Fortune News | May 21,2022

Feb 12 , 2022

By Christian Tesfaye

One of the stubborn policies of successive governments in Ethiopia has been an inflexible exchange rate regime. Administrations have protected this area from liberalisation, arguing that this would result in a financial crisis of the sort that began in Asia in 1997. It is not a secret that countries loose with their exchange rates suffered the most back then.

But it would be unfair to characterise flexible exchange rate controls solely based on the infamous Asian crisis, as many left-leaning pundits tend to do. If anything, its failure then shows that no theory or model holds up under every single scenario. The right set of conditions need to align for such a critical part of monetary policy to do good. We need to ask if these conditions are aligning for Ethiopia as well instead of whether flexible exchange rates are helpful.

Mulling this issue, we need to look at one crucial factor that often does not get sufficient consideration concerning exchange rates, inflation (and, subsequently, economic output). Sure, foreign currency reserves are most directly concerned. But a government does not keep a healthy reserve to maintain a score of some sort. It is to ensure that the domestic currency maintains its value and economic output is on the up and up.

Let us consider lifting exchange rate controls under Ethiopia's current inflationary pressure environment.

What would happen?

An immediate effect would be that the formal and black market rates would equalise. People and businesses with foreign currency would no longer need to take their dollars and euros underground to get better returns in Birr. One point for the proponents of a flexible exchange rate regime.

But this will happen as well. With inflation hovering around 35pc, not many would want to hold Birr except for day-to-day spending. They will attempt to hold a large chunk of their savings in dollars. The demand for foreign currencies will explode while that of the Birr would fall far more than it is already doing under a pegged exchange rate regime.

At this point, the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) will be alarmed and place back exchange rate controls. But let us say that policymakers are determined to see through a flexible exchange rate policy and attempt to save the Birr from depreciation in value through other tools as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) would recommend.

The central bank has lost exchange rates as a monetary policy instrument. Remaining in its toolkit are interest rates and the power of money creation. The latter is only useful to do the opposite, to devalue the Birr more. The economy needs less Birr in circulation so that demand for the currency will pick up once again.

Higher borrowing costs will suck Birr out of the economy, so the central bank will want to raise interest rates. More people will be incentivised to save, decreasing the velocity of money circulation. This also makes borrowing expensive, discouraging credit.

Inflation could be contained but at what cost?

Higher borrowing costs will mean that companies will find taking out loans expensive. The same goes for the federal government, which has increasingly relied upon the sale of treasury bonds to finance its expenditure. Worse still, businesses and households (perhaps even the federal government) that need to roll over debt (taking out a new loan to paay back an old debt) will be caught in a firestorm. More companies may go bankrupt as they fail to pay back their debts, leading to rising NPLs and threatening bank failure. In the end, the economy may very well shrink.

Inflation may eventually be brought back down to acceptable levels that allow the central bank to lower interest rates, but probably only after years of economic contraction and devastating unemployment. The price will be too high. It may not even be worth it. Poland, for instance, has historically had persistent double-digit inflation, but it also had robust GDP growth. Poland would not be the East European development miracle of today had it sacrificed economic growth in the name of single-digit inflation. It was able to get past its inflationary events without bulldozing its economy because it did not dare to float its currency and use exchange rates as monetary policy instruments until the turn of the century.

When should Ethiopia lift exchange rate controls?

Only when the economy is not prone to such high inflation as we now have at 35pc. There are fundamental challenges that will, and should, push further away exchange rate liberalisation so economic output is not devastated. This includes the ongoing phasing out of subsidies, especially on fuel, that will continue to exert upward pressure on the rise in the cost of goods and services. The other is supply constraints, especially on food, as in the drought conditions in the east and southeastern parts of the country.

Whenever inflation is pushed upwards, the Birr will risk losing its value. The central bank does not worry too much about this because it controls exchange rates. If it gives up this power, and people can freely rush to dump Birr for the dollar, it will be forced to respond in a manner that harms economic growth.

Turkey also faces this dilemma. Annual inflation there is 49pc, the highest in two decades. Everybody talks about the pressure the Lira is under as it loses its value but the only prescription economists are suggesting is increasing interest rates. This is because the only thing Turkey’s central bank can do is tweak interest rates. It has long ago lost exchange rates as monetary policy instruments after the Lira was floated. Lowering economic output is the only alternative remaining.

PUBLISHED ON

Feb 12,2022 [ VOL

22 , NO

1137]

Fortune News | May 21,2022

Fortune News | Jan 22,2022

Fortune News | Aug 07,2021

Radar | Sep 10,2021

Viewpoints | Dec 19,2021

Fortune News | Jul 12,2021

Fortune News | May 14,2022

Sponsored Contents | Jun 17,2021

Fineline | Dec 10,2018

Fortune News | Jul 18,2021

Photo Gallery | 179614 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 169809 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 160744 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 137193 Views | Aug 14,2021

Commentaries | Oct 25,2025

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

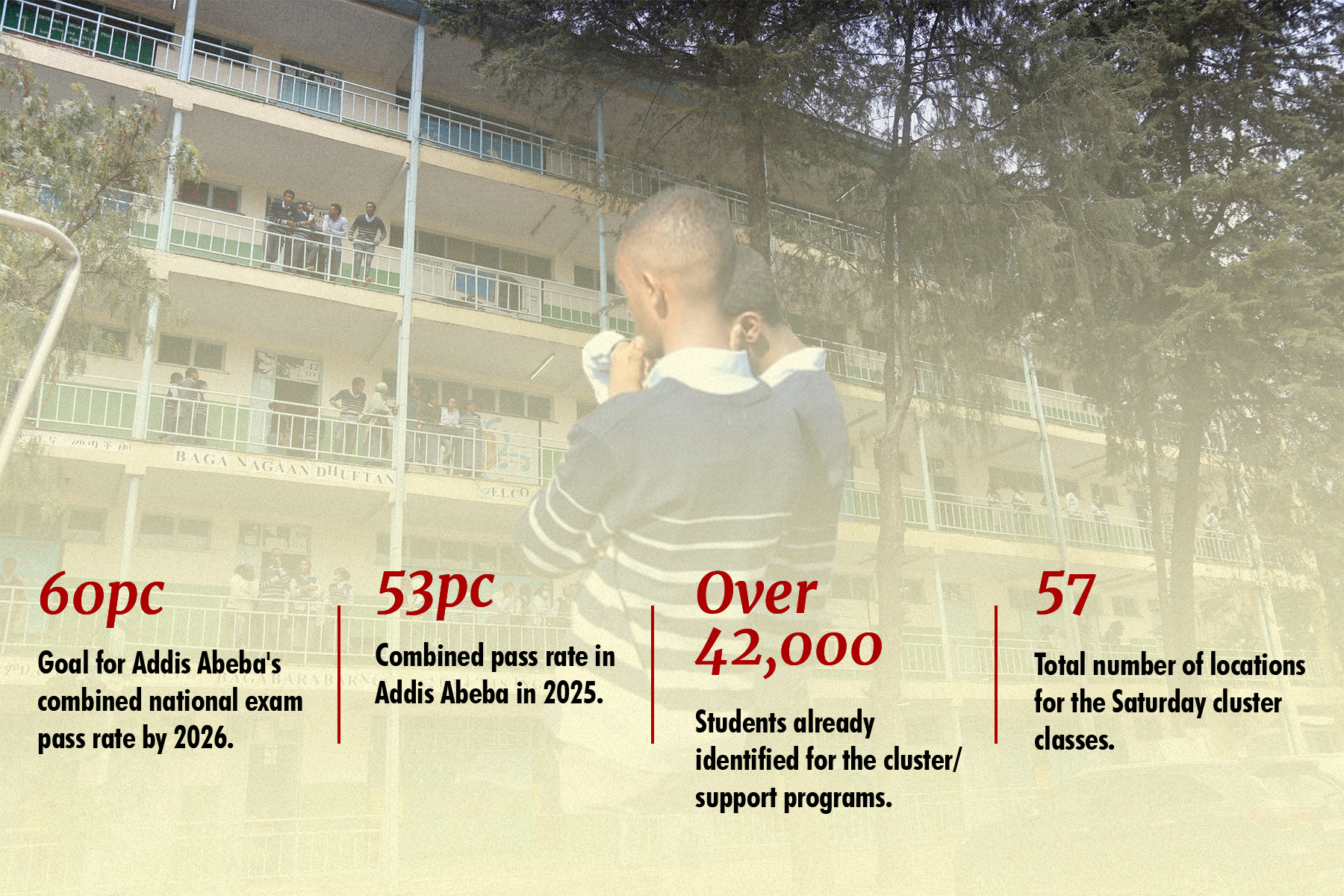

Oct 25 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

Officials of the Addis Abeba's Education Bureau have embarked on an ambitious experim...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The federal government is making a landmark shift in its investment incentive regime...

Oct 29 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) is preparing to issue a directive that will funda...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A community of booksellers shadowing the Ethiopian National Theatre has been jolted b...