Photo Gallery | 177748 Views | May 06,2019

Mar 9 , 2025.

Five years ago, 11 non-governmental organisations (NGOs), together with 40 allies across Africa, demanded a five-year moratorium on Ethiopia’s use of genetically modified organisms (GMOs). They wanted clear regulations and “proper” public consultations. Their appeal did not materialise. Recently, the federal government granted commercial approval for genetically modified maise and cotton, marking a landmark shift in policy and igniting debate over how best to reconcile new technology with realities on the ground.

The late Prime Minister Meles Zenawi had opposed GMOs, but under his successor, Hailemariam Desalegn, the ban on importing modified seeds was lifted. Hailemariam's leadership may have been under pressure from a mounting food insecurity that impacted tens of millions of people. With over 100 million lives at stake, and for all the unknowns, it was convinced that standing still was not an option.

Agriculture accounts for around 40pc of the GDP and employs three-quarters of the population. Yet, food insecurity remains dire. The World Food Programme (WFP) reported that 20.1 million Ethiopians needed assistance in 2023. Smallholder farmers, who produce 95pc of the country’s agricultural output, endure low yields and scarce access to technology.

Since the days of Hailemariam, the political leadership and successive policymakers are convinced that genetically modified seeds, which can resist pests and drought, are indispensable to boosting productivity and reducing dependence on food aid.

Take the lush farmlands of southern Ethiopia, where farmers have cultivated enset, a banana-like staple, for centuries. More than 20 million people rely on it for daily nourishment. The plan to allow genetically modified versions of enset, maise and cotton raises the question of how developing countries might embrace biotechnology without relinquishing control over their agricultural heritage. Policymakers see GM maise, already covering over two million hectares and feeding nine million people, as crucial in a country where population growth outpaces food production. Research on the subject found that around three million hectares are suitable for cotton, though only a tiny fraction is used, a mismatch they hope GM technology can correct.

They tout data showing that newly approved GM maise yields 60pc more than conventional varieties. They are not short of evidence from across Africa and beyond.

Nigeria’s adoption of TELA maise raised productivity by as much as 10tns a hectare; in South Africa, GM cotton yields jumped by 25pc in some trials, while pesticide use dropped by 60pc. Bangladesh slashed pesticide application on its Bt-brinjal by 80pc. These results make the allure of genetic modification irresistible for a country like Ethiopia, which has struggled to feed a large and growing population. Its contemporary leaders argue that raising yields could save foreign exchange otherwise spent on food imports and free resources for industrial ventures.

Chronic drought and conflict have undermined traditional agriculture, and food imports drain precious foreign exchange. Many see GM seeds as part of a broader push to modernise farming, free up labour for other sectors, and boost exports. Pest-resistant varieties could reduce costs and pave the way for a thriving textile industry in the cotton fields of Afar. Modern seeds alone may not solve everything, but ignoring advances in biotech would only deepen poverty and reliance on handouts.

Allowing GMOs could spur agro-industrial development. Up to 75pc of the population depends on small-scale farming, which is often exposed to the vagaries of erratic rainfall. New seed varieties, along with improved irrigation and extension services, could lift yields and reduce the need for emergency food aid. In Kenya GM cotton improved pest resistance, and in Bangladesh smallholders saved money by cutting pesticide use.

According to the International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications, over 190 million hectares of GM crops are grown worldwide, mostly in countries with stronger institutions. Such gains might also allow Ethiopia to stabilise food supplies and shift more resources into infrastructure, education and healthcare.

Nonetheless, in as much as advocates of GMOs argue that, managed properly and with the proper safeguards, the technology can help smallholders boost incomes, sceptics abound. They fear that corporations will restrict seed-saving practices, pushing farmers into dependency. Many smallholders remain wary of locking themselves into contracts with seed companies, fearing they might later face lawsuits or surging input costs. Anecdotes abound of farmers who sign up for seeds touted as higher-yielding, only to discover debt burdens at the next planting season.

Critics recall Burkina Faso’s abrupt exit from GM cotton in 2016, triggered by declines in quality and premium pricing. Accounts of farmers' debt marred India’s experience with Bt-cotton. In Canada, Monsanto, one of the largest seed companies in the world, faced lawsuits for claiming cross-pollination infringed its patents. Critics worry Ethiopia could face similar dilemmas if agribusiness giants dominate seed supply. They question whether Ethiopia has the regulatory muscle to ensure GMOs do more good than harm. It is in doubt.

Researchers uncovered that the National Biosafety Authority, a federal agency, has limited resources to conduct field trials, monitor gene flow and enforce compliance. The country also lacks sufficient laboratories and trained staff. Building the capacity will require investment, training and political resolve. Money is in short supply. Inspectors, extension agents and customs officers need training to recognise approved seeds, spot illegal imports and inform farmers of their rights. Laboratories should be capable of analysing crops for unauthorised traits.

Ethiopia’s abundant biodiversity compounds the risks. Its ecosystems are the origins of Teff, coffee, safflower and enset. But, environmentalists warn that introducing transgenic material could pollute heirloom crops. Critics remain anxious about corporate intrusion into the seed market. Argentina’s broad adoption of GM soybeans displaced small farmers and led to heavier pesticide use.

Agricultural authorities say they have studied these cautionary tales and pledge to hold corporations liable for harm. They also promise farmers will retain the right to choose between conventional and modified seeds. Even so, questions of whether enforcement will keep pace with rapid change remain to be addressed.

The old demand for a five-year pause on GMOs was meant to allow time for guidelines that protect seed sovereignty and biodiversity. That window has closed. The issue is no longer whether the seeds will be sown, but whether the institutions policing them are up to the task. Failure could lock farmers into debt or erode local crop varieties, while success might help transform a struggling agrarian economy.

Farmers in the highlands of Wolaita or on the plains of Afar will be the first to discover whether the country’s new biotech embrace pays off. If it works as officials hope, Ethiopia could move closer to feeding its expanding population, reducing imports and stimulating industrial growth. But worries remain high that a swift rollout, without rigorous oversight, could compromise crop diversity and hand power to global seed firms.

The harvest of the future will soon reveal whether this biotech gamble has been sown wisely. The authorities promised to keep watching for any sign of unintended consequences. Farmers, meanwhile, face both hope and uncertainty as they contemplate a new chapter.

PUBLISHED ON

Mar 09, 2025 [ VOL

25 , NO

1297]

Photo Gallery | 177748 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 167960 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 158654 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 137004 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

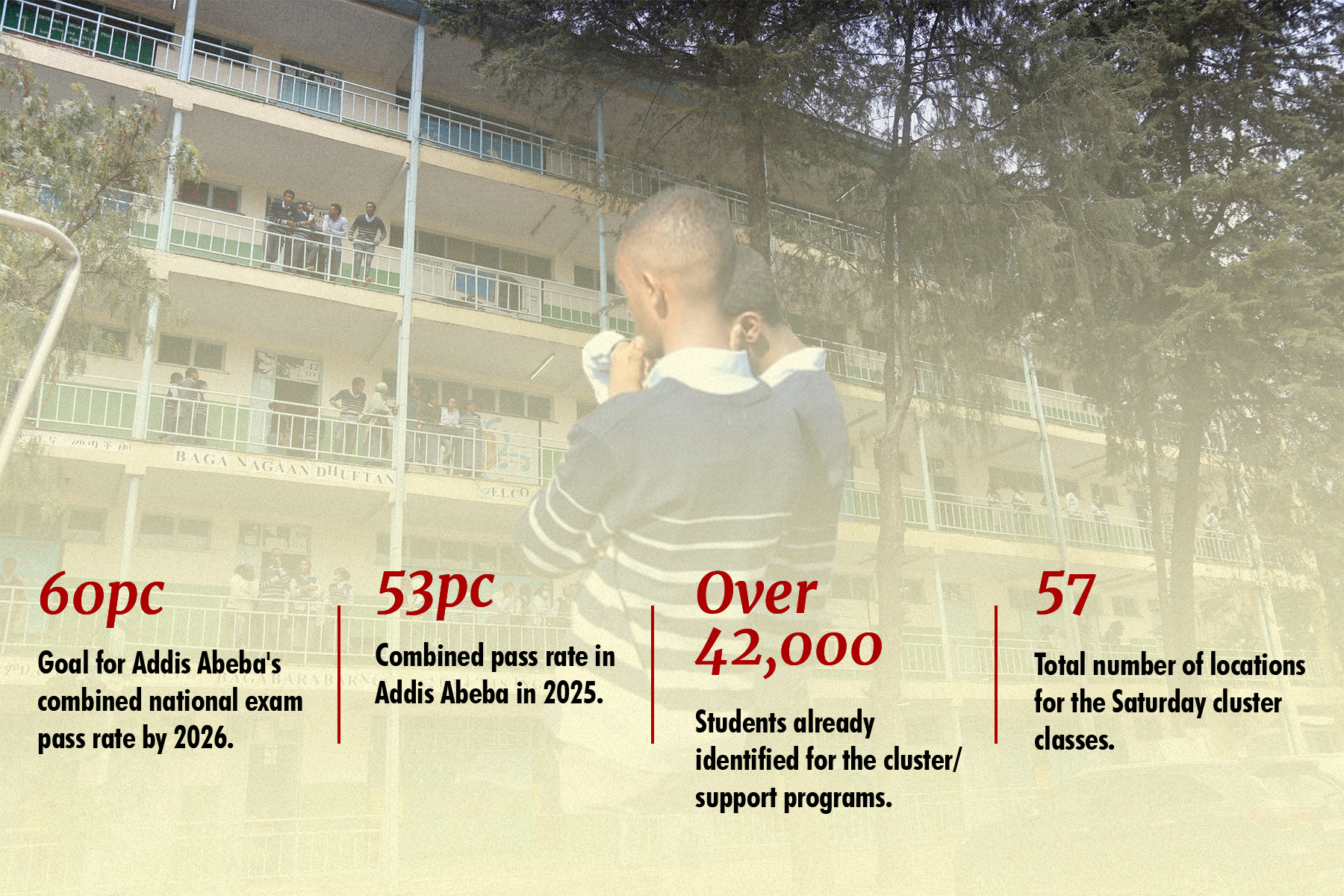

Oct 25 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

Officials of the Addis Abeba's Education Bureau have embarked on an ambitious experim...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The federal government is making a landmark shift in its investment incentive regime...

Oct 27 , 2025

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) is preparing to issue a directive that will funda...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A community of booksellers shadowing the Ethiopian National Theatre has been jolted b...