Agenda | Nov 04,2023

The strains of city life reach a crescendo for Abel Tesfaye, 29, when a new grocery store near his home around the Yeshi Total area into chaos. The relentless music, blaring from 8:30 PM until midnight, has become an unwelcome lullaby, disrupting his much-needed sleep after an exhaustive work shift as a graphics designer.

"I come home tired and wake up without resting," he told Fortune.

After 21 years of living in the area, Abel and his parents have only recently considered moving due to the nocturnal festivity depriving them of their nightly rest. With appeals to the owners falling on deaf ears, Abel is conflicted on whether or not to report the bar to authorities, even unclear as to whom he should report.

"I can neither rest nor work in my own home," he said.

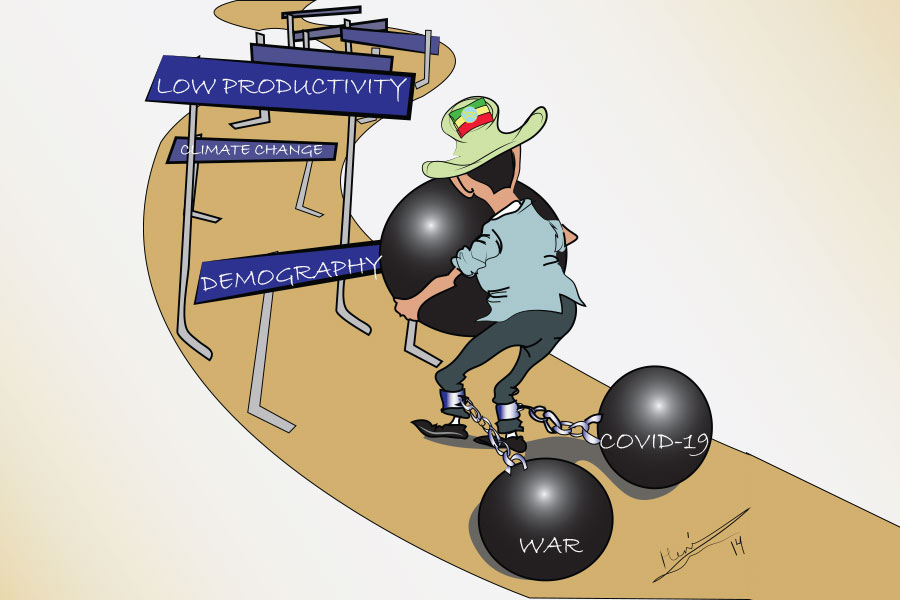

His dilemma reflects the growing concerns of Addis Abeba's citizens as rapid urbanisation unfolds, bringing a mix of towering structures and commercial properties. The city's soaring decibel levels, from street advertisements to car honks, have created a noise pollution epidemic, leaving residents weary.

While noise pollution has long been recognized globally as a significant environmental concern, Ethiopia established its national standard on environmental noise and pollution in 2003. The guidelines set decibel caps for commercial, residential, and industrial areas, aiming to strike a balance between urban development and the well-being of its citizens.

The Environmental Protection Authority developed a noise map with guidelines for a decibel cap that slightly shifts between days and nights for different areas, ranging between 45 at the lowest for residential areas after daybreak and a high of 75 for industrial areas.

According to Girum Gemechu, head of environment compliance & enforcement at the Authority, a poorly planned urban design has crammed residential, commercial, and industrial areas into close quarters. He said religious institutions, dispersed randomly across residential areas, emerge as primary contributors to noise pollution, presenting a challenge for regulators.

"Trying to regulate them is tricky," Girum said, "they get defensive quickly."

The Authority has taken measures on 1,205 individuals over the past six months with 40pc of them being against noise polluters. It has faced limitations in enforcing noise regulations, taking action against only 13pc of the 924 reported businesses over six months, due to resource constraints.

A survey conducted by the Authority identifies Bole District, particularly around the Atlas area, as the most noise-polluted area, with Qirqos and Nifas Silk districts trailing behind with complaints. Lemesa Gudeta, pollution control head at the Authority, attributes much of the problem to the proliferation of bars and grocery stores, citing a lack of proper master planning during the city's expansion.

"Lack of synergy between regulators exacerbated the problem," he said.

Alem Bar, located in the Haile Garment area, becomes a vivid example of a business vying for attention in a bustling market. Manager Belay Ashalew acknowledges the correlation between louder music and increased business. While the bar serves around 100 customers on a good day, it closes when the revelry gets too rowdy.

He rented the place a year ago for a modest monthly rent of 15,000 Br, pinning profitable horizons on the location. Belay claims that a bar requires a relaxed environment with good music, managing to serve around 100 customers on a good day.

"We usually close for the night when customers get loud," he told Fortune.

Addis Abeba presents few restrictions on location, leading to businesses operating close without adequate consideration for noise levels and their impact on neighbours.

Sewnet Ayele, communication director at the Addis Abeba Trade Bureau, highlights the freedom of businesses to choose their preferred locations, with regulatory action taken based on reports from urbanites. He said the Bureau regulates whether or not businesses are subscribing to their stated categories, with crackdowns ensuing after reports come from urbanites.

"A business is free to select a preferred location," said Sewnet.

Noise pollution, however, is not confined to commercial establishments. The blast from car horns in a city with approximately 720,000 cars emerges as a significant contributor, according to studies.

Dereje Worku, traffic monitoring team leader at the Addis Abeba Traffic Management Authority, points to the incessant honking of uncouth drivers as a major source of noise pollution. Although the Authority penalised around 1,029 drivers for loud horns in the past six months, Dereje underscores the need for a broader change in mindset to have a lasting impact.

"There are no standards on traffic noise," he told Fortune. "We regulate out of intuition."

Urban development researcher Tekalign Arifcho (PhD) sheds light on the chaotic soundscape of Addis Abeba, attributing it to the influx of factories and businesses in an unplanned urban area. Despite laws in place, Tekalegn argues for the need to recognise the pernicious impact of noise pollution on the psychological and social fabric. He calls for concerted efforts to improve the city's soundscape and emphasises the importance of synergy among stakeholders.

"There are laws but little implementation," Tekalegn said.

The World Health Organisation recommends limiting daily noise exposure to 70dB and restricting hourly exposure to 85dB to prevent hearing impairment. The impact of noise pollution extends beyond mere inconvenience, raising concerns about its potential contribution to chronic diseases such as hypertension. In Addis Abeba, however, the lack of awareness and enforcement is evident, with outdoor speaker advertisers operating illegally, disturbing the city's landscape.

Residents like Eshetu Jeninu, 42, find themselves constantly battered by the auditory badger. He makes his daily living as an agent handling licensing, payments and permits across several public offices. Eshetu's daily commute across the city exposes him to street advertisements with giant speakers and taxis blaring deafening music from taxis blasting deafening music in low-quality speakers.

"I constantly argue with drivers," he said.

He particularly avoids routes through Mexico and Megenagna areas whenever he can, due to the barrage of street advertisements with giant speakers.

"I can't even think," he told Fortune.

Addis Abeba Construction Permit & Control Authority has started implementing a new set of laws with hopes of monitoring the city's artistic landscape. However, efforts to legalise outdoor speaker advertisers have proven ineffective, registering only 10 companies in the past few months.

Addisu H. Michael, outdoor advertisement director, said that almost all outdoor marketers operate illegally, lacking proper conveying mechanisms. While he acknowledges the disturbed city landscape, Addisu believes there is an impending lack of awareness among society.

It has become common to see huge speakers outside boutiques, clothing shops, and mobile shops, with loud sounds blistering through the speakers' diaphragms. Passers-by seem uneasy with the blistering sounds from clothing shops in the Mexico area where a huge speaker hangs outside and blaring music takes hold of the street.

Rashid Muhadin, 40, the owner, believes the music helps attract customers, though unsure how many are influenced by it. The shop sells trousers, t-shirts, and shoes for a price ranging from 900 Br to 4,000 Br, with an average of 50 people making their way.

"We aren't quite sure if people show up because of it," he said.

PUBLISHED ON

Jan 19,2024 [ VOL

24 , NO

1238]

Agenda | Nov 04,2023

Fortune News | Aug 02,2025

Commentaries | Mar 25,2023

Editorial | Sep 26,2021

My Opinion | May 31,2025

Viewpoints | May 20,2023

In-Picture | Aug 25,2024

Fortune News | May 13,2023

View From Arada | May 31,2025

Radar | Sep 27,2020

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...