashes both in the Oromia and Amhara regional states, which have gotten international attention, have begun to taint the overwhelmingly positive opinion the administration has been commanding from the international community.

In a century where even the most localised of military conflicts incur an incalculable loss on human lives, the consequences of organised violence are impossible for the country to recover from for decades to come.

It is hard to believe that conflicting parties would assume violent confrontations are to anyone’s benefit; even for the victor, it will not feel like a victory. But this also may well be a matter of unbridled brinksmanship, an attempt from either side to secure maximum negotiating power.

The risks of miscalculation are nonetheless high, and time is of the essence, that a sequence of events will be unleashed that neither side can control once there is momentum.

Neither will it be an issue that will address itself or find a favourable intervention from external actors. It is also clear that neither party will unilaterally change course and accept demands from the other. The last resort of choice for the federal government and its regional challengers to avert a collision course is to reignite the promise of democratisation.

It can only happen when those in the opposition are convinced that they have a say in the future of the country, something that can only happen when there are checks on the power of the incumbent until the next elections are held. A violent settlement can also only be avoided when the opposition, even in the face of authoritarianism, is determined to exhaust every avenue of peaceful resistance, including civil disobedience.

The alternative is too costly to justify.

PUBLISHED ON

Jun 17,2020 [ VOL

21 , NO

1051]

Advertorials | Jul 30,2025

Editorial | Jun 29,2019

Radar | Sep 08,2019

Agenda | May 31,2020

Radar | Nov 05,2022

Viewpoints | Apr 30,2022

Viewpoints | Apr 11,2020

Radar | Oct 05,2024

Fortune News | Feb 26,2022

Covid-19 | May 01,2021

Photo Gallery | 171767 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 162004 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 151751 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 136319 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 5 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

In Meqelle, a name long associated with industrial grit and regional pride is undergo...

Oct 5 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal government is set to roll out a new "motor vehicle circulation tax" in th...

Oct 5 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

The Bank of Abyssinia is wrestling with the loss of a prime plot of land once leased...

Oct 5 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The Customs Commission has introduced new tariffs on a wide range of imported goods i...