Oct 12 , 2024.

In his inaugural address on October 27, 2024, Taye Atseqesellasie, the fifth president since the 1995 constitution, extolled mutual trust as Ethiopia’s most valuable legacy for future generations. Yet his speech, delivered to a joint session of the two legislative houses, skirted the storm clouds gathering on the horizon — at home and abroad.

Replacing Sahle-Work Zewde after her single term, President Taye focused much of his nearly hour-long address on the economy.

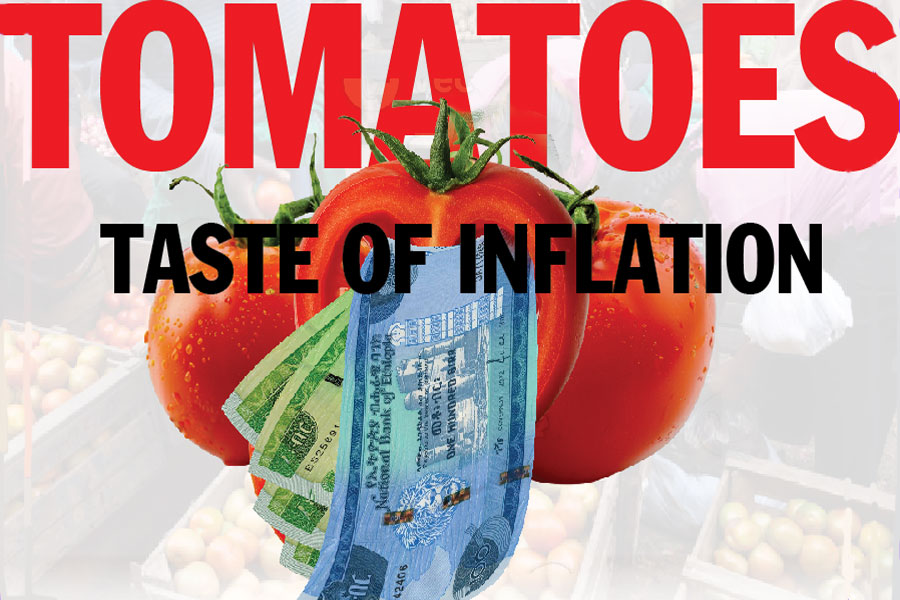

He lauded achievements such as an 8.1pc GDP growth last year; inflation tamed to 17.2pc in August, 27 billion dollars mobilised in foreign exchange, and an agricultural sector growing by 6.9pc, harvesting 700 million quintals of grains. He forecasted economic growth of 8.4pc next year, with federal authorities projecting domestic revenues of 1.5trillion Br (14 billion dollars in last week Central Bank's exchange rate), increasing its tax-to-GDP ratio to 8.3pc, and mobilising 20 billion dollars from exports and foreign direct investment (FDI).

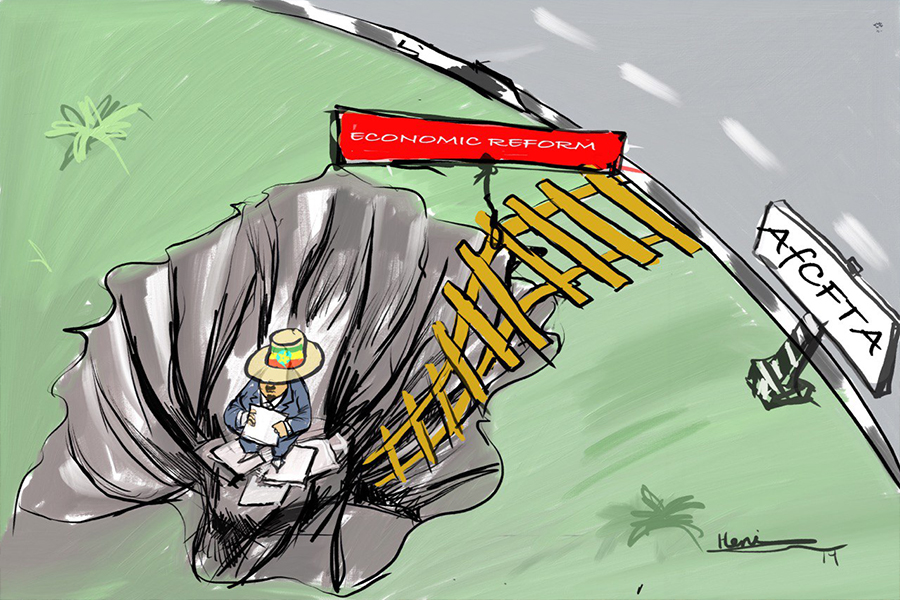

The President asserted that such bullish projections stem from ongoing macroeconomic reforms prioritising a climate-resilient economy, overhauling the construction and finance sectors, formalising the informal services sector, broadening the tax base, introducing new taxes, and modernising public expenditure. President Taye characterised the economy as reaching a "new historical juncture" where policy pragmatism and a market-led trajectory prevail. He declared this is an era of "fiscal and monetary tightening," targeting the control of inflation.

While he spoke of economic progress and future ambitions, he glossed over the pressing security issues that threaten not only Ethiopia but the entire region. His brief mention of the government's determination to reclaim the monopoly of the use of coercive force to restore law and order was insufficient, summing it up in no more than four minutes.

He did, however, praise the progress of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), not merely as a construction project to generate electricity, but as the embodiment of Ethiopians' aspirations and moral fortitude. He told Parliamentarians that the GERD has completed its fifth round of water filling — a source of tension with Egypt — and is 96pc complete, with civil works fully finished.

Yet another source of regional friction looms following Ethiopian leaders' publicly pronounced quest for sea access.

In January, Ethiopia signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with Somaliland, the self-declared but unrecognised breakaway state from Somalia, to lease land for a port or naval base along Somaliland's 20Km coast. In return, Ethiopia agreed to recognise Somaliland's independence, seeing the deal as a strategic coup for a landlocked country of over 100 million people, potentially granting direct access to the Red Sea's vital shipping lanes via the Bab al-Mandeb Strait. It is through maritime corridor an estimated 6.2 million barrels of oil transit daily.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) has been unequivocal, asserting that access to the Red Sea is "our natural right." Since Eritrea's independence in 1993 severed Ethiopia's coastline, over 90pc of its imports and exports have passed through ports in Djibouti, a reliance Abiy is keen to reduce. However, his bold move to disclose his country's desire to recognise Somaliland as a sovereign state has sparked a diplomatic firestorm.

Somalia's President, Hassan S. Mohamud, vehemently rejected the deal, labelling it a "blatant assault" on his country's sovereignty, despite Somaliland exercising functional autonomy for three decades. His government declared the agreement "null and void," insisting Somaliland is an integral part of Somalia, and that any agreements about its territory without federal consent are illegal. Compounding these tensions, Somalia's President met with Egypt's Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi and Eritrea's Isaias Afwerki in Asmara last week, a few days after President Taye described the tensions over the MOU as "needless fever." The three leaders signed a tripartite agreement, evidently aligning against Ethiopia's manoeuvres.

The Horn of Africa appears to be relapsing into the strife of the 1980s. Ethiopia may have inadvertently ignited a regional tinderbox in pursuing its long-held ambition to secure access to the sea. At home, it is besieged by internal conflicts that have escalated alarmingly. Between early February and late May 2024, over 3,117 conflict-related fatalities were recorded, an 85pc increase from the preceding period.

Multiple insurgencies plague the country, with underlying political grievances remaining unaddressed. Without meaningful negotiations for a broader political settlement between the federal government and armed groups in the Amhara and Oromia regional states, asymmetric warfare is bound to continue. All sides seem capable of prolonging military engagements, whether through conventional warfare or guerrilla tactics. The continuation of these conflicts threatens not only Ethiopia's stability but also the fragility of its neighbours.

The National Defence Forces, already stretched thin trying to quell discord within Ethiopia's borders, may find themselves challenged for external engagements with Somalia and its allies. Since the signing of the memorandum, Somalia's leaders have pivoted towards Turkey and Egypt, forging alliances that could alter regional power dynamics. In February, Somalia entered a comprehensive economic and defence agreement with Ankara.

Turkey agreed to rebuild the defunct Somali navy, strengthening Somalia's maritime capabilities along its 3,200Km coastline, the longest in mainland Africa. In return, Turkey secured rights to explore and potentially extract up to 30 billion barrels of undeveloped offshore oil and gas reserves in Somalia's exclusive economic zone.

Not to be outdone, Egypt has ramped up its military cooperation with Somalia. In August, Presidents al-Sisi and Mohamud signed a defence agreement, including Egypt contributing troops to the African Union (AU) mission in Somalia slated for 2025. Reports suggest Egypt has already deployed soldiers to Mogadishu and armed Somalia's army. Viewing Egypt's involvement as akin to Turkey's strategic positioning along the Red Sea corridor would be naive. Egypt is determined to counter Ethiopia's growing regional influence, particularly over the contentious GERD, which it considers an existential threat to its water security.

Understandably, Ethiopia's leaders perceive Egypt's military buildup in Somalia as a direct national security threat. President Taye, while serving as foreign minister in August, issued a stern warning, implicitly cautioning Egypt against destabilising actions in the region. He declared Ethiopia "cannot tolerate" external actors compromising its security.

Somalia's national security adviser, Hussein Moalim, threatened to expel Ethiopian troops participating in the AU mission. If realised, this could create a security vacuum for al-Shabab to exploit, expanding its foothold. Ethiopia's intent to keep its forces in Somalia beyond the AU mission's conclusion, citing national security concerns, merits consideration.

The risk of escalation is real, as international mediation attempts have borne little fruit. Turkey, despite its commitments to both Ethiopia and Somalia, finds its role as an impartial negotiator compromised by its military ties with Somalia and rapprochement with Egypt. The AU and the United Nations (UN) have urged de-escalation, but their calls have yet to translate into meaningful action.

A full-scale conflict between Ethiopia and Somalia, potentially drawing in Egypt and Turkey, would be disastrous. It could destabilise the Bab al-Mandeb Strait, impacting global energy markets. Disruption in a region where an estimated 10pc of the world's oil passes daily cannot be overstated. The consequences of inaction are too grave to ignore.

The international community should recognise that the cost of preventing conflict is far lower than the effort and resources required to end one.

Nearly 64 million people across the Horn of Africa are in dire need of assistance, representing one-fifth of the global total. Ethiopia's descent into deeper turmoil could trigger a humanitarian catastrophe of unprecedented proportions. Hosting over one million refugees and asylum seekers, the country has seen a 30pc uptick in its refugee population.

As Ethiopia stands at a crossroads, its internal turmoils demand attention and resources. Diverting focus to external ambitions without securing internal stability is a perilous risk. Its leaders should weigh the immediate allure of Red Sea access against the long-term costs of regional isolation and conflict. That diplomacy, not brinkmanship, is needed to contain the Horn of Africa's powder keg should have been the message anchoring President Taye's inaugural address.

Undoubtedly, the Horn of Africa is at a delicate juncture. A misstep could plunge the region into chaos, with far-reaching implications beyond its borders. It is incumbent upon Ethiopia's leaders to steer the country away from the precipice, focusing on prudence to resolve disputes and building mutual trust — the very virtue President Taye espoused — as the foundation for enduring peace.

PUBLISHED ON

Oct 12,2024 [ VOL

25 , NO

1276]

Radar | Oct 12,2024

Editorial | Aug 07,2021

Commentaries | Mar 04,2023

Radar | May 18,2019

Radar | May 25,2019

Fortune News | Jul 19,2025

Editorial | Jun 04,2022

Sponsored Contents | Oct 24,2023

Commentaries | Sep 18,2021

Sunday with Eden | Jul 20,2019

Photo Gallery | 174180 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 164405 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 154545 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 136650 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 12 , 2025

Tomato prices in Addis Abeba have surged to unprecedented levels, with retail stands charging between 85 Br and 140 Br a kilo, nearly triple...

Oct 12 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

A sweeping change in the vehicle licensing system has tilted the scales in favour of electric vehicle (EV...

Oct 12 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A simmering dispute between the legal profession and the federal government is nearing a breaking point,...

Oct 12 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A violent storm that ripped through the flower belt of Bishoftu (Debreziet), 45Km east of the capital, in...