View From Arada | Jun 12,2021

Dec 19 , 2018

Eritrea's financial system, antiquated by any modern standards, speaks to the underdevelopment of the country. But the country would do better not to take the path Ethiopia took as it gradually opens up to the world, writes Ambessaw Assegued (assegued@anfilo.com).

What Eritrea Can Learn by Looking Southward

What Eritrea Can Learn by Looking Southward If one is planning to bring along a credit or debit card to use anywhere in Eritrea, forbear the thought!

“We tell our guests to bring hard currency, in cash, when we book their stay,” says the young and graceful receptionist to a guest who presents a foreign debit card to book a stay at the Asmera Palace Hotel in the capital.

“But the exchange window at the airport says that you do accept cards,” he answers.

“You can’t use them anywhere in Eritrea,” responds the manager, who takes over from the receptionist and attends kindly to a visitor who is steadily growing distraught. “It has been three or four years since our credit processor bank in London informed us by email that they would no longer process payments for us.”

There is no escape from this peculiar dilemma that confronts visitors to Eritrea. The country has been thrown into the shadows behind the throbbing universe of global financial transactions.

For nearly a decade, sanctions on Eritrea prohibited transactions for the purchase, sale or supply of goods and services, as reads the United Kingdom’s, and the European Union’s, order that adopted the sanctions.

For the individual visiting Eritrea and for businesses operating in the country there are no financial instruments by which to transact with the outside world. There are no means by which to send or receive cash, issue drafts or money orders, conduct money transfers or use other payment instruments, deposits, credit or letters of credit.

In Asmera, businesses and factories have grounded to a crawl, stifled by lack of input materials and supplies from the other side of the world. Within the country, the banks are all state-owned and cash withdrawals from private or company accounts are restricted to 5,000 Nakfa a month by each depositor.

“That is the monthly salary we pay ourselves from our own accounts,” says a businessman whose business has been closed and whose employees have been laid off for lack of work.

A manager at a chic hotel in Asmera relates the story of how a contingent from one of the international agencies had stayed there during several days of meetings and accumulated charges in excess of 12,000 dollars.

“We were stuck as the bill could not be settled in the usual way by transfer of funds or credit cards.” They tried every which way, he says, “until they found someone on the other side willing to receive the payment in Zurich, then transfer it to a small Ukrainian bank in Kiev that deposited the sum in Dubai, and finally we were able to access the payment in cash.”

Eritrea is a cash economy. Foreign currency up to 10,000 dollars requires no declaration when entering and is traded, quasi-officially, in the open. Even Birr can be traded in Eritrea.

Now that sanctions have been lifted and peace with Ethiopia has been achieved, grains, coffee, sugar, charcoal, fuel, flour, cement and corrugated metal roofing - items that are apparently in short supply - are being trucked into Eritrea across a free border; while electronics, hard currency and gold from the Middle East are ferried without restrictions into Ethiopia.

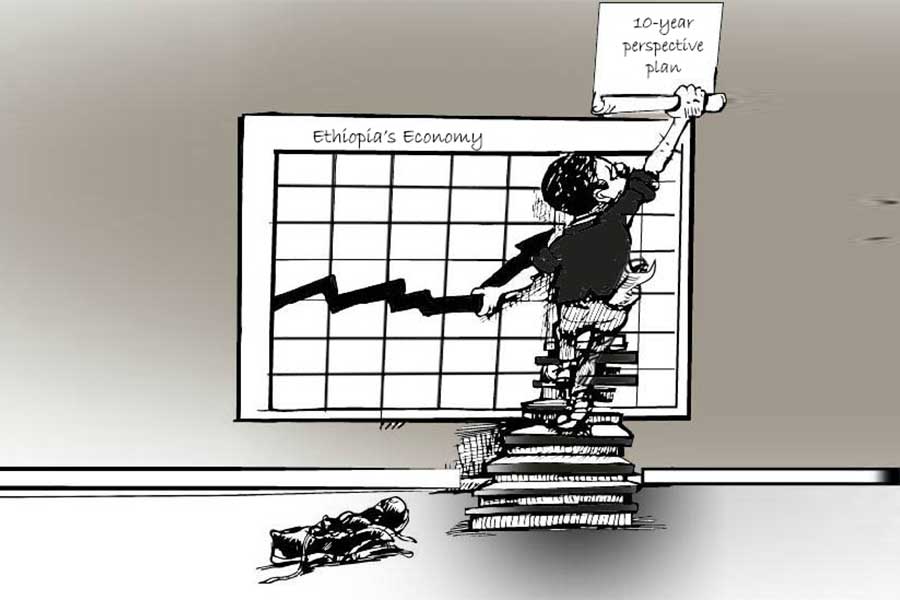

In opening its economy to private banking, foreign investment and the inevitable influx of influences from the West and China, Eritrea will be well advised to look southward and learn a lesson. Ethiopia is the poster child of the debt-ridden and frenzied stampede of development. Ethiopia’s progress, fuelled largely by massive borrowing from China and European largess, has increased income inequality, led to displacement and features a poor if not failed infrastructure.

So far, Eritrea has largely avoided the hazards of the un-finished megaprojects; the consequences of ill-considered infrastructure construction; the unplanned ghettos of concrete tenements; and the unfulfilled promises of grandiose ventures and industrial planning.

But this success in avoiding the pitfalls of hasty development does not excuse Eritrea from the militant and uncompromising pose it took toward the world that led it to be locked out, frozen and left on its own for nearly two decades. The flood of Eritreans that left the country in search of better opportunities when faced with grim prospects is a testament to the folly of the obdurate stand the government took toward governance.

The professional class of Asmera, indeed of Eritrea and their counterparts to the south, need to prod, probe and examine how the two nations can be integrated economically by holding conversations and dialogues.

The golden trance of love and the ensuing honeymoon that we beheld between Ethiopia and Eritrea must inevitably lead to a process that seeks and leads to an enduring relationship and ties between the two.

What is needed urgently and immediately, however, is for both governments to come to grips with the fact that the prevailing free-wheeling activities and unregulated trade across a porous border are unattainable and will set a dangerous precedent of lawlessness on both sides. Cross-border trading and movements should be quickly formalised with customs, taxes and travel regulations.

Meanwhile, the stranded visitor at the Asmera Palace Hotel is rescued by an acquaintance with an infusion of cash, and all the bills are settled amicably. A foreign passport in Eritrea requires that the bearer settle all bills at a hotel in foreign currency. So if one leaves the American Express and MasterCard at home and brings along dollars, Euros or even Saudi riyals, a splendid time can be had.

PUBLISHED ON

Dec 19,2018 [ VOL

19 , NO

973]

View From Arada | Jun 12,2021

Fortune News | Nov 30,2019

Viewpoints | Nov 23,2019

Viewpoints | Oct 07,2023

My Opinion | May 13,2023

Editorial | Dec 26,2020

Viewpoints | Aug 07,2021

Viewpoints | Apr 30,2022

Viewpoints | Jan 04,2020

Fortune News | May 23,2020

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...