Fortune News | Sep 23,2023

The 42-year-old Martha Getachew moved to the Tafo condominium site in Yeka District four months ago.

She bought the house built by the Addis Abeba Housing Corporation for 1.5 million Br from the previous owner and was promised that utilities would be installed by the time she moved in. However, due to incomplete infrastructure, such as unpaved roads, district officials are facing difficulties in providing essential utilities.

As more people moved into the 114 condominium blocks, the attempt to divert power from the contractor's grid for a 500 Br monthly fee proved to be futile.

"It takes hours even to brew coffee," Martha said.

She is weary of the frequent power outages and interrupted running water haunting her residence but could have adapted if the poor sanitation system had not left the neighbourhood smelling like an open latrine.

"The smell becomes unbearable when it rains," Martha told Fortune.

Despite the treacherous conditions, the low price of homes has lured in around 700 people to the Tafo condominium while 3,000 more are getting ready to move in. The project, which began eight years ago, started hosting residents in June, with finishing works seemingly completed last year.

Head of the Yeka District, Abel Assegid, conceded that the lag in infrastructure was a source of frustration for many residents, ascribing it to the poor roads leading up to the housing project.

"Utilities should have been provided by the time 80pc of construction was complete," he said.

The problems are ubiquitous across Addis Abeba as 92pc of residents experience power outages at least four times a week, according to research by the African Cities Research Consortium (ACRC).

It paints Addis Abeba as one of the most challenging to live in from a pool of 12 African cities surveyed, subjecting it to a cocktail of problems concerning transport, health, water and power supply.

Nearly 900,000 residents have access to electricity.

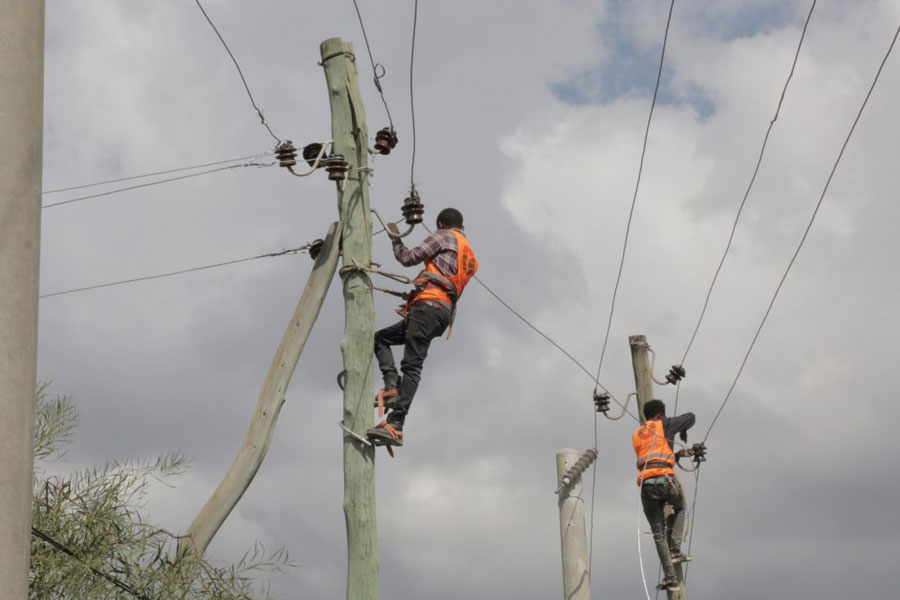

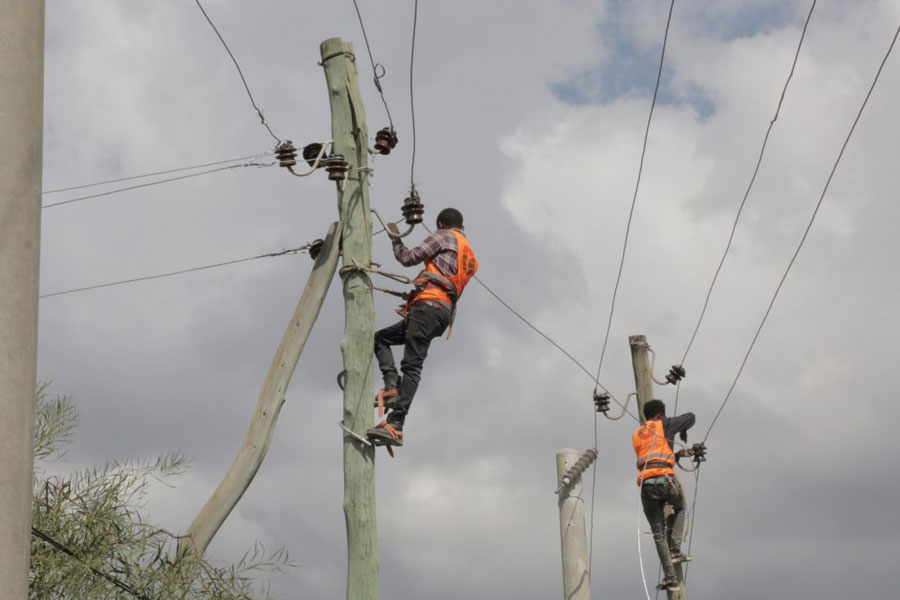

Tegegn Gebregziaber (PhD), a researcher at the Consortium, points towards the deterioration of equipment and the quality of supply as the primary culprits behind the dim aura.

"It is one of the lowest in the world," he told Fortune.

The impact of the aged grid was recognised by the officials.

Communication Manager at the Addis Abeba Electric Utility, Yohannes Gebre, pointed to three grid rehabilitation projects underway as a silver lining for residents while acknowledging that unfinished road segments hamper locations at outskirt locations like Koyefeche, Bulbula and Tafo areas.

"We can't get our trucks to some of the sites," he said.

He said theft, rain and traffic accidents impact continued supply although the grid is accessible to homes in the capital within a five-kilometre radius.

"Connectivity might be an issue," he said, "but access is up to global standards."

However, insiders in the energy sector argue that power politics are driving full access reach narratives while relying on the unattainable 400KV high transmission lines. Real coverage would be less than half and accessibility should be seen through connectivity where transformers 220KV are available for households, according to the experts.

Although Addis Abeba is a political and economic city centre, the lack of transportation has plagued residents' mobility, with a mere 11,800 public transport service providers and poor road infrastructure.

One such daily commuter is Jirtu Tesfa, 45, who dreads the trips to work and back home while longing for alternatives. A 500-meter walk to the bus station, followed by an hour-long queue and a congested route from Gelan to Mekanisa, are highlights of Jirtu's morning.

He said the absence of a railway and congestion is the reason behind his transport woes.

"Transportation is the worst part of my day," Jirtu told Fortune.

The research concurs with his remarks. Motorisation rate in the city stands at 130 vehicles for 1,000 people and a dismal 13pc road density.

Experts in the transport sector observe the city's expansion without properly planning transportation access is worsened by the inappropriate behaviour of service providers.

"That's the reason for worsening road accidents," said Tebarek Lika (PhD), a researcher at Addis Abeba University. He argues 3,136Km of poor road networks and scarce public transport for the capital's underperformance in global transport metrics.

Haile Garment, Bole Bulbula, and Gurd Shola areas are reported as hotspots of traffic accidents with over 212 deaths recorded within six months, according to the Bloomberg Initiative for Global Road Safety.

Tebarek suggests the solution is long and complex, with significant work in redesigning the horizontal expansion towards a more vertical orientation needed as the city’s floor space for a person declines by 40pc if the population doubles while income levels remain constant.

To address the issue, Addis Abeba Transport Bureau is leveraging its 318 million budget for the year and assistance from the World Bank to expand bus terminals, construct parking spots and buy 167 buses.

Natnael Chane, head of transport infrastructure at the Bureau, suggests that uncluttering terminals by managing the supply and demand in rush hours will go a long way in helping the transport problems.

"Though congestion cannot be prevented, it can be managed," he told Fortune.

The streets of Megenagna vividly capture the crowding of the capital, with 25,000 pedestrians huddling along the roads during rush hour to make way to the 14 transit spots tucked close to one another.

The Light Rail Transit (LRT) built eight years ago to accommodate 120,000 passengers daily with 41 locomotives serves a fourth of the amount as the lack of spare parts haunted its function at full capacity.

Aychilum Seleshi, a design expert from Addis Abeba City Roads Administration revealed that plans are underway to shift from highway-centered constructions to ones more fitting for an urban landscape.

"We are revamping the sector with new corridors," he told Fortune.

He said budget constraints and time are the only things limiting the Administration's ambitions to improve the capital's roads. Utilizing an 11.6 billion Br budget for the year, Aychilum reveals plans to enhance junctions, squares and interchanges by connecting roads and tunnels in the capital.

Addis Abeba's unsavoury living conditions are further worsened by the poor health coverage, which stands at 76pc due to a shortage of medical supplies and staff.

While the Community Based Health Insurance (CBHI) scheme provides subsidised coverage to nearly two million residents, the increment in premium prices has raised concerns. Payments have doubled from 500 Br for a person and tripled to 750 Br for household members above 18 years.

Despite the capital's health bureau expanding to six public hospitals and currently constructing new ones alongside 98 health centres, access has been limited. Health economists such as Getasew Amare point to poor financial mobilisation and meagre attention to the sector as driving the surge in costs of medical coverage.

"It's well below global standards," he said.

He explains that the health sector demands significant resources and proper utilisation, indicating that a mere 60pc of the allocation is appropriately utilised.

The ACRC study indicated that water access remains a pernicious problem, with 1.7 million residents getting running water twice a week. The Kolfe Qeranio, Gulele, and Addis Ketema districts were cited as areas with major scarcity.

The demand runs around 1.3 million cubic metres daily. Meanwhile, the Addis Abeba Water & Sewage Authority manages to provide nearly 800,000 cubic metres through its 238 underground wells and surface water from the Legedadi, Dire and Gefersa dams.

Communication Director Serkalem Getachew points to the surge in demand as the reason for the two-day shifts across most of the capital. However, she acknowledges that long-term solutions need to be realised with the Authority resorted to digging 12 underground wells where half have passed on to a contractor.

"Shifts are a temporary solution to an expanding population," she told Fortune.

The current secondary sewage line stands at 1,100Km providing access to a mere 34pc of the capital's residents, with the remaining opting for alternative sanitation modalities. Meanwhile, about 80pc of communicable diseases in Ethiopia are transmitted by poor sanitation.

Ezana Amdework (PhD), urban researcher at the ACRC and lecturer of sociology at Addis Abeba University, indicated that one out of five people in the capital do not have access to sanitation.

"Sewage management remains weak," he told Fortune. Ezana emphasised that low-income households and informal settlements are faced with severe health risks with wastes openly flowing to the river, leading to most of the waterborne diseases.

"A tenth of the water supply is contaminated," he told Fortune, further underscoring foods also become contaminated.

Ezana recommends including the private sector in providing decentralised solutions by availing tax incentives. The researcher pointed to the need for formalising squatters and settlers displaced across the capital into proper accommodations.

"There is a serious lack of inner city planning," he emphasised.

With ever-increasing population size, low system delivery and unconventional integrations Addis Abeba remains fragmented and inadequate to provide basic utility services to its residents.

PUBLISHED ON

Nov 04,2023 [ VOL

24 , NO

1227]

Fortune News | Sep 23,2023

Viewpoints | Aug 29,2020

Radar | May 08,2021

Fortune News | Jul 18,2021

Fortune News | May 09,2020

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 5 , 2025

Six years ago, Ethiopia was the darling of international liberal commentators. A year...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jun 14 , 2025

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars...